The Ballot Battle

Flathead County has joined 45 other counties in opting for an all-mail election. Despite the controversy, and efforts to block the practice, election administrators say it’s safe and secure.

By Tristan Scott

On Sept. 3, following passage of a resolution authorizing Flathead County to conduct an all-mail election in November, County Commissioner Randy Brodehl consoled a group of crestfallen constituents outside his chambers.

“It’s not what I wanted,” he said, the mood having grown somber. “But I did what I could.”

Moments earlier, Brodehl cast the lone vote against allowing local election administrators to adopt an all-mail format, challenging his fellow commissioners to follow suit and “stand up to the outside pressures from the political machine.”

“Where do we stop if we don’t stop here?” Brodehl said, echoing the sentiments of a handful of residents who spoke out against a measure that most county governments across Montana had already adopted. “I am not going to allow the political machine to influence this process.”

Brodehl’s assertion that the county’s top leaders — all of them Republicans — were buckling to outside pressure prompted a sharp rebuke from fellow Commissioner Pam Holmquist, who said the decision was driven strictly by a desire to promote health and safety.

“I totally disagree with Randy’s opinion on this,” she said. “This is not and shouldn’t be anything to do with politics. This is about making sure that everyone has an opportunity to cast a ballot.”

Regardless of whether or not politics should enter the equation, politics has, and one of the biggest fights of this year’s presidential election has come to bear on the format of the election itself.

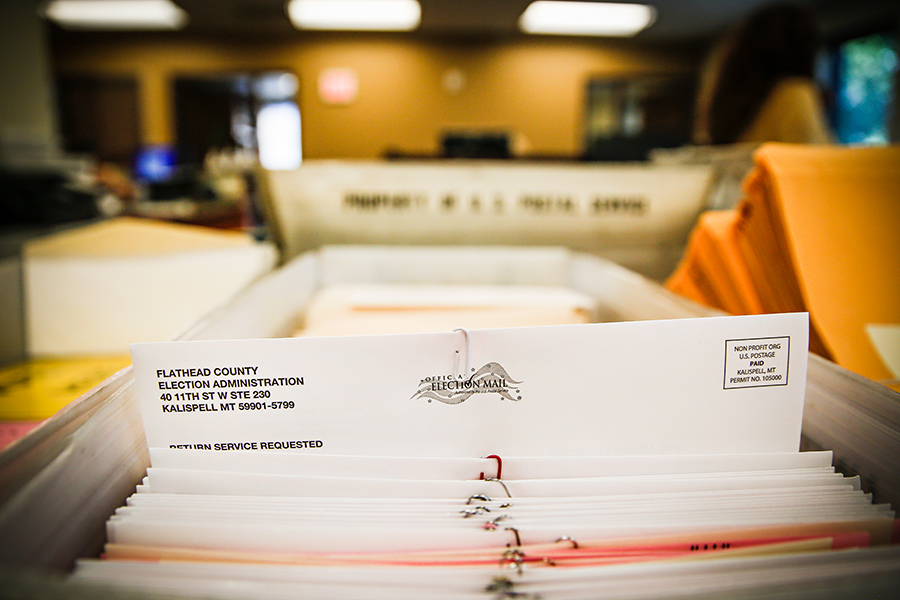

Citing public health concerns surrounding the pandemic, which complicated the logistics of opening in-person polling stations, 46 of the state’s 56 counties have opted for all-mail ballots for the statewide general election in November, the first time that’s ever happened in Montana history. That means local administrators will mail ballots to all registered voters on Oct. 9, and will continue mailing ballots to anyone who registers up to Oct. 26. Polling places will not be open on Election Day, although ballot drop-boxes will be available at certain locations in the Flathead Valley, and the Flathead County Election Department in Kalispell will be open and available for voters to hand deliver ballots.

In Montana, county governments were granted the option to hold mail-in elections in accordance with Democratic Gov. Steve Bullock’s Aug. 6 directive allowing them to individually decide how they will conduct their elections in November. A similar directive allowed for an all-mail primary election in June, when the entire state adopted that format and saw record voter turnout.

