Last week a large group of visitors toured the Conrad Mansion near downtown Kalispell just like any other weekday between May and October. The tour lasted an hour, but it could have gone on much longer as enthusiastic guests seemed enthralled with experiencing a time that now survives mostly in black-and-white photos and inside this 13,000-square-foot relic.

“You’re really walking into a time machine. It’s as if you were living in 1890,” said Mike Kofford, a former executive director of Conrad Mansion Museum.

“It’s the best representation of the earliest years of the city of Kalispell. It’s absolutely a community landmark.”

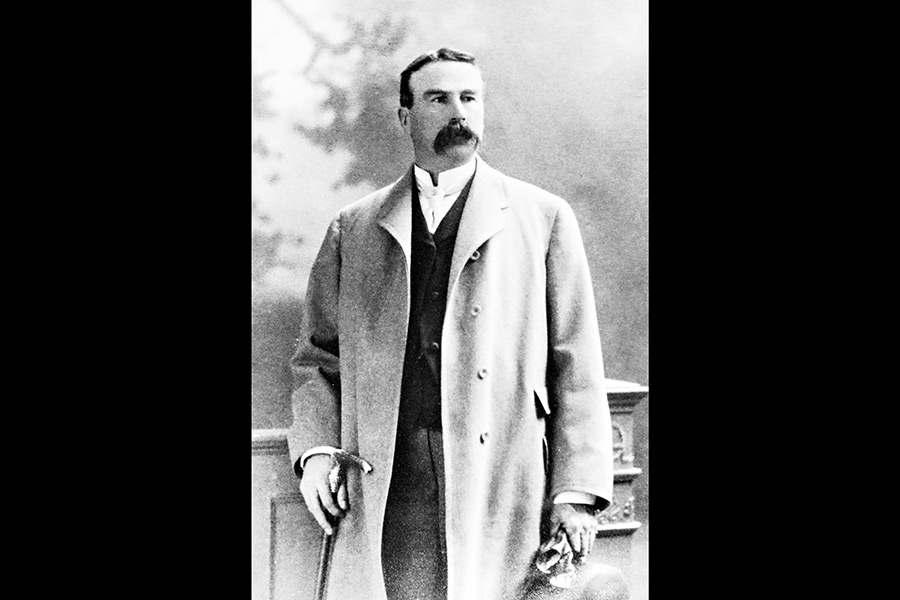

Completed in 1895, the Conrad Mansion is celebrating a pair of milestones this year. It was 120 years ago when Kalispell’s founding father, Charles E. Conrad, welcomed his family into the newly built manor that was designed by renowned architect Kirtland Cutter, who also designed Lake McDonald Lodge in Glacier National Park.

And it was 40 years ago when restoration efforts saved the mansion from ruin and transformed it into a revered public museum and memorial. The museum attracts nearly 9,000 visitors annually from May 15 through Oct. 15, when daily tours are offered, as well as in the offseason when private tours can be booked.

The large guestbook sitting in the entranceway of the Great Hall reflects the mansion’s far-reaching influence — signatures of visitors from everywhere exclaiming their appreciation for the site, which is listed in the National Register of Historic Places and has been called “the most authentic pre-1900 mansion in the Pacific Northwest.”

“There’s still secrets to discover and things that the house is telling us all these years later,” Gennifer Sauter, executive director of the mansion, said.

The forested landscape north of Flathead Lake beckoned to Charles Conrad when he was an ambitious entrepreneur and avid outdoorsman seeking a new horizon.

Born in Virginia in 1850, Conrad grew up on a plantation in the South, the second oldest of 13 children. When he was only 14, he was enlisted along with his older brother William in the Civil War as a member of Mosby’s Rangers, a skilled battalion of cavalry in the Confederate Army that sneaked behind enemy lines and disrupted the Union Army’s efforts. The boys fought in the last two years of the war before returning home to find their family’s plantation was struggling, like much of the South. Charles and William ventured West, arriving in Fort Benton in 1868 with only a silver dollar between them, as legends goes.

The boys developed into successful businessmen, taking over a mercantile company that transported supplies using riverboats along the Missouri River and wagons. Charles became known for building strong relationships with Indian tribes living throughout the Montana territory, and in the 1870s he helped negotiate a treaty between the British government in Canada and five tribes following the Nez Perce War.

Charles spent over 20 years prospering in Fort Benton as a multi-millionaire before the mysterious northwest corner of modern Montana called his name. On his way to Spokane in search of greater opportunity, Conrad journeyed the entire length of Flathead Lake in the fall of 1890 with his wife Alicia and their young child. The utopian beauty of the new land awed the Conrads, and Alicia would later say it seemed as though they had entered paradise.

Author James E. Murphy described this turning point in history in his 1983 book, “Half Interest in a Silver Dollar: The Saga of Charles E. Conrad.”

“The colors of fall marched up the foothills and mountains, blazing in the bright fall sun,” Murphy wrote. “As the Conrads watched the passing scenery, there began a love affair with the Flathead Valley that would warm their hearts and glow within them for as long as they lived.”

At the time, Demersville was the largest community in the valley. Conrad and his close friend, James J. Hill, the chief executive in charge of the Great Northern Railway, devised a plan to build the railroad’s new division point for the region in a new community north of Demersville.

