On Aug. 25, 1916, President Woodrow Wilson picked up a dip pen in the White House and scratched his signature on H.R. 15522, the Organic Act, creating the National Park Service.

That simple act of putting pen to paper was the culmination of years of work by naturalists, conservationists and even industrialists to convince the federal government to create a single bureau to care for the 7,290 square miles of park land set aside for the enjoyment by the masses.

But in the wilds of Northwest Montana, the creation of a parks bureau passed with little fanfare in Glacier National Park, which was in the midst of another busy summer tourist season (about 12,800 people visited the park that year, which today is about the same number that passes through the west entrance on an average day in July). Of course, back then, it wasn’t possible to spend a day driving through the park on Going-to-the-Sun Road, which wouldn’t be completed for another 17 years and stands out today as one of the region’s most popular attractions.

“The idea of doing the park in a day – of just getting in your car and driving up the Sun Road – was an impossibility (in 1916),” said author and historian Ray Djuff. “This was a park that had to be seen and experienced from its trails.”

In 1916, one of the most popular ways to travel to Glacier Park was by train. Great Northern Railway President Louis Hill was an ardent and early supporter of the park because he knew that such an attraction along his rail line would boost ticket sales aboard his trains. Within weeks of the park’s creation in 1910, Hill’s ad men were filling city newspapers across the country with advertisements promoting the Great Northern as the only way to visit the “American Alps.”

Every summer, the railroad would offer special fares to and from Glacier Park. It cost $48 in 1916 to ride in a first-class cabin aboard the railroad’s premier train, the “Oriental Limited.” The daily passenger train featured electric lighting and departed Chicago at 10:15 p.m., arriving in East Glacier Park two days later. Those on a budget could secure a spot aboard a lower-class sleeping car for as cheap as $4.75 from Chicago and $3.75 from St. Paul. Regardless of class, however, the train was a luxurious, albeit time-consuming, means of traveling across the landscape, according to author Mary Roberts Rinehart, who published “Through Glacier Park” in 1916.

“Getting to (Glacier), remote as it seemed, had been surprisingly easy – almost disappointingly easy. Was this, then, going to the borderland of civilization, to the last stronghold of the old West? Over flat country, with inquiring prairie dogs sitting up to inspect us, the train of heavy Pullman diners and club cars moved steadily toward the purple drop-curtain of the mountains,” she wrote.

“An occasional cowboy silhouetted against the sky; thin range cattle; impassive Indians watching the train go by; a sawmill, and not a tree in sight over the vast horizon. Red raspberries as large as strawberries served in the diner, and trout from the mountains that seemed no nearer by mid-day than at dawn.”

The wooden depot at East Glacier Park (which still greets Amtrak passengers twice a day) was the final stop for passengers heading west to visit the new national park. Blackfeet Indians were hired by the railroad to greet passengers and perform traditional dances at the station and the nearby Glacier Park Lodge that was built and opened by the railroad in 1913. On occasion, the railroad would even pay the Blackfeet extra to induct special guests into the tribe, which in later years included President Franklin Roosevelt, actor Clark Gable and a prince from Norway. After taking in the show at the station, passengers would walk across the street to the massive lodge.