Citing that success and pointing to persistent public health concerns, county election officials and the Montana Association of Counties pressed Bullock to give them a similar degree of latitude leading up to the November election. State law says the general election must have polling stations open on Election Day, but Bullock used his emergency powers under the COVID-19 pandemic to grant counties the option of shifting to all-mail ballots.

However, Republican groups have filed two separate lawsuits to overturn Bullock’s directive, alleging that only the Montana Legislature has the authority to grant approval for an all-mail ballot election. One lawsuit lists President Donald Trump’s campaign as the plaintiff, as well as the Montana Republican Party, the Republican National Committee and the National Republican Senatorial Committee, and it names Bullock and Republican Secretary of State Corey Stapleton as the defendants. The second lawsuit, which has been merged procedurally with the first, was filed by a group of Republican voters, legislative candidates and the Ravalli County Republican Central Committee.

Both lawsuits accuse Bullock of using his authority to gain a tactical advantage in the election, and say mail ballots increase the potential for voter fraud and the disenfranchisement of voters.

According to local election officials, however, the controversy is rooted more in politics and perception than any problems with a mail-ballot system that has proven to be secure, and which continues to gain popularity every election season.

In Flathead County, more than 70% of its 72,094 registered voters (figure current as of Sept. 14) had already requested mail, or absentee, ballots for the general election prior to the shift to an all-mail election. Absentee voters have been increasing for more than a decade, according to Flathead County Election Manager Monica Eisenzimer, who acknowledges that while voters are slow to accept change, the ease of voting by mail has swayed many traditional voters.

A seasoned election administrator, Eisenzimer recalls when the Flathead was Montana’s largest county still using Votomatic-style punch-card ballots in its elections, the type that resulted in hanging chads and raised tough questions in the 2000 presidential race. When revising state election laws in 2003, in part to conform with the federal Help America Vote Act of 2002, the Montana Legislature passed a measure prohibiting punch-card ballots and specifying minimum technical requirements for any voting system certified by the secretary of state for use in Montana.

So perhaps it’s no surprise that the Flathead was the last of Montana’s major counties to adopt an all-mail election format in 2020, a year in which the coronavirus pandemic has made it more difficult to recruit volunteer election judges and secure polling places, which are often held inside schools. The pandemic has also invited political divisions into the election process, but election officials say that doesn’t have any influence on how they ensure security and accuracy.

“I don’t look at politics; I look at process. And our process is rock solid,” Eisenzimer said.

“Voting by mail is so simple and straightforward, but we haven’t wanted to force it because our voters in Flathead County are very traditional and they don’t like change,” Eisenzimer said.

Still, she said it’s frustrating to hear accusations of voter fraud and security breaches increasing due to mail-ballot elections, particularly as she oversees a department that employs multiple layers of security features.

To begin with, every active registered voter receives a ballot bearing a unique barcode that, when scanned, connects to a voter registration database of signatures. If the signature on the ballot envelope doesn’t match the signature on file in the database, the voter gets a call.

“If that signature doesn’t match the signature on the ballot envelope, we call the voter,” Eisenzimer said. “We don’t reject it outright, because we have had people change their signature, sometimes because of age or a medical issue. So we might call them and have them come in and provide a new one, but we verify it.”

Sometimes, Eisenzimer said spouses fill out one another’s ballot, and returns them bearing the incorrect signature.

“That happens more frequently than you’d think, but we just have them come in and get a replacement ballot,” she said.

And on several occasions, a voter has filled out a mail ballot and dropped it in the mail only to die before Election Day.

“You hear about dead people voting as evidence of voter fraud, but the only time it happens is if someone receives a ballot, votes and then dies,” Eisenzimer said. “That has happened and it makes me sad, but there’s something noble about how the last thing they did was cast their vote.”

Since Flathead County opted for an all-mail election, Eisenzimer said she’s been peppered with questions from voters about the bureaucratic nuts and bolts of the process; rather than view it as an annoyance, Eisenzimer said she’s delighted in informing voters about the process.

“We’ve been able to comfort a lot of people just by explaining how it works,” she said. “They have lots of questions, and we have the answers.”

