When Pete Costain first moved to Whitefish in the early ‘90s, sprawling networks of trails scored the landscape, providing a small but growing contingent of dedicated mountain bikers with a glut of single-track opportunities right outside their collective back door.

Semi-legal, user-built biking and hiking trails, often constructed by clandestine groups of local riders, looped like clover leaves through the forested acreage surrounding Haskill Basin, Whitefish Hills, Spencer Mountain, and Iron Horse, tracking across a patchwork of state, federal and private land with variable futures and features, and a whole lot of prime development potential.

The fog of adrenaline that characterized those early years, tinged with a take-it-for-granted sense of entitlement to the community’s wide-open spaces, obscured a frightening reality that reared its head in 2003, when state and federal land management agencies began moving forward with plans to sell off parcels that anchored the trails.

A public-lands dispute began brewing and animated the local riders, hikers, runners, skiers, dog-walkers, and wildlife advocates who had staked out interest in the trails, roiling them into action.

At the time, the mountain community was buffeted with development pressure as growth swept across the Flathead Valley and the Montana Department of Natural Resources and Conservation turned an eye toward real estate proposals to maximize profits for thousands of acres of School Trust Lands around Whitefish.

Overseen by the DNRC, School Trust Lands are the product of the 1864 Territorial Act, a law that preceded Montana’s statehood and reserved two square miles of land in each of the territory’s townships, any profits from which would support public schools.

Some of the School Trust Lands in question, like Spencer Mountain, had existing, user-built trail networks on it, and the prospect of losing recreation access to development worried not only bikers and hikers, but also members of the Whitefish conservation community.

Rather than respond with bluster, the different corners of the community came to the table with impassioned resolve, and as the idea of building an expanded trail network as a mechanism to conserve the landscape took shape, it eventually shifted the course of local land management.

Suddenly, the notion that conservation, recreation and forest management could not only coexist, but also strengthen one another and work hand in hand, began rising to the fore of the conversation. It’s a concept that has since crept into other community trail projects throughout the region, but 15 years ago it was relatively new ground to cover for land users and land managers alike.

The local group brought its concerns to the Montana Land Board, taking the first steps toward what would eventually amount to countless hours of public meetings, fundraising events, public and private partnerships, hundreds of volunteers, a Montana State Parks Recreational Trails Program grant, and 15 years of Land Board support.

In response, the Land Board chartered the 2004 Whitefish Area Trust Land Advisory Committee, which consisted of numerous local stakeholders, including the DNRC. The committee drafted the Whitefish Area Trust Lands Neighborhood Plan and over the next year brainstormed possible uses for the land, eventually settling on the creation of a permanent public recreation corridor that would encircle Whitefish Lake in the form of a series of connected trail networks and conservation easements.

The plan seeks out the best ways to manage and protect the lands while providing revenue for schools, and the nonprofit organization Whitefish Legacy Partners formed to demonstrate that outdoor recreation could be both an environmentally sound and financially productive use of the land.

Today, as the team at Whitefish Legacy Partners, led by Executive Director Heidi Van Everen, rolls out its plan to complete a network of community trails encircling Whitefish Lake and “close the loop” on the ambitious Whitefish Trail project, its earliest champions can’t help but look back at its humble beginnings.

“The genesis of the whole project was essentially conservation, back when Spencer Mountain was rumored to be on the chopping block for real estate development, and local trail network after local trail network seemed to be getting swallowed up,” said Costain, owner of Terraflow Trail Systems, and the architect of dozens of miles of single-track in the Flathead Valley and beyond. “Small-town Montana wasn’t necessarily aware of or well-versed in what land was private and what was public. There just seemed to be open land everywhere. It wasn’t until people realized they were set to lose something they’d been enjoying on a regular basis that it seemed critical to do something about it.”

An early advocate of the idea, Costain’s years of professional trail work has helped create large chunks of the Whitefish Trail system, the anchor project of Whitefish Legacy Partners, and the upshot of a community collaborative to preserve clean water, public access, recreation, and working forests.

As of this fall, the Whitefish Trail will feature 42 miles of trail, providing access at a dozen trailheads in and around town, and is poised to complete its next round of trail development in Haskill Basin, where 5.5 miles of trail will soon connect downtown Whitefish to Whitefish Mountain Resort on Big Mountain.

Another early proponent of the Whitefish Trail was Greg Gunderson, who in 2002 formed Forestoration, Inc. Trail Design, which has designed and constructed numerous sections of the Whitefish Trail, as well as trailhead kiosks, bathrooms and signage.

Gunderson was involved from the outset, joining the Whitefish Area Trust Land Advisory Committee and advocating for professionally built trails designed to accommodate a multitude of recreational uses while protecting wildlife corridors and still allowing for productive forest management.

“They stuck me on the committee and that was my first introduction to what state lands were all about,” Gunderson said. “I started my business with a goal of sustainable land management, and I came from a position of not wanting to see the state land sold off. Looking back, I didn’t really know what I was getting myself into.”

