CHARLO — It all started with a headache.

During the third quarter of a Class C football game against Clark Fork Co-Op in Alberton, Charlo Vikings lineman Nick Daugherty started to feel nauseated. Maybe it was a cold, the 16-year-old sophomore with curly red hair thought to himself, or maybe it was the smoke from nearby wildfires.

After the game, Nick walked back to the team bus and fell asleep. When the bus pulled into the McDonald’s parking lot in Missoula for dinner, the entire team unloaded to get food. Nick stayed behind. When his head coach, Mike Krahn, asked what was wrong, the boy said he wasn’t hungry because he had a stomachache.

When the school bus got back to Charlo around 11 p.m., Nick walked across the parking lot to his green Ford Ranger and drove home, forgetting his bag on the bus.

The following morning, Nick told his mother, Lauren Holloway, that he had a headache. She asked if he was dehydrated and suggested he drink water.

That week at school, Nick had trouble paying attention in class. At football practice — which had been moved into the gymnasium because of the wildfire smoke that blanketed the state that first week of September — he had trouble remembering plays. He was forgetting so many that teammates teased him about it. “Are you with us, Nick?” one of his coaches asked during practice.

Despite his persistent headache and nauseous feeling in his stomach, Nick suited up to play on Sept. 11 against Arlee High School.

“It was the homecoming game,” Nick said. “I couldn’t miss it.”

A few minutes into the third quarter, an Arlee ball carrier cut across the field. Nick turned to follow the play. He had his head down when an offensive lineman struck him on the top of the head at full force. Nick fell backwards.

“I didn’t see the hit, but I heard it,” coach Krahn said.

After a teammate helped him up, Nick wobbled to the sideline. Krahn told him to see a trainer, who sat Nick on the bench and started to ask him questions: where he was, whom the Vikings were playing, what the score was. Nick shut his eyes and stopped talking. The trainer started to scream for a nearby EMT and Nick’s mother. By the time Holloway got to the bench, EMTs were cutting Nick’s jersey off and getting ready to put him on a stretcher. He was loaded onto an ambulance and taken to St. Luke Community Hospital in Ronan, where doctors confirmed what everyone already knew: Nick had suffered a severe concussion.

Every year, a quarter million people go to the emergency room following a concussion, and it’s estimated millions more go untreated or unnoticed. The Brain Injury Research Institute estimates that nearly 3.8 million sports and recreation-related concussions occur in the United States annually. Forty-seven percent of all youth sports concussions are the result of high school football, and the number of concussion-related emergency room visits among teenagers has doubled in the last decade.

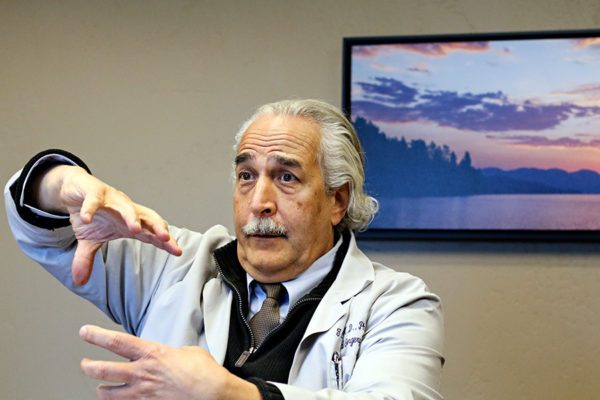

Dr. Thomas Origitano, a neurological surgeon at Kalispell Regional Healthcare, said concussions have become an “epidemic” in this country.

“It’s a matter of perception,” he said. “If I said millions of people were being sickened by a preventable disease, we would do something about it. We would stop it. We would all take that vaccine.”

A concussion is a type of traumatic brain injury caused by a blow to the head that results in the brain rapidly moving back and forth and slamming against the inner skull. It can cause headaches, confusion and loss of consciousness. Long-term effects of a severe concussion can include memory loss, losing the ability to speak, struggles with coordination and balance, and emotional issues. It can take weeks or months to recover from a concussion, and multiple concussions can result in permanent disability or even death.

