Dating back to 2005, a team of local researchers has been venturing into the alpine heart of Glacier National Park twice a year, armed with an array of scientific instruments, to conduct foundational work that could help explain the impacts of climate change in the high country.

Earth scientist Adam Clark characterizes the team’s effort as “meat and potatoes glaciology,” describing the years-long study of glaciers and their internal dynamics as a rustic project that trades the comforts of an indoor lab for the rugged environs of Glacier Park.

“We’re literally going out there with heavy metal probes and using snow pits and measuring the depth of snow at certain points,” said Clark, a Whitefish resident and scientist with the U.S. Geological Survey.

“The work is super labor intensive. You have to go live on the glacier for several days in these remote places to get this work done.”

The rigorous endeavor is providing clearer insight into the behavior of glaciers and how they react to local and regional climate. It’s also producing robust quantitative data detailing Sperry Glacier’s retreat.

The local research is corresponding with a larger study spanning 50 years of data that outlines Montana’s retreating glaciers, which have been reduced in size by as much as 85 percent in some cases.

According to new research published by the U.S. Geological Survey and Portland State University, the state’s glaciers have, on average, shrunk by 39 percent and only 26 glaciers are now larger than 25 acres, which is used as a guideline for deciding if bodies of ice are large enough to be considered glaciers.

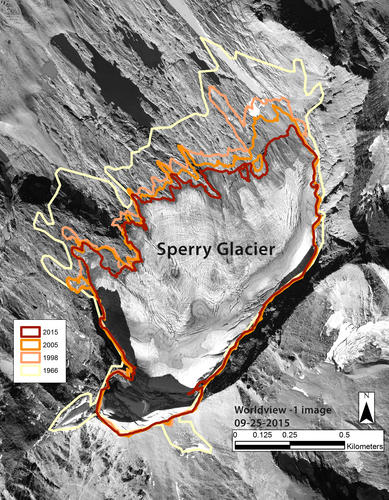

The agency’s data include scientific information for the 37 named glaciers in Glacier National Park and two glaciers on U.S. Forest Service land. Scientists used digital maps from aerial photography and satellites to measure the perimeters of the glaciers in late summer when seasonal snow melted and revealed the extent of the glacial ice. The areas measured were from 1966, 1998, 2005 and 2015/2016, marking approximately 50 years of change in glacier area.

Scientists say this research is shining a light on the looming impacts of the changing climate, ecologically and otherwise.

“The park-wide loss of ice can have ecological effects on aquatic species by changing stream water volume, water temperature and run-off timing in the higher elevations of the park,” said lead USGS scientist Daniel Fagre.

Portland State geologist Andrew G. Fountain partnered with USGS on the project and said glaciers in mountain ranges throughout the United States and the world have been shrinking for decades, as evidenced by this latest data.

The research is part of a larger, ongoing USGS glacier study in Montana, Alaska and Washington that is documenting mass balance measurements that estimate whether the total amount of ice is increasing or decreasing at a particular glacier.

In Glacier Park, Fagre, Clark and others have been studying the intricate changes sweeping the high country, specifically Sperry Glacier.

The results of the team’s field research have reaffirmed that the glacier hugging the north slopes of Gunsight Mountain, once one of the largest in the national park, is continuing to recede and lost 9 percent of its surface area between 2005 and 2015, or roughly 861,112 square feet. The glacier, which spanned 216 acres in 2005, lost about 4.37 meters of water equivalent averaged across the entire formation in that span of time, Clark said.

Sperry’s terminus, which is the end of a glacier at any given point in time, has continually retreated overall with each measurement interval, although selected small areas have slightly advanced, according to the research. The largest changes occurred around the glacier’s northernmost edges, which is its lowest elevation. At this location, many small fingers of ice have melted away or separated from the main ice body, exposing islands of bedrock, according to the research.

The information was published earlier this year in a paper authored by the research team: Clark, Fagre and Erich Peitzsch; Blase Reardon with the Colorado Avalanche Information Center; and Joel Harper with the University of Montana Department of Geosciences.

As its name suggests, Glacier Park is well suited for the study of glaciology. Massive valley glaciers up to 1,000 meters thick originally carved the landscape into sawtooth peaks and hanging valleys, forming its present identity. An estimated 150 glaciers existed in the present-day national park as early as 1850, but more than two-thirds had disappeared by 1980, according to research by P.E. Carrara and R.G. McGimsey. The glaciers that did survive — 25 as of today — were reduced in size and have been actively retreating to varying degrees, evidenced in a seminal research paper published in 2003 and co-authored by Fagre and Myrna H. P. Hall. For example, Sperry Glacier lost nearly 35 percent of its surface area between 1966 and 2005, according to Fagre’s study.

In the summer of 2005, Fagre embarked on the current research project with Reardon, formerly with the USGS, that is the first of its kind in the region. Their attention centers on Sperry Glacier and its mass balance, meaning the amount of snow and ice that accumulates and is eventually lost on a glacier. In other words, “It’s like a bank account, and we’re trying to estimate the cash in and cash out,” said Clark, who joined the project in 2008.

Each May, when snowpack is at its peak, Clark and his fellow researchers ski into Sperry Glacier and collect measurements from the same eight long-term sites, studying snowpack depths and density. They return at the end of summer and compare the levels and see how much snow has melted and the amount of ice melt.

Sperry Glacier is unique in that it’s a cirque glacier, meaning it is formed in a bowl-shaped depression on the side of a mountain. Its characteristics and patterns are different than, say, a glacier flowing out of a valley.

“We’re trying to figure out how that glacier actually works,” Clark said.

The research at Sperry shows that most years it has a negative annual balance, meaning it is cumulatively losing water, which explains its retreat.

Clark hopes the long-term research at Sperry will help researchers better understand glaciers and their diminished presence on the landscape. Glaciers are unique in a variety of complex ways, and some are doing better than others, Clark said. The one unifying characteristic is that they are all undoubtedly changing.

“All the glaciers in the park are shrinking,” Clark said. “There’s just some uncertainty as to what the rate is right now. We don’t fully understand all the processes that control these different glaciers.”

“By looking at one particular glacier,” he added, “we’re beginning to understand how those topographic effects basically work on the glacier and change its mass balance.”