With opportunity in mind, Conrad founded the Kalispell Townsite Company with a few men from the railroad, and they began platting a new community. A friend of Conrad’s recommended it be named after the tribe of Indians known to frequent the area.

In 1891, Kalispell was born. Within only a few years, the community had blossomed with Conrad as its most famous and successful resident. He was involved in banking, real estate, mining and cattle ranching.

“Everything he touched turned to gold,” said Mary Miers, a staff member for eight years at Conrad Mansion.

He was a passionate outdoorsman who took his family on adventures into modern day Glacier National Park, and established a large bison herd along his 72 acres of property in Kalispell. The herd, which had a strong bloodline, later helped establish the National Bison Range in Moiese.

Conrad’s time in Kalispell was short. He died Nov. 28, 1902 in his bedroom in Kalispell. Historians say it was from complications associated with diabetes and tuberculosis. The news of his death made headlines across the country — “Montana Pioneer Dies,” the Salt Lake Tribune read in November of that year. The newspapers described him as one of Montana’s most prominent and important citizens, similar to the Copper Kings of Butte and Anaconda.

Indeed, Conrad left behind a massive legacy. But not long after his passing, as Kalispell thrived into the 20th century, the mansion that stood as prominent as the man who built it began crumbling with time.

In early October of 1973, Chris Vick, the great-grandson of Charles Conrad, met with the Kalispell City Council in a closed meeting. On behalf of the family, Vick offered the city a monumental gift — the historic Conrad Mansion.

Completed in 1895, the 13,000-square-foot mansion along Woodland Avenue boasted an enormous stature. It sat in the middle of an entire city block with three stories and 26 rooms and included state-of-the-art features for the turn of the century, including electricity and an elevator.

Yet the famous mansion had become hardly distinguishable by the 1970s. Many of its windows were boarded up. Overgrown shrubs and trees engulfed the run-down facade. Vandals had even broken in and looted parts of the building.

A small mobile home sat on the southeast corner of the property where Alicia Conrad Campbell, the youngest daughter of Charles and Alicia Conrad, was living as an elderly woman, unable to pay the heating bills for the massive old home. Several years after Alicia and her late husband George Campbell moved into the trailer outside, it was difficult to even travel through the mansion as mountains of clutter climbed toward the ceilings, reflecting Alicia’s habit as a hoarder.

Seeing the once-elegant home fall into further disrepair, Alicia and her grandson, Vick, offered it to the city to be restored and preserved as a museum and memorial open to the public.

The proposal sparked a citywide debate. Several councilors and residents expressed support for preserving the mansion using city funds while others claimed it would be a misuse of tax dollars to save the dilapidated site. The city council eventually balked and put the decision up to voters. In March of 1974, Kalispell voters overwhelmingly rejected the city’s acceptance of Conrad Mansion, with 1,325 against and 860 in favor.

In the aftermath of the vote, the Conrad Mansion’s fate sat in limbo. Mayor Larry Bjorneby and other supporters of the city’s acquisition, including councilor Everit Sliter, were distraught after Kalispell residents opposed funding a local landmark.

“We thought the house was a treasure that should be preserved,” Sliter recalled recently.

A local nonprofit group, led by chairman Sam Bibler, took on the large task of saving it with the help of Alicia and Vick.

It was around this time when volunteers began cleaning up the clutter. The shrubbery was trimmed away from the outside, revealing an eminent presence, panels of Tiffany-style stained glass and diamond paned windows. From inside the uniquely designed rooms, treasures emerged, such as historic guns; a painting of Teddy Roosevelt, who stayed at the mansion on a few occasions; original Charles M. Russell sculptures given to the Conrads by the famous Montana artist; handmade oak tables and desks.

A small pathway was cleared through the mansion and residents began touring the mysterious relic for the first time.

“I remember that as the turning point. That was when people walked through the house and they saw that this was truly something special,” Nikki Sliter, the wife of Everit Sliter, recalled recently. “That’s when public opinion changed.”

In December 1974, the city accepted the Conrad Mansion as a gift from Alicia Conrad and her family. As part of the agreement, the nonprofit group would be responsible for operating and funding the site as a museum.

Public support swelled as restoration efforts took place throughout 1975. Thanks to Alicia’s collecting habits and people giving back items that were taken over the years, roughly 90 percent of the home’s original items were placed back throughout the home. By July 1976, the mansion was formally unveiled and regular tours began.

“It’s an icon — the house that the founder of the city built,” Everit Sliter said. “It’s truly awesome inside.”

Today the mansion is almost completely supported by public visitors, fundraisers and memberships.

There are about a dozen guides every year who give daily tours; each guide must memorize 23 pages of history before earning the honor of wearing white gloves and leading a tour. In recent years, much-needed repairs have been paid for by community businesses and residents, further illustrating the widespread support for the mansion.

“It really is a source of community pride. It’s a wonderful place with a lot of historical connections,” Miers said. “When you think about little Kalispell, Montana and what Conrad did for the community, it’s pretty incredible.”

For more information about Conrad Mansion, visit http://www.conradmansion.com.