Lost to the Lake

The Columbia River Treaty is heralded as a model for international trans-boundary water cooperation, but for some in Lincoln County it brings back painful memories of the community they lost

By Justin Franz

The sonar image on Dale White’s boat usually depicts what you would expect when he’s fishing on Lake Koocanusa: the lake bottom, rocks and hopefully a few fish waiting to tug on his line.

But sometimes something else comes across the screen: rubble from foundations, old concrete stairs and outlines of streets. The same streets he ran down as a kid.

White, 69, is a retired logger who spends his summers as a U.S. Forest Service campground host in Rexford. During the summer, he spends his days answering guests’ questions and making sure everyone is having a good time. But if you linger by his camper and ask him a few questions about what was there before Lake Koocanusa, a smile will undoubtedly cross his face as he talks about the old days, when Rexford was a busy little logging and railroad town.

White’s family had a small farm near Rexford and his dad helped run the town water supply. White said the farm would probably be considered a “hobby farm” today, but there was nothing recreational about it back then, and White and his siblings always had work to do. Yet they still found time for play, White recalls.

“The valley had everything a young boy could want,” White said. “Great fishing and great hunting.”

Talk to any old-timer along the Kootenai and they’ll say the same thing.

“I can’t even really describe what that old river valley was like,” said Bill Marvil, 72, who was born in Rexford, just like his father was. “It was beautiful.”

But a half-century ago, that lush valley was quite literally wiped off the face of the earth. In the 1970s, 90 miles of the Kootenai River from Libby north into Canada was flooded following the construction of the Libby Dam. The same thing happened north of the border in British Columbia, where three other dams were constructed as part of the Columbia River Treaty, a major trans-boundary water agreement between the United States and Canada. But there’s one major difference between what happened north of the border and what happened south of it — British Columbia is being compensated for the land it lost. Lincoln County is not.

Now American and Canadian officials are discussing ways to improve the agreement, and residents in Lincoln County are asking for some sort of reparation in a renegotiated Columbia River Treaty.

“We gave up more than anybody,” White said. “Lincoln County should get something for that.”

Rexford is a town that has never been able to sit still.

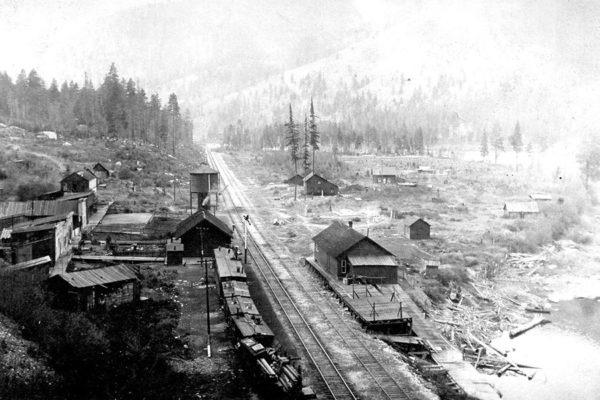

A community first cropped up on the banks of the Kootenai in that area back in the early 1900s. Speculators had purchased a plot of land there because they believed that was where the soon-to-be-built Great Northern Railway would pass through, and they figured it would be a good way to make a buck. But they had guessed wrong, and the railroad ended up bypassing the town by a mile. The speculators quickly purchased another 40 acres along the tracks and moved Rexford up the hill.

Despite Rexford’s modest size, it was an important spot on the railroad because locomotives had to stop there to take on water. As the railroad started to haul more freight and passengers — and more loggers began to harvest timber in the nearby hills — Rexford grew at a rapid pace. Within a few years, it had a railroad depot, a general store, a school and a church. But despite those amenities, Rexford was still a rugged little town, as witnessed in the 1920s by Frank McCarty, whose observations local historian Darris Flanagan reprinted in a book about the town.

“The dusty streets were crossed by barefooted boys, girls in boy’s shoes, Bill Resigue in his big black cowboy hat, and, occasionally, by horses and horse-drawn vehicles and, less often by Chevrolets, Stars, Moons, Buicks, Model T’s, and Fewkes’ great air-cooled Franklin,” McCarty wrote.

That’s the same type of town White, Marvil and Richard Payton all remember growing up in.

“It was a busy little place,” Payton said.

But the Rexford of Payton’s youth was not long for the world. In the 1940s, news came that the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers wanted to construct a dam north of Libby and turn the river valley north of there into a 370-foot deep reservoir. For decades, the Kootenai River Valley, and much of the Columbia River Basin, was ravaged with spring floods. One of the most notable happened in Vanport, Oregon in 1948 and killed more than 30 people. After that, the United States and Canada began to look for a solution and drafted the Columbia River Treaty, which proposed constructing four massive dams in the basin — one in the United States and three in Canada — to simultaneously control water flows and produce massive amounts of hydro-electricity.

The treaty was heralded as a model for trans-boundary water cooperation that would drastically improve the lives of those who lived along the Kootenai. The treaty came as welcome news to just about everyone except those who lived in places like Rexford.

“We had no choice,” Payton said. “They were going to take your land away one way or another.”

In the late 1960s, representatives from the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers began showing up in Rexford to discuss the benefits the dam would bring to the area, particularly in regards to recreation. According to Payton, they also told residents to not worry about maintaining their homes. After all, the Corps was going to be taking them down in a few years.

