The Toughest Town in Montana

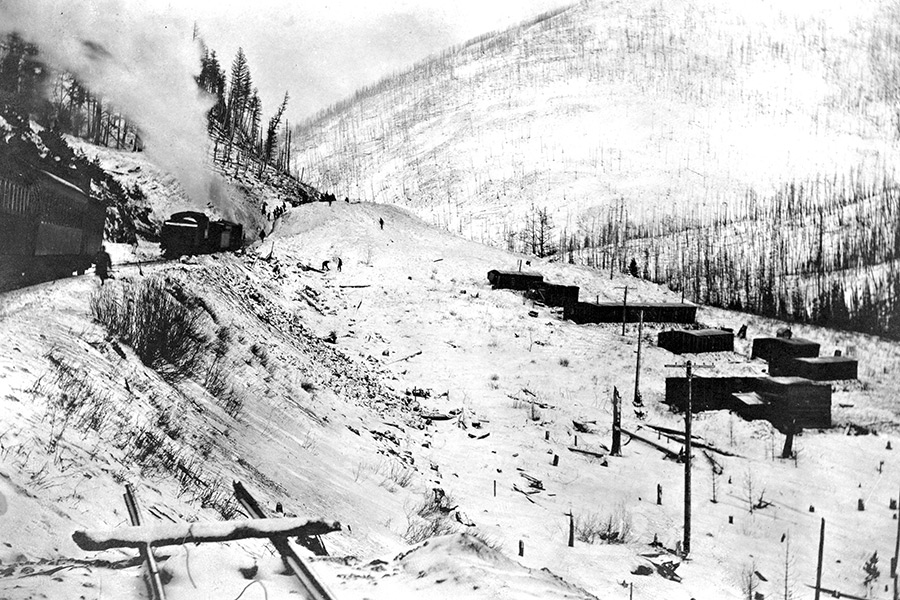

In 1890, a rough-and-tumble railroad town called McCarthyville was born on the southern edge of Glacier National Park. Two years later, it was gone.

By Justin Franz

On a frigid February day on the southern edge of Glacier National Park, an unrelenting wind whips down Bear Creek and across the flats five miles west of Marias Pass. Few cars travel the snow-covered U.S. Highway 2, which only days earlier was closed due to avalanches.

Nearly 130 years after John F. Stevens documented Marias Pass for the first time, this remote piece of Montana remains almost as wild and rugged as it was before humans arrived. Get a flat tire out here and you can forget about calling AAA for help — there’s no cell service for miles around. Run off the road on a snowy night and you’re facing a long, cold wait, if you’re lucky. Today, the lonely stretch of highway just west of Marias Pass sports a bar, an inn, a few campgrounds and not much else. This time of year, winter’s silence is usually only interrupted by a passing train.

But it wasn’t always this quiet. In the years immediately after Stevens mapped the route over Marias Pass for the Great Northern Railway, this strip of territory, which runs along the Middle Fork of the Flathead River in the shadow of the Lewis Range, was anything but peaceful. In 1890, the town of McCarthyville — or McCarthysville, according to some historical records — sprung up out of the wilderness. Fueled by the westward expansion of the railroad, McCarthyville’s population exploded to more than 1,000 within a few months, with dozens of bars, gambling halls and brothels for the rowdy railroad workers to find trouble. Soon, McCarthyville earned the moniker as “the toughest town in Montana,” and the king of this wild frontier settlement was a 20-year-old kid from Kalispell named Eugene McCarthy.