Since then, the roster of trail projects that have been proposed or come to fruition in the Flathead Valley has only grown, whether they entail buffed-out single-track through stands of Douglas fir, larch and Ponderosa, or asphalt paths connecting communities to Glacier National Park and Flathead Lake — the Foy’s to Blacktail Trail, the Glacier to Gateway Trail and the Rails to Trails project all stand out as success stories.

“Slowly but surely people started to understand that not only were these really fun trails, but presumably these lands are going to stay protected for generations,” Costain said. “It’s been so unbelievably rewarding to be involved with this from the get-go. I can’t even express it.”

Margosia Jadkowski, project manager at Whitefish Legacy Partners, said the ongoing support for outdoor recreation and conservation has helped keep vulnerable local lands accessible and undeveloped while also fulfilling the DNRC’s mission. The money is predominantly generated from land grants, private donations and easement purchases.

“This has paid over $19 million overall into state trust lands, and that is big money going towards schools,” Jadkowski said. “It shows that timber sales and grazing and mining aren’t the only ways to fulfill the mandate of state trust lands, and that recreation can be part of the equation.”

The trail system emerging on Haskill Basin is a good example of how Whitefish Legacy Partners takes care to minimize impacts to wildlife corridors by skimming existing developments like Iron Horse rather than piercing the heart of the forest.

“How we design and build the trail is focused on having the least amount of impact on the landscape, the ecosystem and the wildlife populations,” Jadkowski said.

Connecting people to the landscape also helps advance Whitefish Legacy Partners’ goal of shaping a paradigm shift that will help the state Land Board understand how the trail system can support recreation and compatible forestry, a concept hat has drawn skepticism in the past, but which the Whitefish Trail has proven can coexist.

“The bigger perspective of how we use recreation to promote conservation is about connecting people to the landscape in a personal way, and a trail is one of best ways to do that,” she said. “One of the best ways to create advocates for the conservation landscape is by having people connect with it personally.”

On Oct. 1, the Whitefish Legacy Run will provide an opportunity for the community to celebrate and connect with the trail system as runners participate in varying distances, ranging from a half marathon to a family fun run.

For more information or to donate, visit www.whitefishlegacy.org.