After Nick arrived at St. Luke’s, doctors conducted a computed tomography scan, also known as a CT scan, to see if there was bleeding in the brain. Nick was then sent to Kalispell Regional Healthcare. The Sept. 11 trip was not the first time that someone in Nick’s family had gone to the hospital following a football-related concussion. In 2005, Nick’s older brother Zachary was taken to St. Luke’s for a concussion but went home later that night. Holloway thought back to that incident as she followed Nick to Kalispell.

“This time felt different,” Holloway said. “My instincts, my insides told me it was serious.”

Nick spent two days in the intensive-care unit and remained hospitalized for two weeks. For most of his time in the hospital, Nick was groggy and would only mumble words. Whenever he wanted his mother’s attention, he would softly repeat “ma ma ma.” He was also extremely sensitive to light and wore sunglasses inside the dimmed hospital room. The light hurt Nick so much that Holloway covered the closed window blinds with towels.

Doctors were dumbfounded by the severity of Nick’s injury, Holloway said. “All of them would look at me as if I was from Mars when I said this was Nick’s first concussion,” she recalled. But as time went on, as Nick began to speak again, he revealed that he had been feeling ill in the days before the hit during the Arlee game.

Football-related concussions have been making headlines in recent years. In 2009, a study funded by the National Football League found that former players were 19 times more likely than the general population to have dementia, Alzheimer’s or other memory-related diseases. The NFL later backtracked and claimed that its own study was flawed, but scientists at the time said there was a clear link between repeated concussions and Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy, or CTE. The degenerative brain disease is primarily found in athletes and others with a history of repetitive brain injuries. In July, the American Medical Association published a study that stated CTE was found in 99 percent of deceased NFL players’ brains that were donated to scientific research.

The long-term impact of concussions on youth athletes has also raised concerns. In 2013, the Montana Legislature passed the Dylan Steigers Act that required all school athletic programs to teach coaches, parents and students about the dangers of concussions and how to recognize the symptoms. Earlier this year, the law was expanded to all youth sports organizations.

The law is named after Dylan Steigers, a Missoula native who died in 2010 at age 21 one day after getting a concussion during a scrimmage while playing football for Eastern Oregon University.

Rep. Moffie Funk, D-Helena, introduced a bill this year to expand the Dylan Steigers Act and said it has received wide support, including from the Montana High School Association, the governing body of high school athletics in the state.

“We want to make sure that parents, students and coaches have the training they need to recognize a concussion and then take the appropriate steps,” she said.

In 2013, Kalispell Regional Healthcare launched the Save the Brain campaign to raise awareness about concussions. Dr. Rachel Zeider, a physical medicine and rehabilitation specialist with KRH’s Neuroscience and Spine Institute and the medical director of the Save the Brain program, said the mission of the campaign is to provide seminars and training to get the latest concussion research into the community. The program also provides physical and cognitive testing for youth athletes and others so that if they do experience a concussion, doctors know what their baseline abilities are.

“We don’t want to scare people from participating in sports,” Zeider said. “We just want to make sure kids are playing responsibly.”

Origitano said he believes the culture that surrounds youth athletics, one where players push themselves to the extremes regardless of injury, needs to change in America, and parents, coaches and students have to remember that, at the end of the day, football is just a game. If a student is injured, he or she should be taken out of the game immediately.

“The era of ‘oh, rub some dirt on it and get back out there’ needs to be over,” Origitano said. “That philosophy needs to go away.”

Nick came home from the hospital on Sept. 25. The only time he typically leaves his parents’ Charlo house is for physical, occupational and speech therapy sessions in nearby Ronan.

Last Thursday, Nick got up around 7 a.m. like he usually does now and did some of his therapy homework. The worksheets included word searches and puzzles that help him sharpen his skills and his mind. One sheet, featuring a block of random letters, required Nick to circle the alphabet from A to Z.