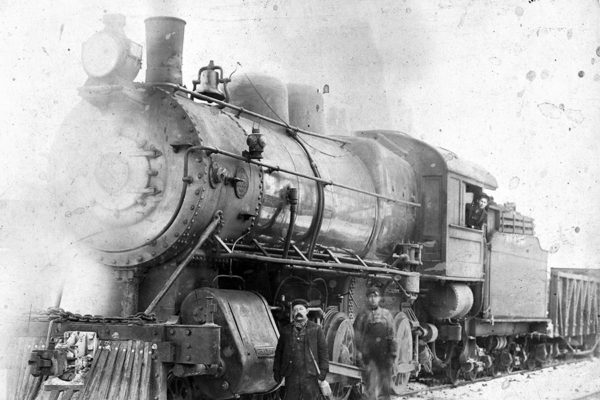

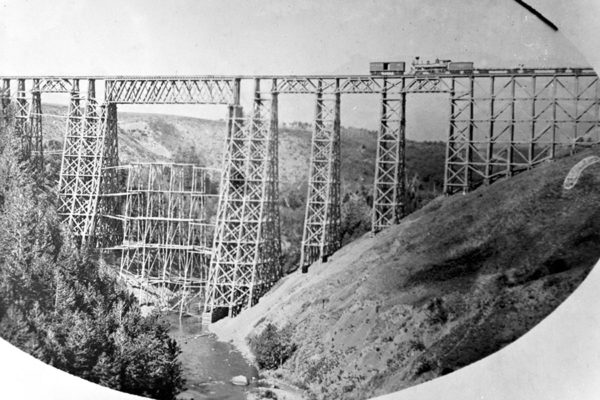

In the late 1880s, James J. Hill, a brash and bombastic railroad builder, had set his sights on the West. Hill, a Canadian-born executive who had settled in St. Paul, Minnesota, was determined to grow his Great Northern Railway from a small Midwestern railroad to a cross-continent player like the Union Pacific and Central Pacific, which had completed the Transcontinental Railroad a decade earlier. To do that, he needed to find the easiest route across the Rocky Mountains.

For years, rumors abounded of a mysterious low passage to the Pacific Northwest. Lewis and Clark tried and failed to find it in 1806. Engineer James Doty almost found it when surveying a potential route for the Transcontinental Railroad in 1854 but was pulled back by a government official sympathetic to the South who didn’t want the northern states to hold the strategic advantage of the first railroad to the Pacific. Despite others’ past failures, Hill was not deterred. In 1889, he hired Stevens, a noted engineer, to head West and find the Marias Pass.

According to a legend later promoted by the Great Northern, Stevens set out looking for the pass in November 1889. The following month, he arrived at Blackfeet Agency (Browning today) and hired a local guide to take him to Marias Pass. Not long into the journey, the guide grew ill. Stevens left him by a fire and continued on, knowing he was close to his goal. On a bone-chilling December day, Stevens found a wide spot between the mountains where the water flowed to the Pacific: the great pass was found. But by the time he had made the discovery, it was nightfall with below-zero temperatures. Stevens tried to build a fire to stay warm but instead ended up walking back and forth all night to stay alive. At dawn, he headed east where he discovered his Native American guide half frozen to death. He helped rehabilitate the man and continued east with news of the new Northwest passage. At 5,213 feet, Marias Pass remains one of the lowest crossings of the Continental Divide in the United States.

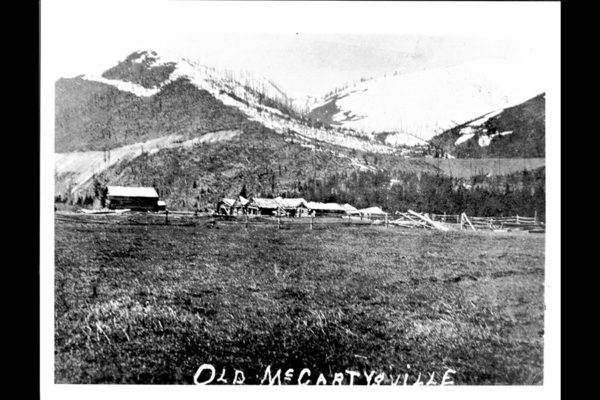

In 1890, tracklayers sprinted west across the plains bound for Marias Pass and the Pacific Ocean. By October, the Great Northern had arrived in Havre and the railroad was knocking on Cut Bank’s door by New Year’s Eve. Meanwhile, an enterprising 20-year-old from Kalispell named Eugene McCarthy had headed east looking for fortune. While many men of the era placed their bets on finding silver and gold, McCarthy was determined to make his millions with timber and land. In late 1890, McCarthy found a wide meadow on the west side of the pass surrounded by trees that were ideal for the wooden ties used in constructing railroads. The young entrepreneur also realized that the meadow — with plenty of space for buildings and a creek meandering through the middle — was the perfect spot for a town.

