In 1998, Missoulian sports reporter Rial Cummings was looking through the paper’s microfilm archives when he came across a shocking photo.

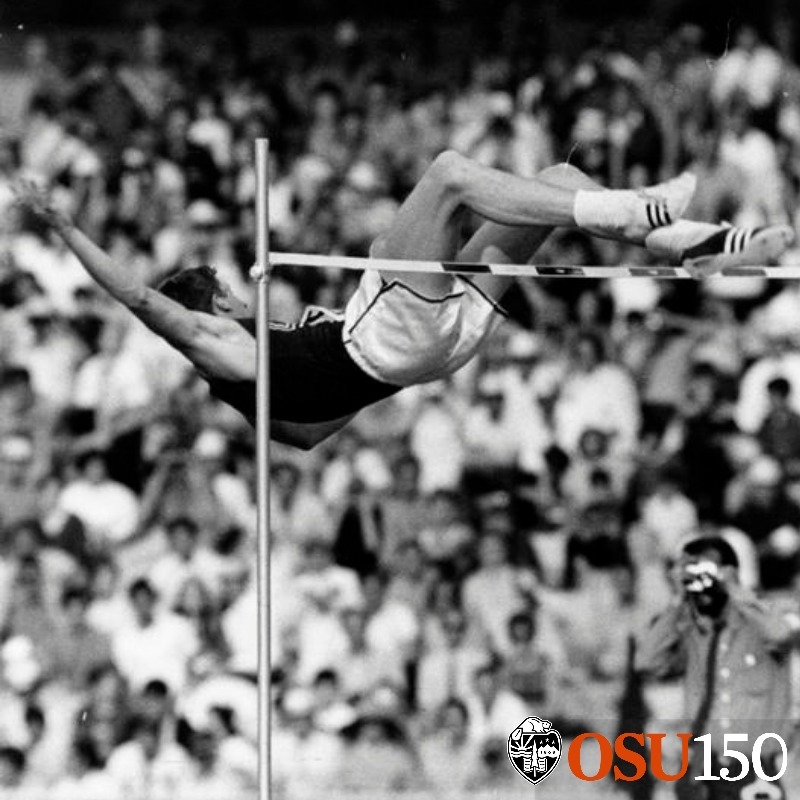

Tucked in the corner of a 1963 edition of the then Missoulian-Sentinel, separated from the rest of the paper’s coverage of the 57th Interscholastic track and field meet, is a blurry photo of a high jumper.

The photo itself is not that exceptional. The jumper is framed against the back of the University of Montana’s Main Hall, and his calf-high socks and Flathead County High School singlet stand out starkly in the black-and-white photo.

What is remarkable, and what Cummings noticed immediately, is that the jumper, senior Bruce Quande, was going over the bar backwards.

The caption to the photo “High Jumper in Reverse” states that Quande “hurled himself headfirst, on his back, over the bar,” but that “he didn’t do it often enough to finish in the money.”

Indeed, the results of the high jump competition a few pages further back in the paper list Jack Hyppa of Butte as the winner of the competition, at 6 feet 1 inch, followed by jumpers from Missoula, Helena and Billings Senior. There’s no mention of Flathead’s Quande.

Cummings had discovered that the modern technique used in high jumping, the Fosbury Flop, first displayed to the world at the 1968 Olympics when American Dick Fosbury bent backwards over the bar to set an Olympic record and win the gold medal, was used by an unknown boy from Kalispell years earlier.

“I always figured if you ran at the bar really hard, used a scissor and then a twist, you could [jump] better,” Quande, now 76, said in a recent interview. “It wasn’t rocket science.”

The Quande Conundrum

Bruce Quande lives in Missoula where he is semi-retired from his windshield repair business, but he grew up in the Flathead Valley when it was “pretty agrarian and pretty laid back.” He was initially raised on Third Avenue West before his family moved out to Northridge Heights.

“We literally caught, shot and raised everything we put on the table,” Quande said.

As a kid, Quande was always involved in sports, and water skiing was his number one passion, followed by downhill skiing, which he remembers doing on the slopes of Spencer.

Quande played basketball and flag football at Elrod Elementary, the start of his organized sporting career, and first set foot on the track in sixth grade.

