Editor’s Note: This story originally appeared in the summer 2016 edition of Flathead Living.

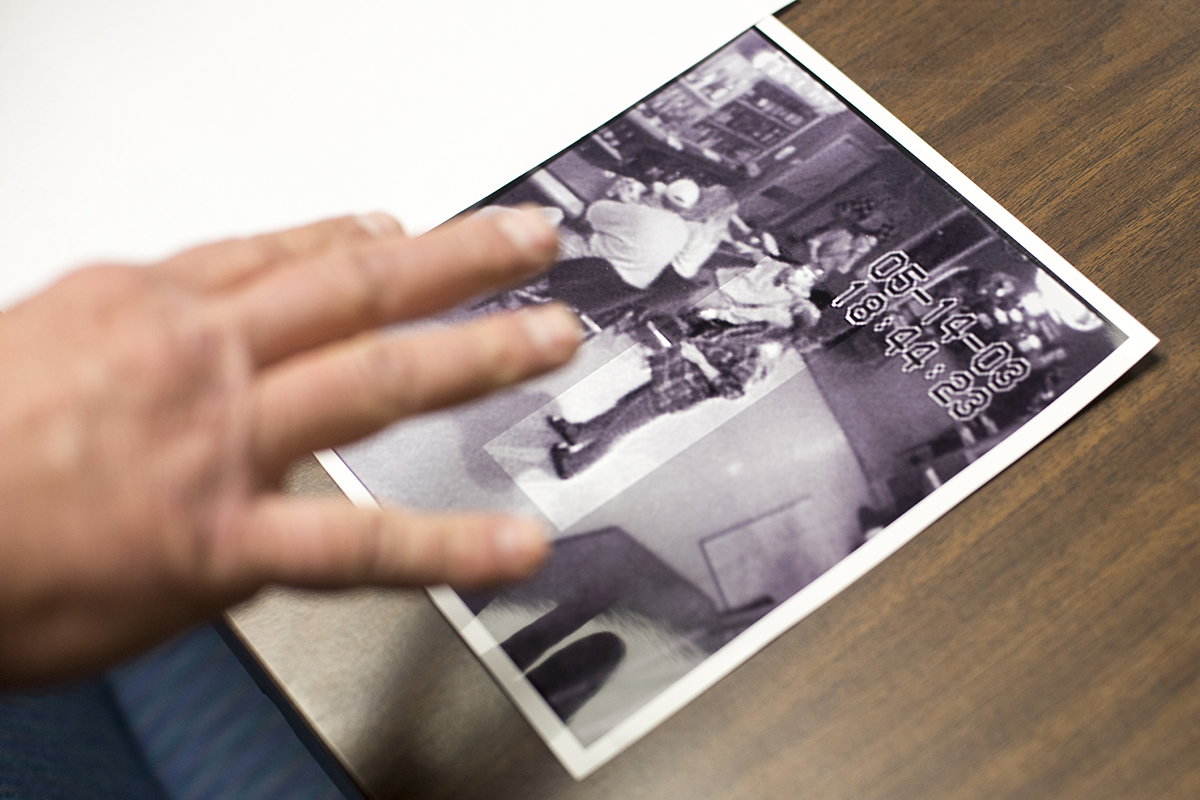

On the night Darlene Wilcock was murdered, in April 2003, she told her sister goodbye at their Kalispell home but didn’t say whom she was meeting. Security footage from the Finish Line bar later showed her, in separate frames, with each of the men considered primary persons of interest. When she arrived at Motel 6, where she was found naked and strangled to death early the next morning, cameras captured the 26-year-old checking in alone, neither man anywhere to be found.

One person of interest is her ex-fiancé, who wasn’t supposed to be in town that day. The other is a former roommate, a man she reportedly loathed. One man blatantly lied to investigators during subsequent interviews, while the other told a version of events that Wilcock’s family disputes. Thirteen years later, they both remain on the streets, unnamed publicly, even though authorities are positive one of them is the killer.

Absent of the other, each would be a clear-cut case for prosecutors. But together they represent a conundrum that has stumped both local investigators and FBI agents privy to the details, muddled by a complicated maze of circumstances that range from improbably coincidental to baffling. With the existence of the other, the alibi for each is as strong as the plausible guilt. Charge one and the other’s attorney now has a rock-solid defense.