McCarthy filed a Declaration of Occupancy and started plotting a townsite. The young man’s move to settle the land quickly caught the attention of the railroad construction company, which knew it was the most suitable spot for a work camp. The company threatened to sue McCarthy but realized that could lead to a lengthy court case, so they decided to settle and split the land down the middle. McCarthy was able to build his town on one side of the creek; the construction company put its camp on the other.

State law prohibited the sale of alcohol within 2 miles of a railroad construction camp, unless it was within the boundaries of an incorporated community. Not wanting to miss out on the chance to serve thirsty workers, McCarthy quickly incorporated the town and appointed himself mayor, the youngest in the state. By December 1890, McCarthyville had 100 residents, six saloons, three restaurants and one store, according to a story in the local Kalispell paper. Some of McCarthyville’s residents were petitioning for a post office, perhaps believing their little hamlet would soon be a bustling town like Havre and Cut Bank. The story, published in the Dec. 10 edition of the Weekly Inter Lake, hypothesized that the young McCarthy was well on his way to becoming a business tycoon. “By next winter we expect to see him spoken of as a bloated bond holder,” the paper wrote.

But McCarthy’s plan wasn’t unique. During the construction of the Transcontinental Railroad, small communities dubbed “Hell On Wheels” cropped up along the Union Pacific in Nebraska, Wyoming, Colorado and Utah. The little boomtowns had saloons, brothels and other services for the workers. Most of them would fizzle out after a few months. With a population of mostly male workers who had little to do but drink and gamble in their free time, “Hell On Wheels” communities gained a reputation for violence. McCarthyville was no exception.

In January 1891, McCarthyville had its first “baptism of blood,” according to one of the local papers, when two masked men murdered three others in cold blood. Newspapers at the time reported that Henry Hart and Jim Cummings opened fire in a tent where five men were playing cards. The commotion knocked over a candle that had been the sole light source in the tent. “Shot after shot was fired into the group in the darkness, and the groans of the victims soon told that the shots had the desired effect,” The Fort Benton River Press reported a few days later. One of the victims, Jerry Boudoin, was “literally riddled with bullets,” having been shot eight times, including once straight through the brain. After shooting the men, Hart and Cummings combed their bodies for money and fled the scene.

Two of the card players survived, and one of them, named Warner, had rolled out the back of the tent and made his way to McCarthyville. In town, McCarthy rounded up a posse and headed to the scene. Near the tent, they found two men dead and one seriously wounded. Blood stained the floorboards and the surrounding snow. Down by the creek, they found the body of a third man — his blood dyeing the water — and surmised that after the robbers shot the man, they dragged him around before abandoning him in the water, according to John Fraley’s book, Wild River Pioneers.

After surveying the scene, McCarthy and his crew headed east in hot pursuit of the killers. But after three days and two nights on the trail, they returned empty-handed. Meanwhile, deputies 70 miles away in Demersville heard of the murder and headed to Marias Pass. On the way, they found and arrested Hart, who was holed up in a cabin. They took Hart to McCarthyville, then joined McCarthy’s posse and headed back east after hearing that Cummings had been spotted on his way to Cut Bank. Cummings was arrested soon after.

But bloody robberies were not the only way to expire in McCarthyville. Over the course of the town’s short existence, more than 200 people died, many in a makeshift hospital that was set up by the railroad. To run the clinic, the railroad hired a veterinarian who was paid $1 for every man treated. The doctor was aided by a man known as Big Swede who started every day by dragging the bodies of those who died the day before to the edge of town and burying them in shallow graves. If the ground was frozen, the Swede simply covered the bodies with snow, only to have them re-emerge come spring.