“What my coach would do is throw you in different events depending on what facilities other schools had,” Quande recalled. “I think I did the 110, low hurdles, the 440 and long jump all in one meet. I scored 17 points all by myself.”

In high school, Quande began shifting toward the jumping events. At the time, high jumpers used one of two popular techniques to clear the bar: the scissor kick, where an athlete would run at the bar and take off straight up, throwing first the inside leg and then the other over the bar in a scissoring motion; or the western roll, where jumpers would take off with the leg closest to the bar, lay sideways along the bar as if lounging on a bed, and pass over it with the body parallel. Another version of the western roll, the straddle, had jumpers rotate their bodies so they faced the ground when passing over the bar.

Quande thinks he began experimenting with his own technique as early as his freshman year of high school in 1959.

“I thought if I doubled my runway, I could get more speed and that could somehow translate to jumping higher,” he said. “I always tell people it wasn’t that complicated.”

He used a modified scissor technique, running at the bar as fast as he could, lifting his inside leg and rotating away from the bar while throwing his head backwards over the bar.

The landing pits for high jump and pole vault at the time consisted of huge piles of sawdust, which worked since the common techniques allowed jumpers to land on their feet. With Quande’s style though, he had to land on his back, neck or shoulder, making his new technique a high-cost, potentially high-reward tradeoff.

Pioneering a new style of jumping was outlandish, to say the least. At the time, the Montana state record was 6 feet 6.5 inches, set in 1960 by Flathead County High School’s Mike Huggins, using the western roll.

“All those guys did the roll, and I would try the roll,” Quande recalled. “My coaches wanted me to use it and I had a little success with it, but then when I missed the bar I would go back to flopping.”

Quande thinks that he jumped 6 feet 2 inches his senior year of high school, albeit in practice, and was good enough to compete at the state meet, where he made an impression on his competitors.

“I thought he was insane,” said Jack Hyppa, winner of the 1963 Interscholastic meet. “Bruce was the first time I saw someone flop and I didn’t see how he could ever be successful at it.”

Hyppa used the traditional western roll and won every track meet he entered that year. His winning jump at state was 6 feet 1 inch.

Quande, on the other hand, was unable to match his best practice jumps at the state competition, and was relegated to a photo in the paper, several pages removed from the official results list.

“When Bruce was doing it, I just don’t think anyone understood what he was doing,” Hyppa said.

The Flop

Attend any high school track meet these days, or tune into the 2020 Tokyo Olympic Games next week, and only one style of high jumping will be seen.

However, it isn’t the Quande Curl that commentators will talk about, and high school coaches won’t tell tales of the state track meet in Missoula to freshman athletes. Instead, they will reference the man who put the most popular style of high jumping on the map: Dick Fosbury.

Fosbury grew up in Oregon, and as a high school track athlete he began experimenting with different ways to approach clearing the bar.

As a high school sophomore in 1963, Fosbury had middling success in the event, when one day he figured out that by leaning his shoulders back while doing the scissor kick he could lift his hips over the bar, and suddenly boosted his best height by six inches.

Fosbury benefited from his high school being an early adopter of foam landing pits, so he was able to flop safely (for the most part — he did compress his vertebrae a few times while perfecting the technique).

As a high school senior, Fosbury finished second at the Oregon state meet, clearing 6 feet 5 inches.

An Oregon paper ran a photo of Fosbury in high school captioned “Fosbury Flops Over Bar,” and the alliterative name began to stick.

He matriculated to Oregon State University to study engineering, and after his track coach initially tried to retrain him to use more traditional jumping methods, his flop was considered a success when he shattered the school record.

Fosbury’s Flop saw a meteoric rise in popularity in 1968 when he won the NCAA national championships, the first of two back-to-back titles.

Fresh off that win, Fosbury competed at the U.S. Olympic trials, winning easily, and then won a second trials competition held at an impromptu state-of-the-art Olympic training camp built at South Lake Tahoe.

In a weird twist of fate, Quande happened to be in Lake Tahoe during the Olympic training camp, but he didn’t watch the high jump competition, and never saw Fosbury flop. Instead he remembers playing flag football with three Olympic sprinters: fellow Montanan Larry Questad, Charles Greene and John Carlos, one of the Olympians known for giving the Black Power Salute on the medal stand.

