Winter held a paralyzing grip on northern Montana in late January and early February of 1950, locking the region in what officials called a “winter emergency,” with sub-zero temperatures, deep snow and howling winds.

For at least 500 miles across the state’s northern tier, deep drifts had blocked roads and crippled entire communities. Browning, just east of Glacier National Park on the Blackfeet Indian Reservation, was in the storm’s icy epicenter. U.S. Highway 2 was obstructed by snow to the east and west, and conditions were similar on U.S. 89, preventing travel north and south from the town.

County and state officials worked to reach people stranded across the isolated reservation, some for several weeks. State newspapers reported that U.S. Air Force cargo planes from the base in Great Falls were preparing “to bomb the Blackfeet reservation with food and clothing,’’ adding that flights overhead found conditions to be desolate and the plight of rural residents to be “pitiful.”

When coach Jess LaBuff and his basketball team boarded a westbound train near the end of the first week of February, the storm had finally waned, leaving behind drifts that reached second-story windows in Browning. The Great Northern rail line, intermittently closed due to heavy snow, had opened, allowing the team to board a train and take on Columbia Falls and Lincoln County High School in Eureka.

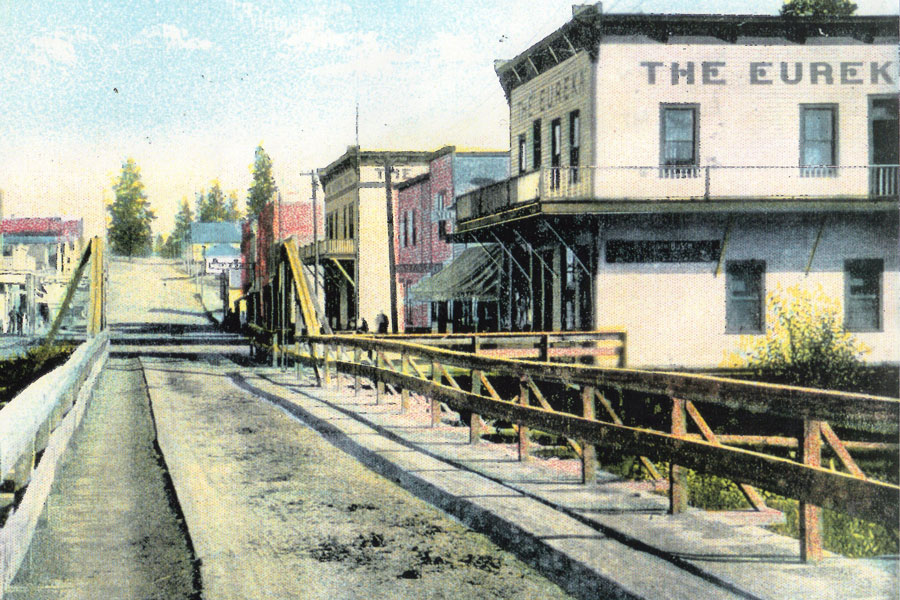

The Browning Indians lost to the Columbia Falls Wildcats 50-35 on Friday night, but bounced back on Saturday in Eureka, beating the Lions 49-48. A night in The Montana Hotel awaited the victorious visitors, who planned to catch the train back to Browning the next day.

The Montana Hotel, on the town’s main street, was a wood-framed, two-story structure and offered the best lodging in Eureka. Along with about 25 guest rooms, many on the second floor, the hotel included several apartments and the post office, which was reportedly home to the town’s sole telephone.

It had also been a tough winter in Eureka, about six miles from the Canadian border.

In December 1949, fire had destroyed the American Legion Hall. Just a few days before the weekend Eureka-Browning basketball game, another fire a half block from The Montana Hotel consumed three businesses — Bud’s Coffee Shop, Betty’s Beauty Shop and Hank’s Barbershop — on a night when temperatures bottomed out at 30 below zero. An overheated stove was the suspected cause. That same night, a local woman, Mary Pomeroy, died after being critically burned a day earlier when a furnace grate in her home caught her clothing on fire.

Early on Sunday, Feb. 5, 1950, as the Browning basketball team and others in The Montana Hotel slept, a furnace in the hotel exploded. Flames shot through the building. The hotel operator, L.A. “Larry” Riley, ran from an apartment he occupied with his wife and pounded on doors, trying to awaken sleeping guests.

On the second floor, Ronnie Norman, a member of the Browning team, was stretched across his bed at about 3 a.m., reading a magazine, when he heard a woman scream “fire.” According to an account in the Browning Chief, a weekly newspaper, Norman “rushed out of his room into the hall, which was dense with smoke, the atmosphere being suffocating” and pounded on nearby doors to roust his teammates.