Conditions at the hospital were dire. An April 1891 story published in the Inter Lake titled “Hospital Horrors” detailed the conditions: “On account of the miserable accommodations la grippe and pneumonia are very prevalent, and the poor men sick, suffering and unable to get away lay in the rude place used as a hospital until death in many cases brings them a release. One victim who died at 4 o’clock p.m. asked the nurse in charge for a drink of water at 11 o’clock a.m. of the same day, and the heartless wretch compelled him to take a bucket and go 100 yards through the snow and get it for himself. Another poor soul lay in his dying agony when a piece of dirt fell from the mud roof into his eye. A bystander asked the attendant why he did nothing to remove it, his reply was: Oh! He will die pretty soon anyhow.”

The hospital only improved after McCarthy and some local residents took matters into their own hands. One day, a small mob gathered outside the hospital tent and demanded to see the proprietors. When the Big Swede opened the door, he was whacked with the butt of a rifle. That was all the doctor needed to see before ducking out the back door, never to be seen in McCarthyville again.

While the community’s short life was mostly marked by death, there was one baby born there. According to an 1891 report, “the first baby born in McCarthyville is the ‘personal property’ of Mr. and Mrs. G. Card. It is a strong and handsome little fellow and has been christened Gust Ottawa Card after the genial proprietor of the ‘Elk House’ on Central Ave.”

McCarthyville reached its peak in mid-1891. At the time, the town had more than 1,000 people and 32 bars. On Sept. 14, 1891, the Great Northern’s rails reached the summit of Marias Pass. A week later, the track entered McCarthyville. The arrival of the railroad was a cause for celebration, but it also signaled the beginning of the end for the little town. By the end of the year, the rails had reached the Flathead Valley and workers began to abandon the wilderness settlement. Initially, residents around Kalispell began to worry that the workers from McCarthyville would bring their rowdy ways to town, but the Jan. 19, 1892 issue of the Helena Independent reported that most of the track builders continued on to “Kootenai Country, where there is less evidence of civilization.” By 1893, only a handful of people were left in McCarthyville. Even the town’s self-appointed mayor and namesake had moved on. McCarthy went on to be a justice of the peace in Kalispell for 22 years.

But McCarthyville did not go out with a whimper. In fact, Fraley said, “McCarthyville was born in violence and went out in a blaze of glory.” In August 1893, four men robbed a Northern Pacific Railway train near Big Timber in south-central Montana. After stealing $2,000 worth of cash and goods, they headed north. A few weeks later, they reached Midville on the east side of Marias Pass. There they convinced a fifth man to help rob a Great Northern train.

Meanwhile, a growing posse was chasing them across the state and had tracked them to the Rocky Mountain Front. In early October, the posse tracked the robbers to a cabin in Midville, where they came out shooting and quickly escaped into the mountains. Federal Marshal Sam Jackson telegraphed for help from Flathead County. A few days later, Sheriff Joseph Ganger, Flathead County’s first top lawman, arrived with his own posse. By then, the robbers had made it to what was left of McCarthyville, where another shootout ensued. The men escaped yet again, although Ganger and his crew eventually caught up to them. Over the ensuing weeks, Ganger’s men would capture three of the criminals, seriously wounding one, and kill the other two. The west slope of Marias Pass grew quiet once again.

Although the lore of “the toughest town in Montana” is bathed in blood and violence, for some who lived there, it was a time of bliss in a wilderness that remains untamed to this day. Years after the town’s demise, a man named Charles Sturman was regaling a newspaper reporter with tales of his life in McCarthyville. Unlike so many stories of the town, Sturman’s McCarthyville was a peaceful place, punctuated by the stunning nature surrounding it. “That summer,” the reporter wrote, “was one of the most enjoyable of their lives. The country was wild and untouched, virgin timber clothed the mountains, wild game abounded and save for the members of the crew or an occasional small party of Indians the country was uninhabited.”

Eventually, U.S. Highway 2 was constructed over the pass, but the wilderness today is nearly as unspoiled as it was during McCarthyville’s heyday, except that when the snow melts now, there won’t be any bodies, only new life.

Special thanks to the Northwest Montana Posse of Westerners, John Fraley, the Northwest Montana Historical Society and the Stumptown Historical Society.

Read more of our best long-form journalism in Flathead Living. Pick up the spring edition for free on newsstands across the valley beginning March 15. Or check it out online at flatheadliving.com.