For Wilcock’s family, Kalispell’s only unsolved murder has left them in a vacuum of uncertainty, where closure seems perhaps more distant now than in the weeks immediately following the slaying. For Kalispell Chief of Police Roger Nasset, the case remains the most troubling question mark of his long career in law enforcement.

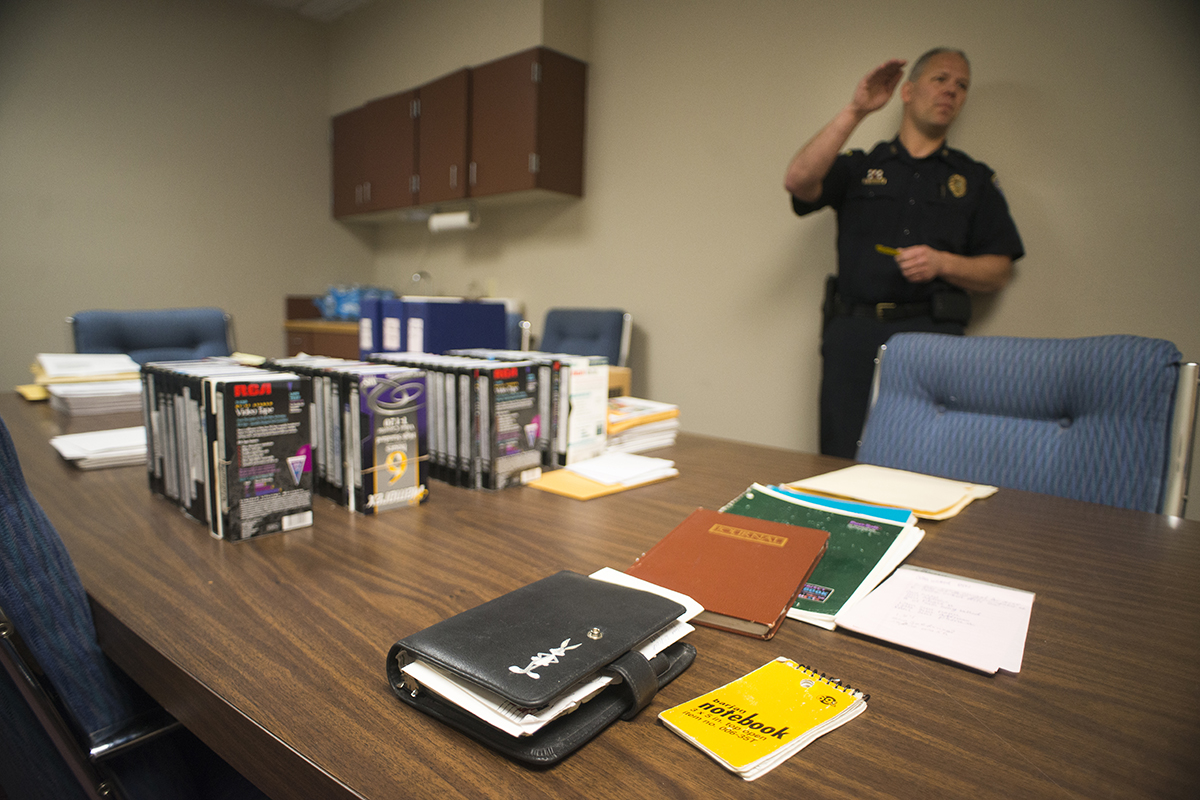

Earlier this year, a few days after the 13th anniversary of the homicide, Nasset stood over a conference room table buried underneath stacks of videos and file folders. The police department has a special section of its evidence room dedicated to the case, and Nasset had spread all of it out – minus the considerable physical items, such as clothes – to illustrate the scope of the investigation: a strong-willed lawman staring at a puzzle that has nearly broken his spirit. He clings to the hope that somehow, some way, the final pieces will arrive.

“It’s a burden weighing on my conscience,” Nasset said. “You don’t get rid of something like that. And that’s nothing compared to the family. I want closure for them.”

“We know we’ve spoken with the individual responsible,” he added.