She’s also developed a strong working relationship with the U.S. Postal Service, meeting regularly with Kalispell’s Bulk Mail Entry Unit Technician Jefferson Oxford to improve protocol for prioritizing mail ballots.

For starters, all of the ballot envelopes are bright pink, which “pretty much glow in the dark” amid a sea of white mail, Eisenzimer said.

“The postal workers treat ballots with the utmost importance,” she said.

Once, on the eve of a national election, a regional supervisor with the U.S. Postal Service was visiting the facilities in Missoula, which is home to the federal agency’s nearest mail-processing plant in Montana. He happened upon two Flathead County ballots and, rather than risk their late arrival, drove them to the Kalispell facility.

“That kind of tells you how conscientious they are about ballots,” Eisenzimer said.

Still, after every election, the Postal Service inevitably ends up with a tray of undelivered ballots that weren’t mailed on time, and voters should ensure they mail them on time or hand deliver them.

Even after receiving assurances about the security measures that render concerns over voter fraud moot, Flathead County’s two commissioners who ultimately approved the all-mail election said it was a difficult decision.

“This has been a difficult couple of days, probably some of the hardest since I have been commissioner,” Mitchell said prior to casting his vote, which marked a departure from the commission’s decision less than two weeks earlier to conduct in-person voting.

Part of that difficulty was reconciling the conflicting messages from voters urging an in-person election, political pressure from both major parties to conduct an all-mail election, and the fact that the directive allowing an all-mail option came from a Democratic governor running against a Republican in one of the nation’s tightest U.S. Senate races.

But Mitchell attributed his reversal to a COVID-19 outbreak at a Whitefish care facility that has killed 10 residents, and said after his initial vote he received 117 emails urging him to reconsider adopting an all-mail election format.

“I only received 11 asking for in-person polling,” Mitchell said. “So the ratio is 117 to 11.”

Ultimately, he said he couldn’t live with the thought that his actions might put some voters in harm’s way, or deter them from voting at all.

“I think everyone has the right to vote, even if they are still concerned about the coronavirus,” Mitchell continued. “Should I have thought about this a couple weeks ago when we discussed this? Yes, I probably should have. I don’t think I thought about it enough. You can hold me accountable for that. I will take the blame. But since then we have had more deaths and that’s what changed my mind.”

Still, a vocal minority of voters remain firmly entrenched in their opposition to an all-mail voting format, taking cues from President Trump, who warned in April that “you’d never have a Republican elected in this country again” if widespread mail voting was adopted, while some conservatives argue that expanding vote-by-mail is a liberal scheme.

“I totally oppose the mail-in ballots,” Susie Moore, of Whitefish, told the commissioners. “It opens up the possibility of fraud and this is probably the most important election that our country has ever faced. It is coming down to whether this country is going to be a socialist country or a free country. I was listening to one program where a woman received three ballots. This just opens it up to a very unfair election.”

However, there is no evidence showing that mail-ballot elections benefit a particular political party, and there has never been an instance of voter fraud in Flathead County.

Other opponents to all-mail voting said they rejected it as yet another unnecessary tactic to spread fear about a pandemic that has been “greatly exaggerated” in its scope — a point that Brodehl emphasized when casting his “no” vote on Sept. 3, and which resonated with his supporters.

“We need to stick to the constitution and not give in, especially now that we know this pandemic is less than previously believed,” Jolene Regier, of Kalispell, told the commissioners.

Others, like Scott Hefferman, volunteered to help staff polling places in the event of an in-person election, one of more than 200 people who asked to get trained as election judges this cycle, Eisenzimer said.

But Hefferman said he was pleased “that we have a system in place that works in a pandemic situation.”

“If it works and it’s effective, we should use it,” he said.

Eisenzimer said she’s not worried about any hiccups in the November election, but encouraged voters to make sure they’re registered and check that their status is active by going online to flathead.mt.gov/election and clicking on the “My Voter” page or by calling (406) 758-5535.

“We’re not the election police,” she said. “We’re not going to come find you. It’s your responsibility to vote.”