But when the Corps actually started negotiating with residents to buy their homes and property, it did not go as planned. The Corps would appraise each building and piece of property and then usually offer the lowest price possible. Some people took the Corps to court, but after all the legal bills, they usually ended up getting the same amount of money in the end. Marvil’s father, who owned a large ranch, thought he could make some extra money by selling gravel that was on his land. The Corps looked at it and said it was too dirty and couldn’t be used for anything. The Marvils took what they could get and left. Not long after, dump trucks were busy harvesting gravel from their property. White’s family had about 8 acres along the river, including a productive orchard, but the most they could get from the government was $7,000.

“The Corps are the bad guys to a lot of people in Rexford,” Payton said.

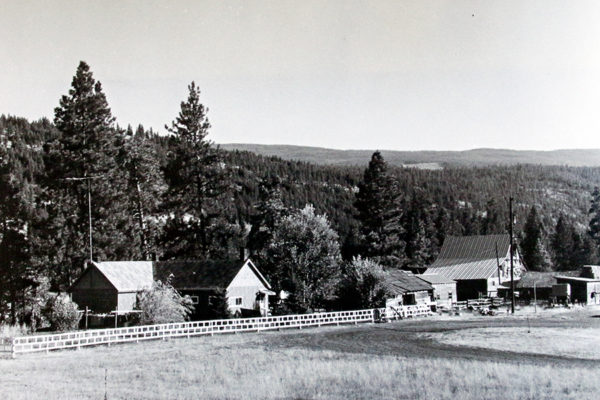

In the late 1960s, Rexford incorporated in a last ditch effort to survive. The government agreed to let the town move to a new plot of land closer to Eureka, but other Northwest Montana towns like Warland, Tweed, Ural, Volcour and Yarnell disappeared from the map.

Every time a home was sold to the Corps in the valley, bulldozers would tear down the structure before the remains were set on fire. Some buildings were moved up the hill to the new Rexford town site, while others, including the church, the general store and the railroad depot, were moved to Eureka. Today, all three buildings are preserved at the Tobacco Valley Historical Village.

While buildings were disappearing from the valley one by one, loggers were clear-cutting extensively. By the time the Libby Dam was completed in 1972 and the reservoir started to fill, the once-lush river valley had been scraped down to bedrock.

“It was strange to see all that water fill in (the valley),” Payton said.

Payton ended up trading his land in old Rexford for a lot at the new town site, where he still lives today.

Marvil left Rexford in the late 1960s for a two-year stint in the U.S. Army. When he returned, his hometown was gone, and his family, frustrated with their dealings with the federal government, had moved north to Canada. Marvil decided to put down roots in new Rexford. Today, he’s mayor of the small town.

“I was like any kid — I wanted to get out of my hometown. But when I did leave, all I ever wanted was to go home,” he said. “But when I came back, there was no home to go to.”

White ended up moving closer to Eureka. He said even if the new Rexford shared a name with the old town, it wasn’t the same.

“It’s a totally different town,” White said of today’s Rexford. “You can move buildings … but you can’t move an atmosphere.”

Today, you can drive down to the water’s edge on Black Lake Road and see where Rexford once was. Some years, when the water is really low, an old set of stairs from a building appears on the shore, but otherwise you would never know there was a town there at one time. The new town of Rexford is much smaller than its predecessor, more of a neighborhood than a community, although it does have a bar and a post office. The school closed years ago; today students go to Eureka.

In the late 1960s and early 1970s, when the Corps was talking up the benefits of a reservoir to Lincoln County, they highlighted the many recreational opportunities the body of water would bring. While there’s no denying Lake Koocanusa is a great place to go boating, it’s also home to the occasional dust storm in the spring when the reservoir is low. White said it’s sometimes impossible to see across the water.

Other local residents argue the recreational opportunities do little to offset what was lost to the lake, including prime timber and agricultural land. One of the county’s largest taxpayers, the railroad, also had to move its rail line, meaning there was less in the local coffers.

“I think we got the shaft,” Payton said.

Montana state Sen. Mike Cuffe hopes that past wrongs can be righted during the ongoing treaty negotiations. The Eureka Republican has been an outspoken voice in trying to get the government to recognize what the community lost. Cuffe convinced representatives from the U.S. Department of State — the agency that is holding treaty talks with Canada — to hold a town hall meeting in Kalispell in March.

Officials have declined to publicly say if some sort of payment to Lincoln County is in the cards, although they are seriously looking at changing how Canada is compensated. The 1964 treaty called for a one-time payment equal to half of the downstream power generated in the U.S. for 30 years. The payment of $254 million worth of electricity helped Canada build its three treaty dams. That part of the agreement expired in 2003, and since then the U.S. has delivered a daily allotment of power to Canada, worth $222 million to $359 million annually, known as the Canadian Entitlement. The money is directly deposited into British Columbia’s general fund.

American and Canadian officials are expected to meet in Washington D.C. for another round of negotiations in June.

During the March town hall meeting, the public made a number of suggestions to negotiators about how they would like to be compensated for what was lost a half-century ago. Some said they would like to see the money go directly to Lincoln County, while others said it should be used to fight aquatic invasive species.

White said he would like to see the money go toward improving recreational opportunities on Lake Koocanusa, including adding more boat docks and launches.

But White said a few extra boat launches wouldn’t be enough to replace what was lost.

“I’m not bitter,” he said. “I just wish we had our river back.”