On the morning of Sept. 16, 1913, workers at the Glacier Park Lodge scurried around the immense lobby putting the finishing touches on a banquet fit for a king. Three rows of white linen tables stretched nearly 200 feet through the lobby, surrounded by massive Douglas fir columns that had been erected just months earlier when the lodge was built on the southern edge of Glacier National Park. In a few hours, more than 350 people would descend on the site for what newspapers of the era dubbed as “one of the largest banquets ever held in the Northwest.”

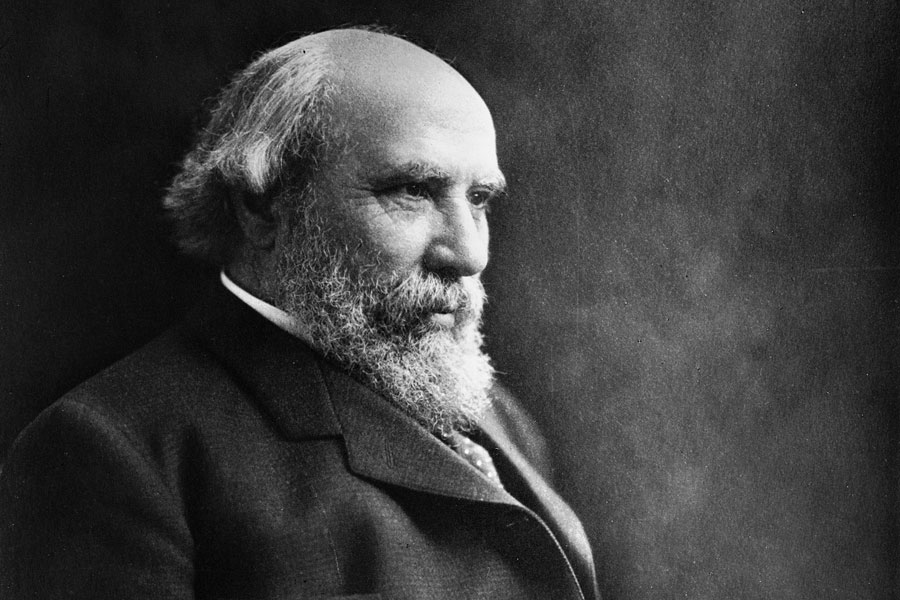

The fine china and pristine tablecloths had been unpacked in honor of one man: James J. Hill, who turned 75 that early autumn day 105 years ago.

For three decades, Hill was one of the most influential and imposing figures in the American Northwest. Hill rose from humble beginnings in Canada to become one of the most powerful businessmen in U.S. history, with his greatest accomplishment forever changing Northwest Montana and the Flathead Valley. The Great Northern Railway, completed 125 years ago this winter, helped Hill “become the single most powerful individual in the northwest United States,” according to author, historian and biographer Michael P. Malone. It also earned him a nickname forever etched into the history of this region: Empire Builder.

James J. Hill was born in 1838 in Ontario, Canada, the middle son of Scottish and Irish immigrants. Hill’s father, James Hill Sr., was a frontiersman and farmer who at times struggled to provide for his family; in later years Hill would recall being able to see the night sky through holes in the family home’s roof while he lay in bed. Hill and his younger brother Alexander had an upbringing typical of children growing up on the frontier, full of days spent hunting and fishing. When Hill was 9 years old, his love of hunting led to a tragic injury when a homemade bow snapped and lodged into his right eye. It had to be pried from the socket. A doctor was able to save the young man’s eyeball, but his vision on that side never fully recovered, and he could only see dark shades from that eye.

His parents had high hopes for their oldest son, and as a boy, Hill loved to read whatever he could get his hands on, including the Bible and Shakespeare. In 1848, Hill’s father purchased a roadside inn and moved the family to the community of Rockwood, Ontario. Four years later, Hill’s father suddenly passed away, and the young teen dropped out of school soon after to get a job to help the family. Hill worked at a general store where he earned a few dollars a week milking cows and keeping the books.

It was there that the young Hill had a chance meeting that would change his life forever. One day, Hill had watered a passing traveler’s horses without asking. The traveling trader from St. Paul, Minnesota took a liking to Hill and handed him a used newspaper with a story headlined “Splendid Chances for Young Men in the West.” As the man handed it to Hill, he mused, “Go out there, young man — that’s the place for you.” In 1856, Hill took the advice and moved to Minnesota. He got a job as a bookkeeper for one of the many shipping companies along the Mississippi River. His decision to move to St. Paul and find work within the shipping industry proved pivotal. He would spend the next 20 years rising through the ranks and becoming a prominent player in the shipping and coal industries.

In August 1867, Hill married Mary Theresa Mehegan, and the pair quickly went about having a family. In total, the couple had 10 children between 1868 and 1885.

