As Pressure Mounts on Private Timber Companies to Convert Forestland for Development, Many in Northwest Montana Choose to Conserve

Calling this an ‘apex moment’ for land use in the intermountain west, private timber interests and public land trusts have joined forces to conserve hundreds of thousands of forested acres

By Tristan Scott

If the growing scrum of land and development interests bearing down on the intermountain west were to attend a formal gala, the region’s swaths of privately owned forestlands would surely stand out as the belle of the ball.

And yet, as America’s working forestlands endure an unprecedented degree of pressure to convert their traditional bases to non-forest uses, including by subdividing parcels for trophy homes, many private timber companies in Northwest Montana and Idaho would prefer to remain a wallflower.

“There has been an enormous demographic shift where people are flocking to the mountains and we are getting routine, unsolicited offers for our timberlands on a weekly if not a daily basis,” said Barry Dexter, director of resources at Stimson Lumber Company, which owns hundreds of thousands of forested acres spanning northwest Montana, northern Idaho and northeastern Washington. “So the pressures to sell these lands are immense, and they’re growing more and more acute. But we’re in the business of growing trees, and our private timberlands are the foundation of our business. We want to keep producing timber and maintain our land for public access and open space. We don’t want to sell it off so developers can keep building McMansions. But right now everyone wants a piece of it.”

Still, even as a privately held company, Stimson is responsible to shareholders, which is why Dexter says the company’s partnerships with land trust organizations have never been more critical, particularly as it enters into agreements to furnish protections on its parcels, allowing continued forest management while safeguarding fish and wildlife species, staving off the threat of wildfire and maintaining public recreation access.

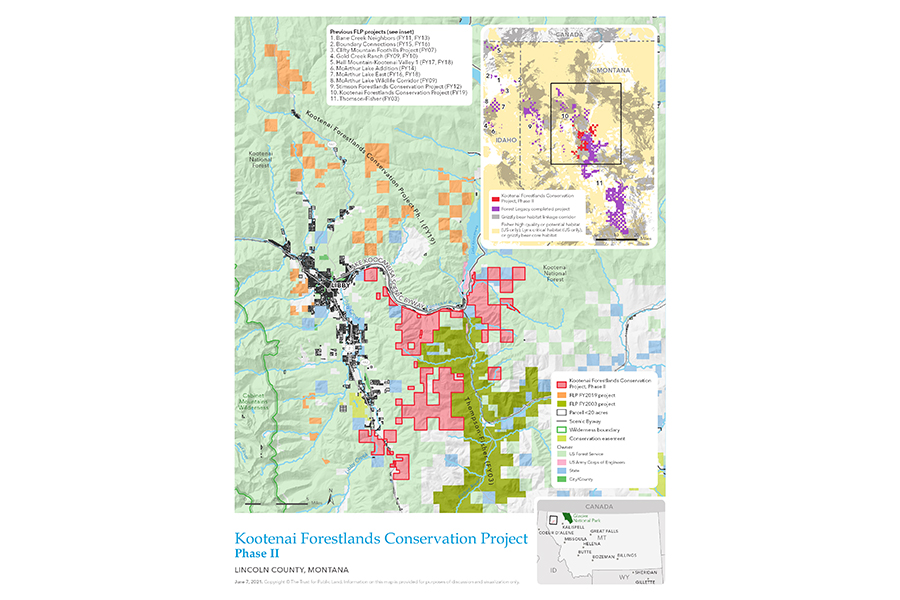

“If you look at a map of western Montana and see that checkerboard pattern of ownership, it’s mostly a sea of federal land with islands of private timberland,” Dexter said. “And with the unwinding of this landscape and its traditional uses, and as private land is sold off to different entities, we think it’s critically important that we keep as much of this landscape intact and available to the public as possible.”

To that end, Dexter is carefully tracking a “reconciliation bill” making its way through the U.S. House of Representatives, where the House Agriculture Committee has included $40 billion of investments in forestry provisions, including an historic $1.25 billion allocation over 10 years for the Forest Legacy Program (FLP), which has protected roughly 3 million acres of forestland across the U.S., including 268,000 acres in Montana. Established by Congress in 1990 and administered by the U.S. Forest Service, the FLP assists states and private forest owners in maintaining working landscapes through permanent conservation easements and fee acquisitions.

The reconciliation bill also earmarks $100 million for the Community Forest and Open Space Program, which help communities invest in natural infrastructure by conserving forests that sequester carbon dioxide and protect drinking water supplies, reducing the need for costly filtration and treatment systems.

The program has helped place conservation easements on nearly 100,000 acres of Stimson forestland, guaranteeing public access, preventing unchecked development and ensuring it remains productive for future generations, Dexter said.

“Conserving working forest lands contributes significantly to local and state economies, especially in rural areas,” Dexter said, noting that the National Alliance of Forest Owners reports that U.S. forests support approximately 2.5 million jobs, a $109 billion payroll and $288 billion in sales.

Jim Williams, regional supervisor for Montana Fish, Wildlife and Parks in northwest Montana, said programs like FLP, as well as Habitat Montana and the Montana Fish and Wildlife Conservation Trust, have helped maintain not only a viable timber industry in the Treasure State, but has preserved untold outdoor recreational access.

“There’s no program in the history of fish and wildlife conservation in Montana that comes close to the Forest Legacy Program in terms of the impact it’s had on maintaining a working landscape, maintaining public recreation access, and protecting critical fish and wildlife connectivity,” Williams said. “And we have been fortunate to work with willing timber companies as well as extremely knowledgeable land trust organizations that are the foremost experts on these partnerships.”

As senior project manager at The Trust for Public Land (TPL), Chris Deming has helped facilitate numerous deals between private companies like Stimson, the state of Montana and TPL, including pending “working forest” conservation easements of about 200,000 acres of timberlands reaching from Glacier National Park to the Cabinet Mountains Wilderness, as well as the Selkirks and Idaho Panhandle.

In addition to striking deals with Stimson, TPL has also worked with Southern Pine Plantations (SPP), a Georgia-based land investment company that purchased 630,000 acres in Northwest Montana from Weyerhaeuser in early 2020, and Green Diamond Resource Company, which purchased large swaths of the land from SPP.

Deming gives most of the credit for recent conservation successes to the private timber interests that have been willing to partner on conservation easements during what he calls “an apex moment” in the history of land use and conservation.

“These companies are being partially paid and they are partially donating the development rights of their timberland so they can move forward and say, ‘We don’t want the distraction of these unsolicited offers from developers,’” Deming explained. “That’s critical. It’s because of those decisions that we are able to keep these working forests on the landscape, keep development pressures at bay and continue to allow public access.”

Neil Ewald, Green Diamond’s senior vice president and chief operating officer, who has worked with TPL to conserve tens of thousands of acres on its newly acquired parcels, said the conservation easements allow his company to maintain the forests as a “generational asset,” providing a revenue stream while the forests produce more and healthier timber that can be harvested decades from now.

“There’s a saying that there are two income streams from forestry — income for today and value for tomorrow,” Ewald said. “Well, we’re not desperate for income today. We don’t have any big notes to pay off. But we think we can maximize the value for the future.”