“It’s frustrating sometimes,” Nick said. “It should be so easy, but it’s so hard.”

Sometimes Nick speaks slow and methodically, as if he is searching for each word. Sometimes, while sitting in his parents’ living room, he just stares into space or looks down. Nick said the last two months have been hard and that he’s frequently bored, although he recently started playing the guitar and occasionally plays video games.

In a few days, Nick will return to school, although for the first few weeks he will have to work one on one with a tutor. He’s optimistic that he’ll be able to rejoin his classmates at the beginning of next semester.

“I’m very happy about going back,” he said. “I think I can catch up — I’ve just got to jump back into it.”

Nick will be missing some class time to go to therapy. At St. Luke’s, Nick is working with a physical therapist to regain his balance and control. He frequently has to brace himself against a wall or furniture to walk. The therapist started last week’s session by having Nick stand against a wall and then move his arms up and down. Later they moved into the center of the room, where Nick and the therapist tossed a ball back and forth. Every few minutes, the therapist asked him if he was feeling dizzy on a scale of one to 10. At the beginning of the exercise, Nick was at a two, but after a few minutes, he went to a four. When another patient started to walk on a nearby treadmill, the noise of the machine sent Nick to a five. The therapist then guided Nick into a dim, quiet room to rest. He later said that whenever he gets dizzy, it feels as if the room is spinning.

As Nick sat in silence staring at the wall, his mother and the therapist quietly discussed upcoming sessions and what the health insurance provider would and would not cover. After about five minutes, the therapist asked if Nick was ready to start working again. They started an exercise where Nick held his hand out and moved his head side to side. After a few sets, Nick began to lose energy.

“Are you tired?” the therapist asked.

Nick nodded slowly, and therapy was over for the day.

In the lobby, an older gentleman recognized Nick and his mother.

“What’s with the gimp walk?” the man asked, looking at Nick.

“He got a concussion playing football,” Holloway said.

“Ahhh,” the old man said. “Well, is he going to be playing next season?”

It’s unlikely that Nick will ever play football, or any contact sport, again. Doctors believe it will take Nick a year to fully recover from his concussion, and if he’s lucky, he might be able to run track.

Holloway wishes she had been told the week before Nick’s concussion during the game with Arlee that he had forgotten his bags on the bus or that he couldn’t remember plays. That information, combined with the knowledge of Nick’s headache the morning after the first game, could have revealed that he had a concussion.

Holloway thinks high school football needs to be made safer and that schools should provide better helmets. Football helmets that better absorb impacts are on the market but often cost hundreds of dollars.

“If we’re going to be spending hundreds of thousands of dollars renovating our football fields, we should be putting that same amount of money into the helmets our children wear,” she said.

Holloway hopes that her family’s experiences will help other parents, coaches and athletes take the threat of concussions seriously.

“We have to do something, because this should never happen to a child,” she said.

Krahn, Charlo’s head coach, said the episode has been “sobering.” In recent years, he has changed how he coaches his players and encourages them to use less force during practices. He also said that he is constantly reminding his players to keep their heads up while playing, and he hopes that they come to him if they are feeling the symptoms of a concussion. He said open lines of communication between players, coaches and parents are essential.

“I think football is changing,” he said. “(But an incident like this) makes you question things. There is part of me that thinks, ‘Whoa, is this really worth it?’ It’s a tough question because I love the game and I think it teaches kids valuable life lessons.”

What the future holds for Nick is unknown. Holloway sometimes chokes up when thinking about her son and the road ahead.

“I want him to heal; I want him to get stronger,” she said. “I just want to know that he’s going to be OK.”

Holloway said the one thing that hasn’t changed since Nick’s concussion is his personality. He is still the kind and loving boy she has always known.

Nick has had a lot of time to think about the concussion and how it’s changed him. Despite his struggles with walking and talking, Nick said he can still think clearly but has trouble conveying what’s on his mind. When asked what he’s learned from the experience, Nick has a simple response.

“Patience.”