Following the Civil War, railroad lines were being built to nearly every corner of the country, and trains quickly surpassed steamboats as the primary movers of freight in the United States. Hill perhaps saw the writing on the wall for his own industry and in the late 1870s began looking for ways to invest in railroads. Along with a group of investors, he eyed the Saint Paul and Pacific Railroad, which had been greatly impacted by a financial crisis called the Panic of 1873 and never fully rebounded. The railroad was purchased in 1879 and Hill was named general manager. Little did anyone know that Hill’s decision to enter the railroad industry would alter the course of history in the still-untamed Northwest.

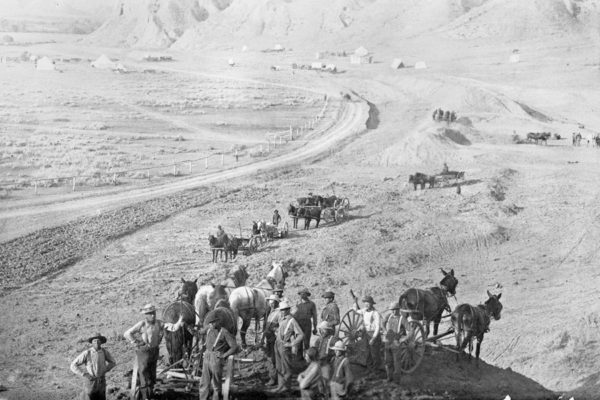

Over the next few years, Hill’s railroad would grow across Minnesota and into North Dakota. Hill was a hands-on manager and liked to spend most of his time at track-building camps “to be where the money was being spent” as the railroad expanded into the wilderness.

“Out in the field of western and northwestern Minnesota, Hill seemed to be everywhere, and the mystique of his dynamism now took form,” Malone wrote in his book, James J. Hill: Empire Builder of the Northwest. “He learned many of the men’s names and would walk along the grades calling out to them familiarly, even spelling them at their picks and shovels while they retired for a cup of hot coffee, a gesture he would employ for the rest of his career.”

But Hill wasn’t always a warm figure to his employees. The businessman was at times intense and difficult, especially with those closest to him at headquarters, where he prohibited coffee breaks. He would also frequently micromanage his workers and could be petty at times. According to legend, he once fired a station master because he didn’t like his name. On another occasion, after the residents of Wayzata, Minnesota had complained about the noise of passing trains at night, Hill moved the town’s station a mile down the tracks so residents had to walk even farther than before.

By the mid-1880s, Hill had become a millionaire. But while many of his contemporaries began to settle into more comfortable lifestyles, Hill refused to slow down. “You and I have got all we need and a great deal more besides, then what is the use of toiling and laboring night and day to increase it,” John S. Kennedy wrote to Hill, a close friend.

Hill wanted to expand his railroad west, and while many would say he was motivated by money, others could argue that he was instead driven by a desire to remain relevant within his industry. Smaller regional railroads that only connected a few communities were losing power to much larger, transcontinental operations that could move freight farther and cheaper. In order to survive, and thrive, Hill’s railroad needed to grow.

In 1887, tracklayers began to work west from Minot, North Dakota. Hill, ever the demanding railroad executive, wanted to have more than 640 miles of track laid in one year, extending his road to Havre in Montana, before turning south to Great Falls and Helena. It was an almost unimaginable goal, but in January laborers started shoving snow and clearing ground for track construction. By October, they had reached Great Falls, and a month later, they were knocking on Helena’s door. It was, by all accounts, a stunning achievement. Dudley Warner, co-author of The Gilded Age with Mark Twain, wrote later that the construction of more than 640 miles of track in one calendar year was “one of the most striking achievements of civilization.”

Hill spent much of 1888 and 1889 plotting his next move for extending his railroad across the Rocky Mountains to the Pacific Ocean. The simplest solution would have been to purchase the already-built Northern Pacific, which went through Butte, Helena and Missoula, on its way to Tacoma, Washington. At the time, the railroad, completed in 1883, was in dire financial shape and would have been an easy acquisition. But Hill thought he could do better by building a more direct railroad through the mountains west of Havre. The key to such a railroad would be finding the mysterious Marias Pass, rumored to be one of the lowest crossings of the Continental Divide in the United States.

While Hill considered how he should extend the railroad, he also renamed it: the Great Northern Railway. Hill had long been fascinated by a railroad in Great Britain of the same name and thought that it better matched his lofty goals to reach the Pacific Ocean. The name would last for more than 80 years.

In November 1889, Hill sent engineer John F. Stevens into the wilderness to find Marias Pass. Stevens would eventually become chief engineer on the Panama Canal, but in the 1880s, he primarily worked on railroads. Stevens arrived on the Blackfeet Reservation the following month and hired a local guide to take him to Marias Pass. Not long after the journey began, the guide fell ill and Stevens continued on alone. Eventually, he discovered a wide pass between the mountains where water flowed west: he had found the long-rumored crossing of the Northern Rockies. Stevens would spend a long, windy night alone at the summit — stomping in a circle to stay warm — before returning east the following morning to rescue his nearly dead guide and bring news of his discovery to Hill.