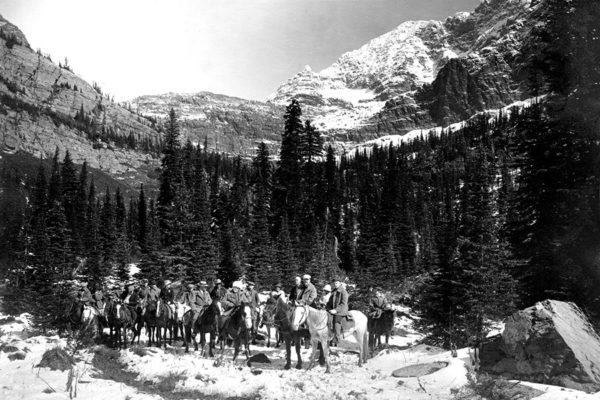

The Great Northern Railway built a chain of hotels and chalets in and around Glacier Park in the early 1910s and the Glacier Park Lodge was among its most spectacular. The 155-room lodge was built to look like a post-and-beam log cabin with Swiss influences. The hotel even featured a pool in the basement. It was from here that many visitors would begin their trip through Glacier Park. While people were free to tour the park at their leisure, the railroad worked hard to promote trips that ferried people to their other accommodations in Glacier. Automobile and stage tours from the Glacier Park Lodge went to St. Mary, Many Glacier and Two Medicine and could be purchased for anywhere from $1.50 to $12. Visitors wishing to journey deeper into the park could hire guides and horses from the Park Saddle Horse Co.

In 1916, single-day passage into Glacier Park cost 50 cents and a season pass cost $2. In 2016 currencies, the season pass would cost $45.93, only 93 cents more than what it is today.

A complete tour of the park – with stops at all of the chalets and scenic highlights such as Iceberg Lake and the Blackfeet Glacier – could be completed in 10 to 14 days. For those who didn’t have the luxury of a long vacation, the Department of Interior published a list of special tours lasting from one to seven days. The seven-day tour, which took visitors to Many Glacier, Granite Park and elsewhere, cost $33.70 per person, not including meals and lodging.

A guide to Glacier Park published in early 1916 advised visitors on how to dress and pack for a trip into the wilds of Montana.

“As a rule tourists are inclined to carry too much,” the guide stated. “A very inexpensive and simple outfit is required – old clothes and stout shoes are the rule.”

Among the suggested wardrobe items was one sweater or old jacket; two pairs of wool underwear (medium weight); three pairs of socks; one pair of hunting boots; two pairs of cotton gloves; one old felt hat and one “saddle slicker,” or raincoat. Of course, if anyone forgot to pack an item, the “well-stocked commissaries” would gladly sell them another.

The first part of a visitor’s seven-day journey across Glacier, however, didn’t require “stout shoes,” just an ability to sit back and enjoy the drive to Many Glacier, which departed East Glacier promptly at 8:15 a.m. In 1916, motorized tours of Glacier Park were still a new concept, having only begun in 1914. Glacier was the first park in the U.S. that offered driving tours. According to Superintendent S.F. Ralston’s annual report, there were 83 miles of roads within the park and another 50 miles outside the preserve that was under the supervision of the park.

Speeds on park roads were especially slow, according to Djuff, who said 15 miles per hour was usually the limit, although in some straight sections more adventurous drivers could speed up to 20 miles per hour. Because automobile lights were not especially bright back then, driving was only permissible between the hours of 7 a.m. and 9:30 p.m. And pack trains and horses always had the right-of-way on any park road.

Arriving at Many Glacier, visitors would find the park’s newest and grandest hotel on the shores of Swiftcurrent Lake, than called McDermott Lake. The Many Glacier Hotel opened in the summer of 1915 and Hill dubbed it “the showplace of the Rockies.” A visitor could spend $4 to spend the night in one of its more than 200 rooms, or $5 if they wanted one with a bath. At the time, it was the largest and perhaps most luxurious hotel in all of Montana and even featured a telephone in every room.

Many Glacier served as base camp for the seven-day tour. On the second day, participants would horseback ride to Iceberg Lake, one of the most iconic trails in the park. While today there are more than 700 miles of trail, the system was still in its infancy in 1916. The superintendent’s report from that year outlines much of the work that was done, including the construction, extension and improvement of trails to Snyder Lake, Granite Park and Grinnell Glacier. A new Sperry Glacier Trail was also constructed to an average width of 4 feet. While Superintendent Ralston boasted of the work his trail crews accomplished, it wasn’t enough for some people, especially Hill. The railroad-president-turned-park-promoter frequently chastised park officials for spending too much time building employee housing and not enough time building trails. “The people who return each year are becoming tired of the old trails and want something new,” he wrote in 1920.

