Federal Board to Vote on Changing Offensive Names of Flathead Landmarks

A Blackfeet tribal leader was named to the advisory committee tasked with recommending changes to hundreds of names on federal land across the U.S.

By Micah Drew

As the Department of the Interior prepares to officially rename more than 660 geographic features containing racial slurs across the U.S., including two in Flathead County, it recently appointed a Blackfeet tribal leader to the committee tasked with reviewing and recommending the changes.

On Aug. 9, Interior Secretary Deb Haaland, who has continued to push for the redesignation of landmarks bearing derogatory names on federal parcels, announced the creation of the Advisory Committee on Reconciliation in Place Names, a group assigned to “broadly solicit, review and recommend changes to derogatory geographic and federal land unit names.”

“Our nation’s lands and waters should be places to celebrate the outdoors and our shared cultural heritage — not to perpetuate the legacies of oppression,” Haaland stated in a press release. “The [committee] will accelerate an important process to reconcile derogatory place names.”

The 17-member committee includes Lauren Monroe Jr., vice-chair of the Blackfeet Tribal Business Council, and the only Montana tribal representative on the committee. Monroe said he applied to be on the committee because it aligned with his ongoing advocacy for greater acknowledgment of Blackfeet history in Glacier National Park and the surrounding region.

“The Blackfeet have a longstanding history, some of it really troubled, with reconciliation with Glacier National Park,” Monroe said. “We’ve worked through hard feelings about the replacement of our own history within the park.”

Back in 1915, just five years after the designation of Glacier National Park, Blackfeet leaders met with appointed National Park Service director Stephen Mather in Washington D.C. to protest the use of English-language names in the Park, calling settler names “foolish names of no meaning whatever,” to no avail.

Monroe said that while Glacier’s place names might not be derogatory on their face, many were named by colonial settlers and amount to erasure of Blackfeet culture and history. The awareness of Indigenous erasure in place names has gained traction in recent years, leading to Haaland’s focus on the issue.

