In the world of sports, toughness and resiliency are glorified. Athletes who battle through pain and injury are exalted. Worrying about long-term consequences can be taboo, particularly for something seemingly superficial like a hard hit to the head.

Generations of players, coaches and parents have sustained this mindset at all levels of athletics, but research has increasingly uncovered the dangerous and even fatal repercussions of ignoring head injuries. A flood of extensive studies has discovered concussions damage the brain and can lead to an array of possible consequences, especially if an individual suffers multiple concussions in a short period of time while the brain is still healing. The short-term effects can be memory loss, head aches and slowed thinking, but the more extreme effects include depression, personality changes and even death.

“We’re finally taking concussions seriously,” said Dr. Frank Bishop, a neurosurgeon with Kalispell Regional Medical Center’s Neuroscience and Spine Institute. “(In the past) we wanted to ignore it because otherwise that meant maybe sacrificing the sport, but I think we’re really starting to realize the impact is too large to ignore.”

The revelations in research have highlighted a major safety issue looming over contact sports, namely football. A government study released Sept. 5 found retired professional football players are four times more likely to die from brain-related diseases as other men their age.

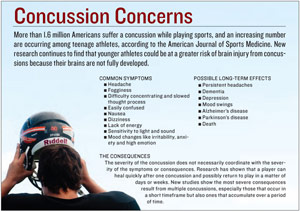

Though the problem is particularly severe at the higher ranks, research has found brain injury affects all levels, including youth and high school athletics. Every year more than 1.6 million Americans suffer a concussion while playing sports, and a growing number of brain injuries are sustained by teenagers, according to a report by the American Journal of Sports Medicine.

Research suggests that younger athletes may be at greater risk of cognitive damage from concussions because their brains are not fully developed. The two scenarios that doctors and others are trying to prevent are multiple concussions in close proximity and repetitive injuries that accumulate over the course of time.

“When parents and coaches are involved we can create this environment and say, ‘I know you want to play and we want you to play but it’s not safe for you,’” Bishop said. “Especially when it comes from multiple angles then it validates it … I think hopefully, from what I hear, we’re getting much more of that community involvement.”

Bishop is holding a free presentation Sept. 13 at 7 p.m. at the Summit Medical Fitness Center. Bishop will discuss concussions and ways to defend against brain injury.

Orthopedic Rehab, a physical therapy office in Kalispell, spearheaded the implementation of a new program last year that helps doctors and trainers determine an athlete’s ability to return to play after sustaining a concussion. The Flathead Valley Sports Medicine Foundation purchased ImPact, which stands for Immediate Post-Concussion Assessment and Cognitive Testing. ImPact analyzes an athlete’s cognitive function, like reaction speed and memory. Naomi Taylor, an employee of Orthopedic Rehab and the head athletic trainer at Glacier High School, took the lead incorporating the computerized tests at Glacier and Flathead. ImPact highlights abnormalities and provides a set of data that can help doctors determine whether an athlete is ready to return to play.

“There have been several instances where I have been very thankful to have ImPact,” Taylor said. “ImPact has been a very useful asset. It does not make decisions for us, but it is another tool in our bag to help make the most informed decision we can for our kids’ well being.”

Taylor documented 21 concussions at Glacier last year. The majority occurred in football — six — while athletes in a wide range of other activities, like soccer, wrestling and basketball, also sustained concussions.

“Kids have a hard time seeing past Friday nights,” she said. “But I have to think long term. Sometimes that requires me being the bad guy.”

|

|

Flathead High School head football coach Russell McCarvel, right, works with his team while running drills at a recent Braves practice in Kalispell. – Lido Vizzutti | Flathead Beacon |

The Montana High School Association has taken steps in recent years to enhance concussion awareness and try to prevent multiple injuries.

MHSA rewrote its suggested guidelines for managing concussions based around the mantra “When in Doubt, Sit Them Out!” The guidelines ask officials to make coaches aware of an injured player and call an injury timeout. Once the official notifies the coach, it becomes the coach’s responsibility.

“Ultimately, the decision to return an athlete to competition rests with the coach, after the affected player is evaluated by an appropriate healthcare professional,” the guidelines state.

Officials do not need written permission for an athlete to return to play nor do officials need to verify the credentials of the appropriate health care professional, according to MHSA rules.

A majority of states have implemented tougher measures through legislation. Excluding Montana, 38 states have adopted youth concussion laws that center on the main principles of the Lystedt Law, the nation’s toughest return-to-play legislation. The Lystedt Law is named after Zackery Lystedt who suffered severe brain damage in 2006 after sustaining a concussion and returning to a middle school football game in Washington. The law requires any youth athlete suspected of having a concussion be removed from a game or practice. The athlete must be cleared by a licensed health care professional before returning to play.

|

Sun shines through American and Blackfeet flags flying over the yard of Bill Old Chief outside of Browning. Lido Vizzutti – Flathead Beacon | Click Here to enlarge |

On Aug. 24, Sen. Anders Blewett of Great Falls, in cooperation with the Brain Injury Alliance of Montana, announced a proposed law that would follow the standards of the Lystedt Law. The bill, called the Protection of Youth Athletes Act, is in honor of Dylan Steigers, a 21-year-old Missoula native who died in 2010 after sustaining consecutive concussions while playing football at Eastern Oregon University.

JC Weida, an associate athletic trainer at the University of Montana, is on the statewide committee that helped draft the Montana bill, which will be proposed at the upcoming legislative session this winter. The law would enhance awareness, education and prevention in Montana, and provide coaches, parents and athletes a clear rule to play by, Weida said.

There is already fear that politics could come into play and changes could be made that would weaken the law.

“We don’t want a bill passed that doesn’t do anything. Then all you’re doing is misrepresenting what you want done,” Weida said. “So there is concern there. The truth is, we’re talking about a kid’s brain.”

Another opposing force, perhaps the largest, is the age-old mindset in sports.

“The biggest problem we have to get through is a lot of coaches and parents are former athletes. When they were playing, they were told they could do that and just play through it,” Weida said. “That’s why I think the education component is so important. It’s educating and generating awareness.”