While many visitors took guided tours with horses, almost as many toured the park on their own two feet, although back then hiking was called “tramping.” Djuff said those looking for a more inexpensive vacation could frequently stay at the many campsites the railroad built around the park.

On the third day of the weeklong tour, participants rose early for breakfast before hitting the trail for Granite Park, site of one of the half-dozen chalets the railroad built in the early 1910s. Inspired by those found in the Swiss Alps, the chalets were wilderness hotels located at spots personally selected by Hill. Although remote, visitors were not roughing it at the chalets as a service staff decked out in Alpine-inspired uniforms waited on them for meals (female waitresses were required to wear a heavy Swiss dress).

For some of Glacier’s visitors, Granite Park was the furthest west they ventured. When Glacier was officially designated a park in 1910 and the railroad began building up its infrastructure, it was forced to focus its investments on the east side of the park because much of the west side had already been developed. Tourists had already been venturing to the Lake McDonald area for years and George Snyder constructed the first hotel there in 1895 (it was later replaced by the Lake McDonald Lodge in 1914).

After spending the night at Granite Park and consuming another hearty breakfast, visitors would return to Many Glacier. On the fifth day of their tour, they would take a 6-mile horseback ride to Cracker Lake. Although this pristine lake surrounded by an amphitheater of mountains looks untouched by man it was actually the site of a mine, pieces of which would have still been evident in 1916. The Cracker Lake Mine was established after copper ore was discovered below Mt. Siyeh in 1898 and a town site was established at nearby Cracker Flats. During its peak in the early 1900s, more than 600 people lived and worked there and the town of Altyn had a store, a post office, hotel, several saloons and even a newspaper. Even today, hikers can find leftover machinery from the mine at Cracker Lake.

Mining operations like the one found at Cracker Lake was one of the reasons naturalist and writer George Bird Grinnell was so adamant about creating a national park in Northwest Montana. For years, prospectors and people looking to make a quick buck had rushed to the area that would become Glacier Park to look for minerals and timber. That came to an end when the park was created in 1910.

The final part of the seven-day journey across Glacier Park took visitors from Many Glacier over Piegan Pass to the Going-to-the-Sun Chalets. Today Sun Point isn’t much more than a wide spot along the Sun Road, but back in 1916 it was one of the busiest places in the park.

“The Going-to-the-Sun Chalets were the crossroads of Glacier Park and most saddle trips ended up there,” Djuff said. “You could come in from Lake McDonald, Granite Park, Many Glacier or Two Medicine. It was one of the busiest sites in the park and there were people constantly coming and going.”

The Going-to-the-Sun Chalets, or Sun Camp, as it was called by some locals, had a large dining room, laundry building and two guest dorms that could host upwards of 200 people a night. Because the Sun Road had not yet been constructed, the only way to get to and from the chalets from the entrance at St. Mary was by boat.

Despite its popularity, Sun Camp only existed for 30 years before it was deemed obsolete with the construction of Going-to-the-Sun Road, which took 11 years to build and was completed in 1933. With people now able to cross the park by auto in just a day, the need for chalets spaced a day’s hike or horseback ride apart was unnecessary. The park changed drastically as more and more people arrived by car and many of the chalets were torn down following the Great Depression and World War II. What was left after that downsizing makes up much of the park’s core infrastructure today.

Despite the many ways the park has changed in the last century, the reason visitors flock here remains unchanged — an opportunity to visit America’s greatest spaces.

It was a fact not lost on one of the many visitors to Glacier Park in 1916.

“I have traveled a great deal,” Rinehart wrote a century ago in Through Glacier Park. “The Alps have never held this lure for me. Perhaps it is because these great mountains are my own, in my own country. Cities call – I have heard them. But there is no voice in all the world so insistent to me as the wordless call of the Rockies. I shall go back. Those who go once always hope to go back. The lure of the great free spaces is in their blood.”