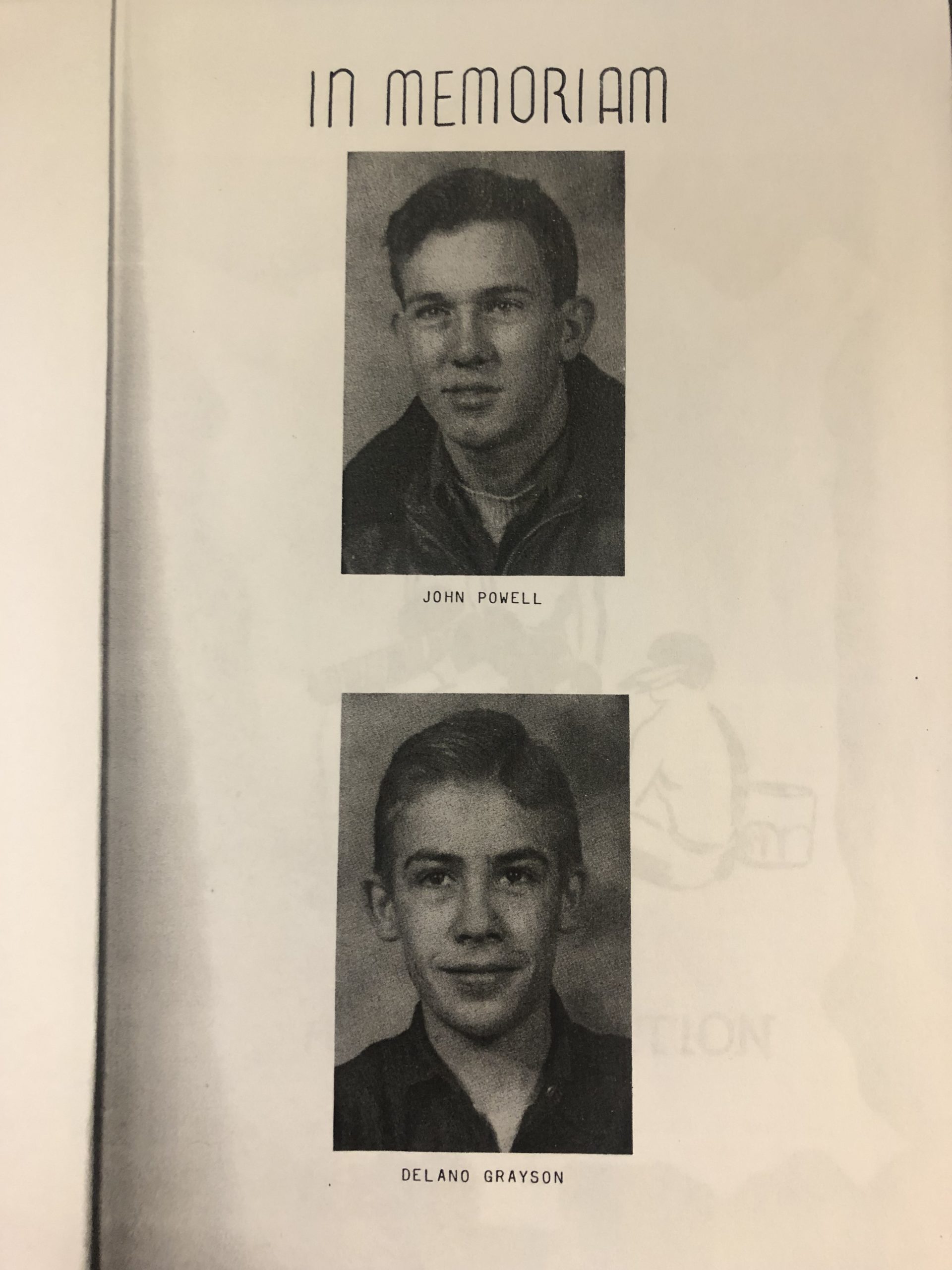

Norman, joined by Jimmie Lahr, another player, managed to wake their coach and all of their teammates, except two, Johnny Powell and Delano Grayson. Attempting to reach the room occupied by the two, Norman was driven back by intense smoke.

“All the others,” the Chief reported, “succeeded in making their escape, and occupying the second floor of the building, found themselves faced by a high jump out of windows. With the first floor a mass of flames, this was their only alternative.”

Possibly cushioned by deep piles of snow, only two team members, Roland Kennerly and Albert Flamand, were injured in the roughly 20-foot jump to the ground. Local residents, who gathered quickly to fight the fire, witnessed the boys, mostly in their night clothes, leaping to safety.

