A Living Museum

For more than eight decades, Glacier Park Boat Co. has taken painstaking care to ensure its heritage is on display with its fleet of historic wooden boats

By Tristan Scott

Each summer, thousands of visitors experience the majesty of Glacier National Park from atop the emerald-hued surface of Lake McDonald — just as the park’s earliest tourists did — by boarding the 56-foot oak-framed, cedar-planked DeSmet for a scenic boat cruise.

Every day from mid-May to late September, the historic vessel ferries passengers across Glacier’s largest lake, charting a course through the heart of the peak-studded McDonald Valley, where stands of western red cedar and hemlock mingle with Douglas fir around a fjord-like basin 10 miles in length and a mile wide, its burnished bottom-stones glittering beneath a halo of mountains.

This year, the DeSmet launched for its 89th season on Lake McDonald, plying the glacial waters that serve as a lifeblood, keeping the great wooden boat afloat while forcing it to contemplate a perennial inner struggle to stave off rot while simultaneously retaining enough moisture to maintain its structural integrity.

In nearly 90 years, the DeSmet has never left its home on Lake McDonald, and each winter it slumbers in the historic Fish Creek Bay boathouse at the foot of the lake, braving harsh winds and heavy snow and ice from within the cramped and dusty quarters, a custom-built and timber-framed fortress that has stood the test of time.

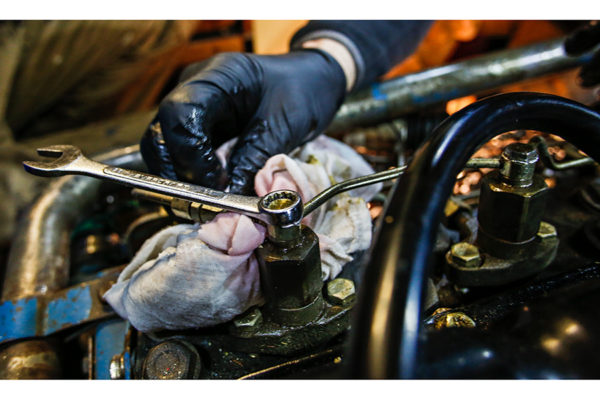

The boat becomes its most dignified self — and certainly its most visible self — during the summer months while cutting across Lake McDonald al fresco, its deck brimming with smiling passengers. But the intimate work of its caretaking occurs before and after the DeSmet emerges from the backcountry boathouse, under the lambent glow of workshop lights as a small band of fastidious boatmen massage new planks and materials into its aging hull, and make dozens of other complicated and unforeseen repairs as needed.

Like most of Glacier’s boathouses, the home of the DeSmet was constructed with the specific boat in mind, and each autumn the vessel is hauled in from the choppy waters on a cradle-track-and-winch system and returned to its confines. The crew shuts its doors tightly for protection from the elements, including the crashing of waves, and then returns every spring to inspect both the boat and boathouse, rapping on every plank in the hull with a mallet to listen for weaknesses that could indicate rot, a process know as “sounding the hull.”

As the flagship vessel in Glacier Park Boat Co.’s fleet, the DeSmet, like all the boats, commands a high degree of deference from the crew assigned to its care, and Scott Burch possesses a keen understanding of how to instill such respect in his workers — the boats each have a soul, he says, and “their fate is in your hands.”

Burch is the owner of Glacier Park Boat Co., the son of its previous owner Arthur M. Burch and the grandson of its founder Arthur J. Burch. As such, he knows everything there is to know about the company’s six boats and how to maintain their original splendor while toiling away in remote, unheated boathouses in unpredictable weather under unforgiving circumstances.

“We don’t do submarines or airplanes,” Burch said. “But we do everything else.”

Glacier Park Boat Co. has held the concession contract to operate the boats for recreational purposes in Glacier National Park since 1938, purchasing the fleet from Captain J.W. Swanson of Kalispell, a prolific boat builder who constructed many of Glacier’s historic boats, including four of the current vessels — the Sinopah on Two Medicine Lake, Little Chief on Saint Mary Lake, DeSmet on Lake McDonald, and Morning Eagle on Josephine Lake. (Swanson also built the M.V. International on Waterton Lake.)