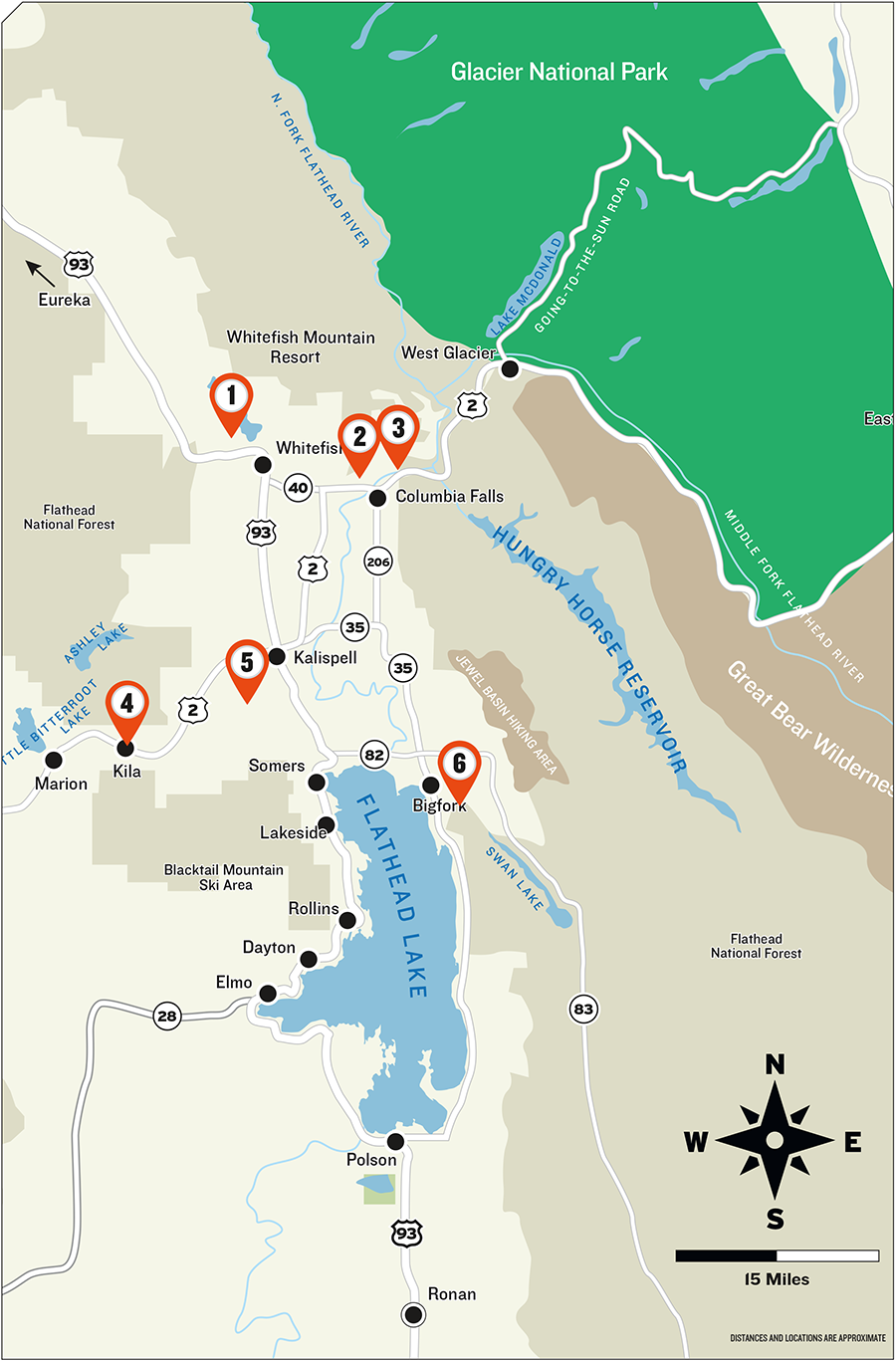

– Flathead Valley Trail Additions –

1. Whitefish Trails

Haskill Basin has been a treasured community resource for years, and the ongoing opportunities to recreate on its lands are a privilege allowed through a handshake deal with neighbors F.H. Stoltze Land and Lumber Company, the oldest family owned and operated private timber company in Montana.

Last year’s purchase of the 3,022-acre Haskill Basin conservation easement resulted in the removal of development rights, permanent protection of the city’s municipal water supply, continued sustainable management of the timber, and guaranteed recreation access.

Now, Whitefish Legacy Partners is in the midst of completing a new 5.5-mile portion of trail on the easement land, including a new Whitefish Trail trailhead at the water treatment plant on Reservoir Road, located just a half-mile from the paved bike path along Wisconsin Avenue, and another trailhead on Big Mountain Road.

For more information, visit www.whitefishlegacypartners.org.

2. Cedar Flats

Still in its infancy, a proposal to build a multi-use trail access north of Columbia Falls and connect the system with the community of Columbia Falls and nearby trail networks is gaining momentum.

Dovetailing with the efforts of the Gateway to Glacier Trail and working in concert with the U.S. Forest Service and Flathead County, Columbia Falls resident Jeremiah Martin has been hammering out a blueprint for the proposed trail system and gauging interest in the community.

While the “dream plan” involves 35 miles of trail, Martin said there will be upcoming opportunities for the public to be involved with the proposal.

3. Gateway to Glacier

The Gateway to Glacier Trail is the passion project of a local nonprofit organization whose mission is to connect Glacier National Park and Columbia Falls with a bicycle and pedestrian path, and which continues to make major strides toward completing its goal.

The first portion of the path is a 7-mile separated segment from Coram to West Glacier, and the group has successfully lobbied the Montana Department of Transportation to include a bike path from Hungry Horse through Bad Rock Canyon and across the South Fork Flathead River as part of the department’s planned highway upgrade.

In addition, the group has secured funding through the Federal Lands Access Program for a 2.7-mile trail from Columbia Falls to Bad Rock Canyon.

4. Rails To Trails

One of the valley’s original trail catalysts continues to thrive and stretch its reach.

Rails to Trails of Northwest Montana formed in the late 1980s after the Flathead County Parks Department planned to purchase the Burlington Northern right-of-way from Somers north to Highway 82 and transform it into a trail. The trail opened in 1998 and led to today’s system of trails that spans Somers to Kalispell and west to Kila.

This fall the finishing touches were made to a renovated section of trail in Kila that includes nearly 700 feet of new pavement and culverts near the post office.

Mark Crowley, president of Rails to Trails of Northwest Montana, said the renovated section provides a critical link for the entire system.

Rails to Trails of Northwest Montana is preparing to debut a new map that identifies all the valley’s trails. For more information about the organization, visit www.railstotrailsofnwmt.com.

5. Foys to Blacktail

After over a decade of work, community support and grassroots fundraising, the Foy’s to Blacktail Trail was finished this summer, with eight miles of newly built trail connecting Herron Park to Flathead National Forest lands to the south. The multi-use, non-motorized Foy’s to Blacktail Trail now traverses 18.8 miles from Herron Park to Blacktail Mountain above Lakeside.

The new section of trail has been open to the public since construction was completed in early August and is easy to follow for its entire length, though permanent signs and maps are not yet available.

Foy’s to Blacktail Trails, Inc., is the nonprofit stewardship partner of this trail and the trail system in Herron Park, and more information about the organization is available online at www.foystoblacktailtrails.org.

6. The Bigfork Trail

The century-old, two-mile Swan River Nature Trail near downtown Bigfork is a remnant of the main road linking the foothills of the Swan Range to the northeastern shore of Flathead Lake, and today the historic path is inspiring new visions for trail projects.

The initial vision — dubbed “The Bigfork Trail” — is to create a set of trail loops that would connect with existing and future trails on the north and south sides of the Swan River and tie into Sliter Park, downtown Bigfork and other nearby trails.

Paul Mutascio, president of the Community Foundation for a Better Bigfork, said ecotourism and outdoor recreation are becoming more and more popular, and the new trail system would benefit residents and businesses while also attracting visitors.

A small working group banded together last fall and began devising the preliminary project plan.