Wilcock’s family continues walking the fine line between believing that answers will come and embracing the possibility that they never will, a kind of closure in itself. Holly Blouch, a sister, has taken the lead as the Wilcocks’ public face in the struggle for justice. She has conducted media interviews and reached out to national TV programs like America’s Most Wanted. She’s also raised community awareness through flyers and word of mouth, and done whatever else she can to keep her sister’s memory alive.

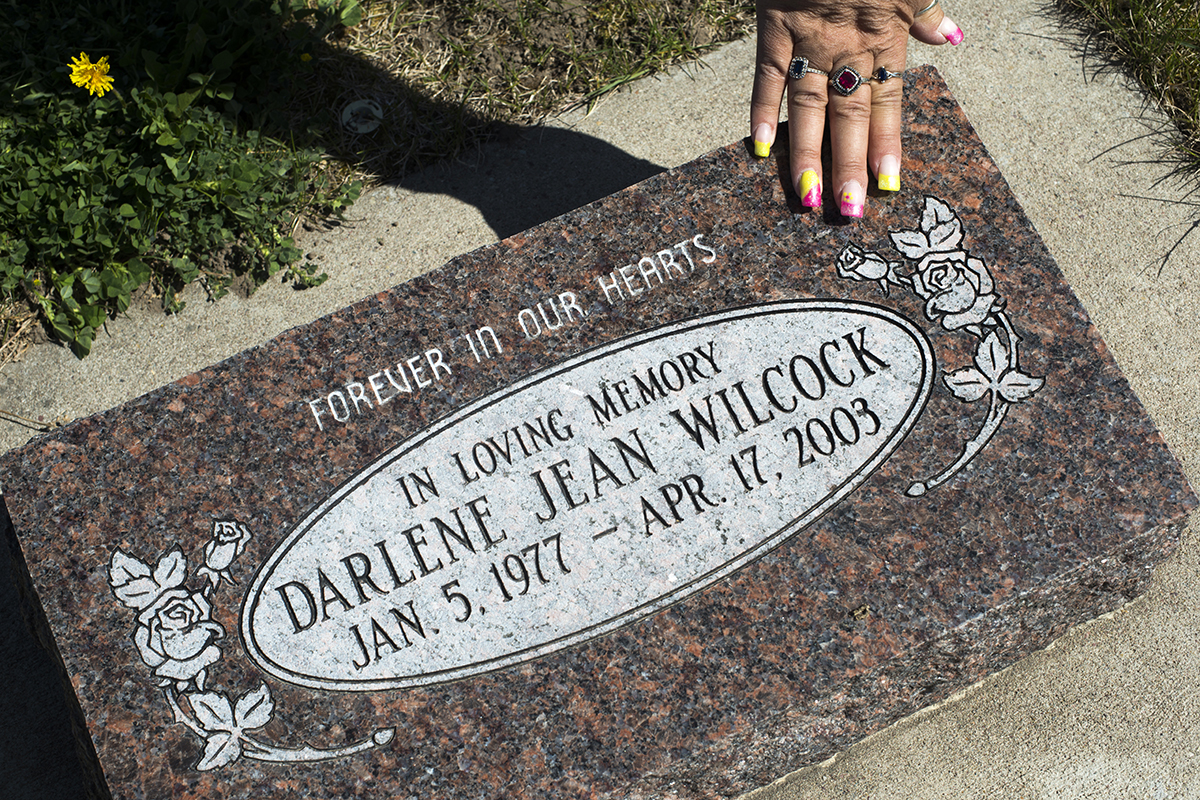

“Darlene was an amazing person who had a big heart,” Blouch said during an April visit to her sister’s grave in Polson. “She’d give you her last dime. She’d give you the shirt off her back. That’s just who she was.”

Brandi Bauer, the youngest Wilcock sibling, has fought a more private battle. Darlene was the most pivotal figure in her life, and the wounds sting as much today as when she first received news of the murder on her sister’s porch in Evergreen as a shell-shocked teenager.

“It would be nice to have an answer and get some closure,” Bauer says. “But we also have to think that it may never happen, and you have to move on with your life. You have to live for the living and remember the ones who are gone. There’s not much else you can do.”