Swanson sold the contract so he could attend to his ailing wife, and in announcing the sale to the elder Burch and another Kalispell businessman named Carl Anderson in a letter to Superintendent E.T. Scoyen, he lamented: “I am recommending Mr. Arthur Burch and Carl Anderson who are planning on taking over my interests and carry on the boat operation in about the same agreement as I have had in the past with the National Park Service. I personally regret leaving the Park as I have had the pleasure of helping to develop the boat business and wish the new owners all the success that you can extend them.”

Burch and Anderson initially paid $25,000 to buy out the contract and associated boats, boathouses and other equipment, while Swanson assisted them through the first summer in 1938. The newly renamed Glacier Park Boat Company has operated continually under the same family ever since.

For the first time, however, that contract is up for renegotiation this year with the National Park Service, and Burch and his loyal crew had laments of their own as they launched the DeSmet on Lake McDonald for what could possibly be its final voyage.

“The work that we do on this boat, all these boats, is exactly like the work that was done 90 years ago,” Burch said. “As long as someone is willing to repair these boats in what is essentially a wilderness setting, they could be around forever. Sure, another company could come along and replace them. But they would have no soul. They would have no character. It would be a whole lot easier. But the boats would have no personality.”

The complicated work of launching the DeSmet was on full display in early May as Burch and his six-man crew, led by longtime operations head Tyrel Johnson, prepared the boat for its 89th voyage from their “office” at the boathouse, which sports striking views of Dragon’s Tail. The labor involves donning wetsuits and snorkeling gear and using the winch-and-cradle outfit to guide the boat along rails that lead out into the depths of the lake, navigating any hitches in the system until the boat is afloat.

This follows days of flooding the hull with a watering hose so that the planks expand and become watertight, at least enough to ensure a summer’s worth of solvency.

Then there’s troubleshooting the diesel engine, which replaced the original gasoline engine to comply with National Park Service contractual standards to reduce the risk of combustion.

Just as pieces of the DeSmet have been replaced and repaired through the years, so too has the 1930 boathouse been modified, but the work is still “old school,” according to Burch and Johnson, the latter of whom has become an expert at surface-planing locally harvested red cedar boards, steaming and cutting and curving the 18-foot planks to size, and transforming them “from a two-dimensional board to a plank on a three-dimensional boat,” he says.

“I don’t know how many planks I’ve replaced on the DeSmet,” says Johnson, who’s been with the boat company for 14 years, even sleeping on the boat when wildfire threatened to overcome it.

Other year-round employees with intimate knowledge of the boats include Scott’s son Sam, Ben Anthony, Sam Wagner, JT Dolores, and Mitch Edling.

“You have to be a jack-of-all trades,” Scott Burch said. “It’s not just the boats we’re working on. It’s the docks and boathouses and other structures.”

To that end, Burch is constantly mentoring his employees in the finer points of boat building and maintenance, as well as imbuing the company’s rich history on his students.

Three of the boats have been added to the National Register of Historic Places, a recognition that came after years of work by the company’s interpretive manager James Hackethorn. The boats added to the registry include the Little Chief, the Sinopah and the DeSmet.

The Rising Wolf and Little Chief were both named after prominent geographical features near the lakes they served. Hackethorn said over the years, the boats have been moved for maintenance and have ended up in different lakes.

Because of those moves, both boats now carry different names; the Rising Wolf is now the Little Chief and the Little Chief is now the Sinopah. Other than the name changes, Hackethorn said the boats still appear as they did in the 1930s.

“The experience on the boats has never changed,” he said. “You can still have the same ride people experienced 80 years ago.”

Hackethorn, who has been with the boat company since 2003 and has a master’s degree in history, started the research to get the boats on the historic register in 2012. He began by writing an amendment to Glacier National Park’s historic building listing, a National Park Service document that records the history of most of its buildings. While Glacier’s boathouses were on the list of historic structures, the boats they housed were not. Once that was written, Hackethorn applied to have the boats included on the register. The Little Chief and Sinopah were added in late 2016, and the DeSmet was added the following December.

Burch said the designation helps highlight the importance of the boats within the park’s history, hardwired as they are into its most prominent bodies of water.

“The lifetime of these boats is infinite, but it requires doing things the old-fashioned way,” Burch said. “The National Park Service is ultimately in charge of determining whether the Burches keep doing this. Given the chance, we’ll keep doing it forever.”