Work is expected to begin on a multi-million dollar wastewater project in Kalispell this spring that will simultaneously help alleviate an over-burdened sewage system and clear the way for continued development on the west side of town.

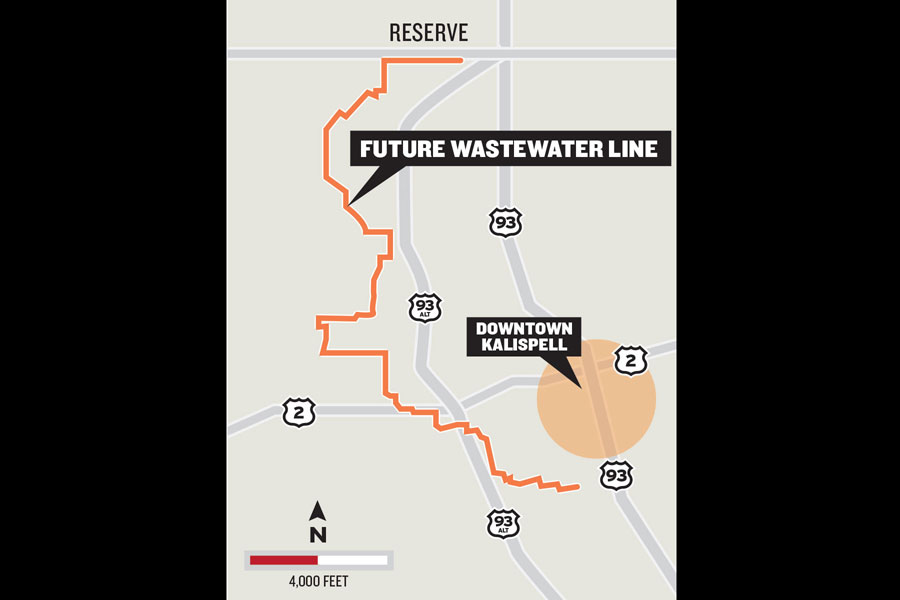

The West Side Interceptor Project has been on the Kalispell Public Works’ wish list for more than a decade and, after years of planning, the city is finally soliciting for bids from contractors. The project will see the construction of 45,000 feet of sewage main line from downtown Kalispell north to the intersection of U.S. Highway 93 and West Reserve Drive.

“This project is putting us in a great position for future growth,” said City Manager Doug Russell, adding that had the West Side Interceptor not already been in the planning stages the last few years’ development would have slowed to a trickle.

The West Side Interceptor is the largest public work’s project in Kalispell since the wastewater treatment plant was upgraded in 2009. When the project is completed this fall it is expected to have cost more than $10 million.

The new sewage main will provide service for about 4,936 acres on the northwest side of Kalispell, enough to support more than 17,600 households and 44,195 people. The project is being split into five sections so that different contractors can bid on it, although Public Works Director Susie Turner said any contractor can bid on one or all of the sections.

The first section connects with an existing 30-inch sewer main on 10th Street West, about two blocks south of Flathead High School, and runs west following Eighth Avenue West, Eighth Street West and Seventh Street West. The main will briefly run up South Meridian Road before traveling along the railroad right-of-way north before going under the U.S. Highway 93 bypass near Applewood Drive.

When the bypass was constructed in 2015, a section of sewer main was installed under the road in anticipation of the project. The second section of main will briefly follow the Great Northern Historical Trail before turning north under U.S. Highway 2, where contractors will have to tunnel underneath the highway as opposed to digging it up. The second section ends near Three Mile Drive.

Sections three and four travel through neighborhoods along Three Mile Drive and end near Glacier High School. And the final section runs from the roundabout just west of the high school under Old Reserve Drive to U.S. Highway 93 where it meets up with existing infrastructure.

About 34,000 feet of the project will be made up of gravity main and 11,000 feet of it will be forced main, which features a pumping system to move sewage up rises in the main. Turner said forced main often requires more maintenance and so it is only used when it absolutely necessary. The pipe will be on average about 4 feet deep in the ground, although there are points where it will be even deeper, including one location where it will be 28 feet below the surface.

Turner said construction is expected to begin in June and completed before Dec. 1. The project will result in a number of detours in town throughout the summer and fall, although Turner notes that among the requirements for contractors is to have the fewest number of streets closed as possible at any one time during the project.

“We want to make sure there is minimal inconvenience for the public,” she said.

The first four sections of the project – stretching from Eighth Avenue West all north to Old Reserve Drive near Glacier High – will most likely take place over the summer, whereas the final section will wait until autumn. Turner said the final section under Old Reserve can’t be built until it can be connected with the rest of the system, so she expects the eventual contractor will wait until September to work on that project.

While heavy construction will begin in the coming weeks, in many ways the hardest parts of the project completed for city officials. Turner said it has taken nearly a decade to plan and design the project, one of the largest the department has undertaken in recent history. The project required a dozen different permits, mostly from the Montana Department of Environmental Quality.

“There was a lot of work that went into this effort,” she said.