The Wilcocks moved from California to Montana in 1996. They split their time between Kalispell and Rollins, where they had property on Flathead Lake. The beach there was Darlene’s favorite place to spend time. Darlene, the oldest of five siblings, was both a friend and mentor to her younger sisters and brother, especially to Brandi, the baby of the family.

“She was my mom, my best friend and my sister – she was everything,” Brandi says. “She was the one I went to talk to about everything: boys, friends, school, any trouble I was in, anything good that was happening. Anything that happened, she was the one I went to for advice.”

Darlene met her fiancé while working at Wendy’s and followed him on the road after he took a job truck driving. She eventually came back to the Flathead to work at Stream International. The fiancé continued pursuing a truck driving career, at least as far as the family knew. He was supposed to be out of town working on the night of her murder, though it later surfaced that he had returned to Kalispell but lied to authorities about it.

Those falsehoods, laid bare by the security camera footage, build a loose framework for a case against the fiancé. But the most damning evidence is a pair of $250,000 life insurance policies that he convinced Wilcock to take out shortly before the murder, naming him as the primary beneficiary. He also lied about being married to another woman.

Yet, his DNA wasn’t found on Wilcock or in the room. The other man’s was, as was the DNA of additional men. Coupled with the family’s claims that Wilcock despised the ex-roommate, and the footage of him at the bar, investigators have a second case just as strong as the first. But with no murder weapon and reasonable doubt both ways, neither case offers the proverbial smoking gun: physical evidence clearly linking either of them to the murder. Police haven’t uncovered any evidence of collusion between the two men.

The Kalispell Police Department has reassigned detectives to the case over the years, hoping that fresh eyes might shake something loose. But, short of a confession or a new tip, authorities can’t do much more. Nasset, who was one of the original detectives in the investigation, says the department has dedicated countless hours to solving the murder. He even presented it to the FBI Academy in Quantico, Virginia in 2006. They were equally confounded. In a city that averages .4 homicides per year, it’s the only unsolved murder Nasset has encountered in his 22 years with the department.

“We threw everything at this,” Nasset says. “This case was our life.”

Chris Yerkes, a private investigator hired by the family, has been working on the mystery, off and on, for nearly as long as the police. Like Nasset, he believes that somebody must know information that could solve everything. But that somebody hasn’t turned up – not a friend or an acquaintance or a barroom eavesdropper – and it’s been 13 years.

“In a community of this size, someone always knows something,” Yerkes says. “It’s one of those things where you kind of scratch your head and hope that someone does the right thing and comes forward. But barring that, there really aren’t any active leads, unfortunately.”

The former fiancé isn’t thought to be in the valley. At least for a while, he was a state employee in another town. The other man continues living in the Flathead and is now married. Blouch has photos of the fiancé, before he was named a primary person of interest, helping carry Wilcock’s casket at her funeral.

There was originally a third person of interest, Richard Dasen, Sr., the Kalispell businessman who was convicted of sex crimes in a widely publicized 2005 trial. Dasen’s DNA was found on room 233’s bedspread, although his DNA was discovered on numerous motel bedspreads around town because of his pervasive sexual activity.

Further complicating matters was the testimony of Kim Neise, who Dasen, Sr. paid to recruit young women and girls for sexual encounters. Neise claimed that Dasen, Sr. instructed her to bring up the Wilcock murder as an intimidation tool.

“I told them that’s what happens to girls who go to the police, is they end up dead,” Neise testified in court, according to a 2005 Missoulian article.

Perhaps Dasen, Sr. did use Wilcock’s death as an opportunity to intimidate women, but authorities don’t believe he was involved in the slaying. Nasset says there isn’t a shred of evidence suggesting any link between Wilcock and Dasen, Sr. Blouch, however, won’t dismiss the possibility of some connection. In a case where up often means down and left means right, she’s not willing to rule out anything.

Wilcock’s hilltop grave offers a stunning panorama of Flathead Lake, which was her favorite place in the world. With that view as a backdrop, Blouch, on her recent visit to the cemetery, thumbed through a memory book full of photos of the two sisters together, from toddlers to adults, grinning ear to ear. That’s how she will forever remember Darlene: happy, with the lake stretching into the distance, always smiling.