In the high jump competition at the 1968 Olympic Games, Fosbury, fellow American Ed Caruthers and Soviet Union athlete Valentin Gevrilov were the only three jumpers to clear 7 feet 2.5 inches. Gevrilov missed all three attempts at the next height, and when the bar was raised to 7 feet 4.25 inches, a U.S. and Olympic record, Fosbury, utilizing his flop on the world’s biggest stage, won the gold medal.

For all of Fosbury’s headlines, and the style that carries his name, he was only one of the successful athletes experimenting with the high jump. Around the same time, another youngster independently evolved the flopping form as well. Debbie Brill, a 16-year-old Canadian, began experimenting with her form in a foam jumping pit her father built in their back yard to great success.

Using what the Canadian sports media dubbed the “Brill Bend,” she became the first North American woman to clear six feet in 1969, and went on to set an indoor world record in the 1980s.

Most histories of the sport talk at length about Fosbury’s revolutionary technique and Brill’s parallel innovative style, but Quande is relegated to a mere asterisk, if anything.

After the Jump

“I never saw anyone else jump like me,” Quande said.

After high school, Quande attended St. Olaf College in Minnesota for a year and was a member of the freshman track team. He continued working on his new style of jumping, and says he may have cleared 6 feet 5 inches at one point.

“I kept working at it, but it was hit and miss,” he recalled. “As you know, consistency is key in these events.”

Eventually, Quande stopped jumping after seeing a doctor who told him that after years of landing on his shoulder and back, he might start to get permanent damage. Quande gave it some serious thought and stepped away from the track.

He returned to Montana, enrolling at the University of Montana as a marketing student. He followed that up with a short stint in the U.S. Army and then a master’s degree at UM, where his thesis involved working with Ed Schenk to figure out how Big Mountain in Whitefish could compete with Sun Valley as the premier ski destination in the Northern Rockies.

As a sports fanatic, Quande always tuned into the Olympics but says he doesn’t recall when he first saw the world’s best jumpers using the flop. He does know that getting rid of the sawdust piles was essential to mainstreaming the style.

“Between when I jumped and they jumped, the foam pads came in and it made all the difference in the world for high jump and pole vault,” Quande said. “You could bounce when you landed.”

It wasn’t until the Missoulian reporter contacted him in the late ‘90s that he put it together that he may have been the first.

“They substantiated that I was definitely the first documented guy,” Quande said, mentioning interviews he did with Sports Illustrated and Track and Field News when the old photo surfaced. “Sometimes I look back and quite frankly think I should have stuck with it more.”

Ron Jones, a longtime high jump coach at Hellgate High School in Missoula, remembers mentions of Quande in conversations between coaches as they shared ideas about the evolving style of jumping.

“Somewhere over the years of talking with [Flathead coach Bill] Epperly it came up how Quande was exploring a new way of jumping back in the day,” Jones said. “He was ahead of the game with the flop.”

Jones has spent decades coaching high school track and field, and has taught athletes how to jump with all the major techniques over the decades — the western roll, the straddle and the flop.

“I started coaching in 1965, and once Fosbury put it up at the Olympics, everybody just started switching how we taught jumping,” he said. “The flop is really just speed. They mastered the jump with speed.”

Since Fosbury’s 1968 Olympic win, 34 of the next 36 Olympic medalists used the Flop, and it is the only style seen on the competitive stage today.

“It’s interesting, the Flop hasn’t changed very much since it was invented,” Jones said. “It’s based on speed and whether Bruce is doing it in the 60s or we’re doing it in the 2020s, it hasn’t changed much.”

“Bruce had the right idea, and where he picked it all up, I don’t know,” Jones continued. “But if you round off the sharp corners from what he was doing, you get to where we are today.”

The high jump competition at the 2020 Tokyo Olympic Games begins on July 29 for the men and Aug. 4 for the women. The current world record for the high jump was set in 1993 at 8 feet, ½ inch (2.45 meters) by Javier Sotomayor. For a great visual guide to the evolution of jumping techniques and Fosbury’s Olympic feat, watch this clip.