“Those who did not get out right away, did not get out at all,” an unidentified witness told the Daily Missoulian in a story published on Feb. 6, 1950. Shortly after the boys jumped, “the upper floors collapsed into the fire below.”

LaBuff, the Browning coach, credited his team with saving his life and likely others. The players “roused everyone possible in the few minutes before the whole place was in flames,” LaBuff said in the Daily Missoulian account. “They literally shoved me through a door and we jumped from the second-story window into the snow. If it had not been for the boys, I could never had gotten out.”

Local volunteer firefighters poured water on the blaze and, aided by local U.S. Forest Service employees, pumped water from the nearby Tobacco River. Sparks and debris flew to the roofs of nearby buildings. But witnesses credited deep snow and bitter cold from keeping the fire from spreading to other structures.

Local fire chief George Davis, who owned a nearby restaurant, arrived at the hotel shortly after the fire was reported. He said the structure was destroyed within a half hour. “I never saw a building burn so fast,” Davis told the Daily Inter Lake in Kalispell.

The fire not only consumed the hotel but the post office and its telephone. Also lost was the hotel’s guest registry, leaving firefighters and would-be rescuers unable to determine how many made it out alive.

A headcount on the Browning team yielded a sad answer: two from the team were missing — Powell, a junior guard, and Grayson, the team manager.

News of the fire and the missing boys was relayed to the reservation by a Great Northern operator, who was able to reach the Browning school superintendent at about 4:15 a.m. Word of the tragedy spread quickly.

As firefighters probed the smoldering structure, the Browning team moved to cabins elsewhere in town. LaBuff, the coach, stayed at the fire scene much of the day, harboring dim hope that the missing boys survived. That afternoon, the coach and his team boarded a train to head home. “I couldn’t stay here another night,” the coach said.

The bodies of Powell and Grayson were found later Sunday, along with those of three others: Ed LaFrance, 60, a clerk in the hotel, Charles Cameron, 60, a well-known local farmer and rancher, and William Peterson, 47, a railroad employee, possibly from Great Falls.

In the coming days, Eureka residents, including members of the basketball team, would travel to Browning for the funerals of Powell and Grayson. While Eureka didn’t have a community newspaper in 1950, the Feb. 24, 1950, issue of the Evergreen, the high school newspaper, published a letter to the Eureka community from Helen Kelly, the aunt of Johnny Powell, who wrote on behalf of the boy’s mother and other family members, many of whom lived in Babb, a community northwest of Browning.

“We hope that you all will understand how very much your kindness has meant to all of us,” she wrote. “Your town and school representatives at the funeral was only something that a town with a heart would think of. That one gesture gave more than you will ever know … My sister hopes that all the people who cared for our boys all day Sunday will know how very much their mothers want to see them, and in some way, show their appreciation.”

Powell was buried near his family home in Babb, with his teammates serving as pallbearers. An obituary in the Chief noted the 17-year-old’s love of football and basketball: “He had looked forward to the coming district tournament with pleasure and with determination to do his part towards winning the championship.”

Funeral services for Grayson, 16, were also held in Babb. A Boy Scout, he was described as a worthy and capable student who also “showed a high devotion to athletics.” An older brother, Gordon, had earlier played basketball for Browning.

The Powell and Grayson families published a note in the Chief about two weeks after the fire, thanking people on the reservation and in Eureka. “It seems that everyone in this community has found an individual and kindly means of showing us that our sorrow is shared,” they wrote. “If there is any alleviation of sorrow possible in an experience such as we have gone through, it would certainly be found in all this kindness.”

The Browning team finished in a second-place tie with Sunburst in regular season play and entered the district tournament, which was held in Browning in early March, with hopes of a championship. After winning games against Brady and Oilmont, the Indians lost to Valier 43-27 and finished third in the tournament.

Not long after losing their son, Grayson’s parents, who had operated a store, left the Blackfeet reservation.

LaBuff, the coach, born in Browning in 1919, left the reservation to take a teaching and coaching job in Shelby the next year. He died in 1973, at age 53. He was later inducted into the Montana Indian Athletic Hall of Fame and the Montana Coaches Association Hall of Fame.

A young Earl Old Person played basketball for Browning in 1949 with several members of the team that visited Eureka the following year. Seven decades later, Old Person, the chief of the Blackfeet Tribe, hasn’t forgotten the pall cast by the deaths.

“When that took place, it was a sad time for Browning,” Old Person said. “There are some that remember, but it’s been a long time.”

Butch Larcombe is a regular contributor to Flathead Living, the Beacon’s quarterly magazine. A version of this story will appear in a nonfiction book about Montana disasters to be published this spring by Farcountry Press in Helena.