Come spring, tracklayers sprinted west toward Marias Pass. In September 1891, the rails summited the Continental Divide, and three months later, the rails arrived in Kalispell. The first Great Northern train rolled into downtown on Jan. 2, 1892 and was welcomed with a celebration that attracted thousands to witness the driving of a ceremonial silver spike. But the party didn’t last long as tracklayers quickly got back to work, laying rail down the Kootenai Valley and into Idaho and Washington. The final spike on the Great Northern’s line to the Pacific was pounded on Jan. 6, 1893 near Scenic, Washington, deep in the Cascade Mountains. The completed railway stretched 1,816 miles from St. Paul, Minnesota to Seattle.

Although the Great Northern had gone transcontinental, Hill wasn’t done building. He expanded his railroad north into southeastern British Columbia and south into Oregon.

Hill frequently traveled across the Great Northern and on occasion stopped in the Flathead Valley. Those stops almost always made headlines in Kalispell. According to historical newspaper clippings, the visits were almost always for business, and Hill would frequently meet with local leaders. But the visits were often brief. In May 1892, the Kalispell Commercial Club invited Hill to stop in town on his way to Spokane. The locals organized a banquet, but when Hill’s train was delayed, he decided to instead meet with them at the train station for a few hours before continuing west. A Daily Inter Lake story from 1899 discusses how Hill spent a day in the valley inspecting a site for a future railroad tie plant in Somers. The plant opened on the north end of Flathead Lake in 1901.

The notorious workaholic occasionally took time for rest and relaxation. According to an 1894 newspaper story, Hill and some business partners once “stopped off at Belton (today West Glacier) and ‘went fishin’.”

At the dawn of the 20th century, Hill began to hand off more control to his son, Louis, who had proven himself to be a talented businessman and railroader. In 1907, Hill retired as president but remained chairman of the board, a position he kept until 1912. Although he was relinquishing some control of his business, he stayed busy well into his 70s, spending a large part of his later years promoting development in the Northwest, particularly in agriculture.

In Hill’s mind, the more food farmers produced, the more they would need to ship freight on his railroad. The Great Northern frequently ran special exhibit trains to share the latest in agricultural technology and to promote different crops. The railroad also established experimental stations to try out new crops, including several in the Flathead Valley. Among the crops the GN encouraged in the Flathead Valley were French endive, celery and cherries.

According to Malone, Hill would tell almost anyone who would listen about the prospects of farming and agriculture in Montana. “The yields of most of the cereals (in Montana) are the highest per acre in the country. What she needs now is a larger population,” Hill once wrote. “It is upon the development of her agriculture that her future depends.”

Although there is no doubt that Hill was an industrialist, the railroad executive also realized that natural resources like timber were not infinite. According to Malone, Hill was a proponent of conservation efforts to save certain lands and resources.

In September 1913, Hill’s son Louis threw him a 75th birthday party at the Glacier Park Lodge. More than 350 people attended the gathering, many of them members of the Veterans’ Association of Great Northern Railway who had worked for the railroad at least 25 years, a prerequisite for joining. The event attracted a number of local dignitaries, including Montana’s governor, and was capped off with the presentation of 75 American Beauty roses to Hill.

Hill spent his twilight years in his adopted hometown of St. Paul, mostly focusing on philanthropic work. Hill died on May 29, 1916. He was 77 years old. Following the news of his death, flags were dropped to half-mast from St. Paul to Portland and tributes poured in from every corner of the nation. On the occasion of his passing, the Great Falls Tribune wrote, “The title of Mr. Hill to greatness is that he achieved great things in the way of making the world in which he lived a better place to live in. He made gardens grow where desert land existed before. He made available for habitations millions of homes where only gophers and wild animals before had their habitations. He added greatly to the sum total of human happiness.”

Hill’s railroad and business ventures also greatly padded his bank account. When he died in 1916, he was worth more than $52 million, or more than $1 billion in today’s money. It was the sum of a lifetime in which he helped shape an entire region of the country.

“He was without peer, the preeminent builder of the frontier economy of the Northwest,” Malone wrote.

In 1970, the Great Northern Railway merged with three other railroads to become Burlington Northern, the predecessor to BNSF Railway, a company that still plays a dominant role in the economy of Montana and the Pacific Northwest. Today, BNSF is one of the largest railroads in North America, stretching more than 32,000 miles across 28 states. In 2009, business magnate and investor Warren Buffett purchased the railroad for $44 billion.

Of all James J. Hill’s accomplishments, the construction of the Great Northern Railway was among his most cherished achievements. Hill made it obvious in a message he wrote on July 1, 1912, when he retired as chairman of the board.

“Most men who have really lived have had, in some shape, their great adventure,” he said. “This railway is mine.”

Read more of our best long-form journalism in Flathead Living. Pick up the spring edition for free on newsstands across the valley beginning March 15.