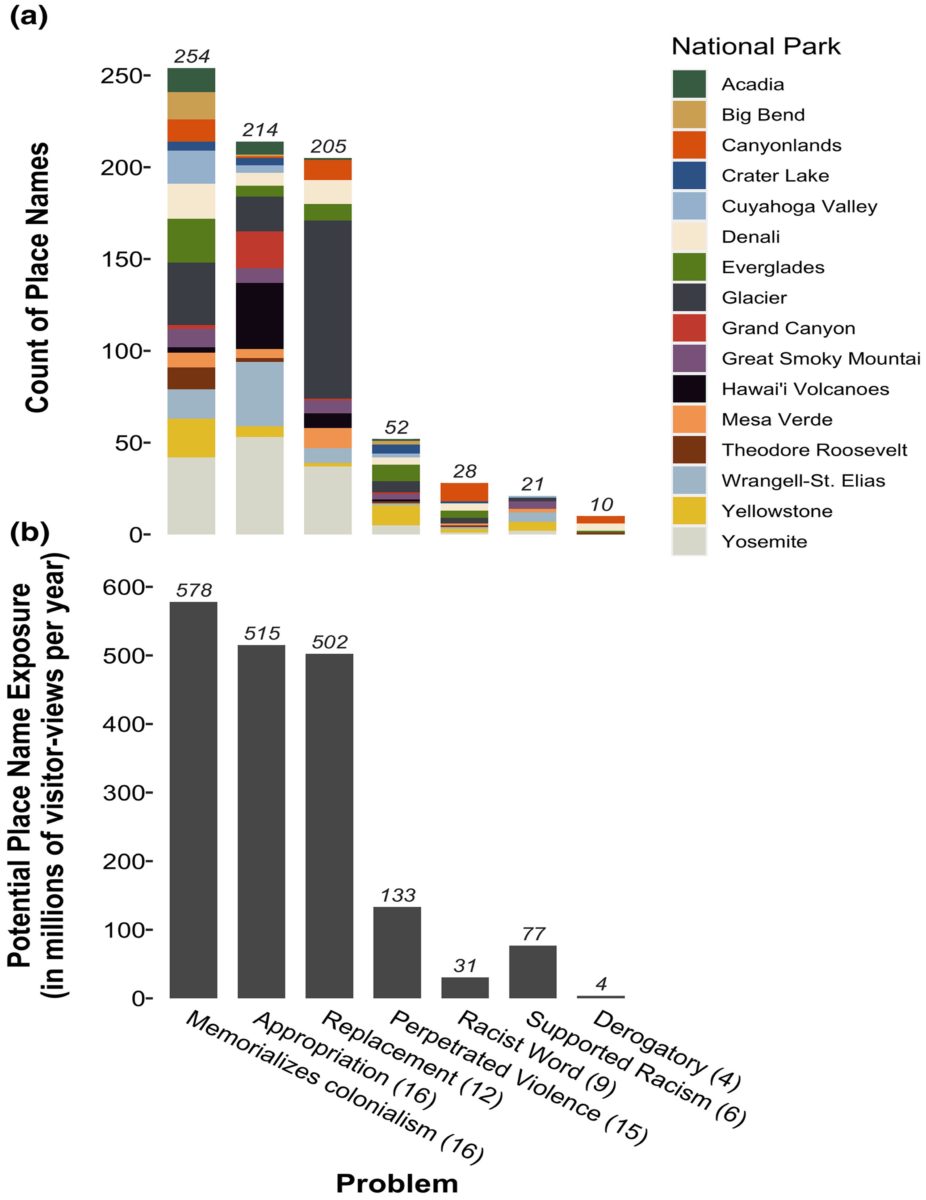

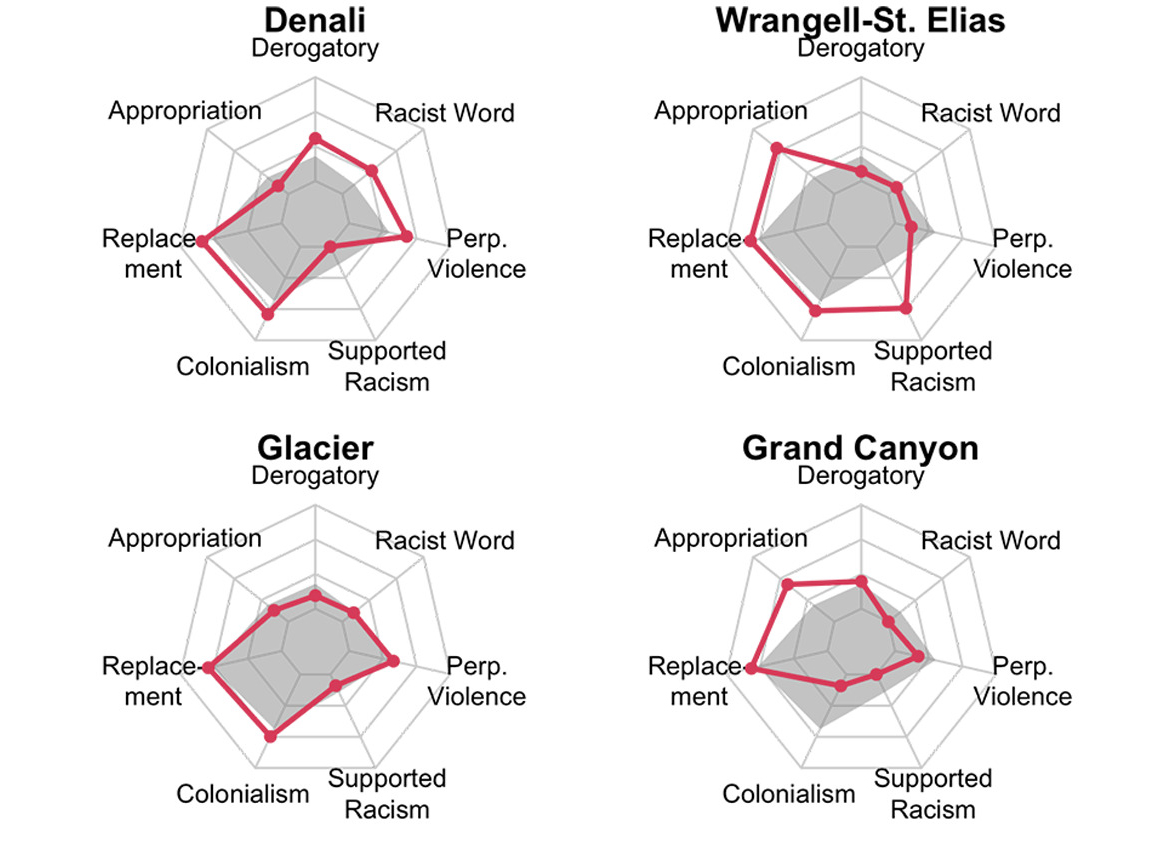

A study by Bonnie McGill and co-authors, recently published in People and Nature, examined place names in 16 national parks and determined whether they were Indigenous names, derogatory, a form of erasure or if they honored individuals who perpetrated violence or racist ideology.

Of the 259 names analyzed in Glacier National Park, 191 were found to be Western-colonial in nature. Ninety-seven of those names are classified as “erasure,” or cases in which the original Indigenous place names are known but have been displaced. Another 68 were classified as “potentially erasure,” where researchers found possible or conflicting original Indigenous names.

The study noted a theme of descriptive names that seem neutral, but still amount to erasure of Indigenous history, such as “Clear Creek.”

“Such names do not record cultural knowledge of place, such as how a place was traditionally used, how the place relates to other features in the landscape, nor help people in the present understand teachings from the past,” McGill wrote.

The McGill study cites several familiar examples in Glacier Park to demonstrate erasure through name replacement, including Elizabeth Lake, which was named for the daughter of a U.S. government surveyor of the park. The known Blackfeet name for the lake is Amu’unis O’muksikimi (Otter Lake), which acknowledges the presence of otters in those waters who “are part of Blackfeet origin stories and whose skin is sometimes used in prayer bundles.”

“The replacement of Indigenous place names erases Indigenous knowledges, a form of ‘cultural genocide,’ and perpetuates the uninhabited wilderness myth by insinuating settler colonizers assigned names to a blank map,” McGill wrote.

Another Glacier name, Chief Mountain, is held up by McGill as an example of how “cultural identity as well as dispossession can be wrapped into the collective memory of a place … and keeps this complex history more in the open than if it was replaced.”

Marias Pass, on the south end of the Park, is another example of replacement. The pass was named for the cousin of Meriweather Lewis following its “discovery” by an engineer for the Great Northern Railway. According to Monroe, it was formerly known as Running Eagle Trail after a fabled Blackfeet warrior.

“It was one of her favorite trails as she went across the pass to prove herself in battle,” Monroe, the Blackfeet tribal leader, said. “She has a celebrated story in our people’s history — that has more significance and history than ‘Marias Pass.’”

Since that initial 1915 meeting, Monroe said tribal elders have periodically raised the issue with park officials with mixed reception. There have even been proven efforts to rename park features, such as Running Eagle Falls in Two Medicine, which was known as Trick Falls until 1977.

More recently, the BGN approved a prominent name change in Yellowstone National Park. Mount Doane was named for a man who led an attack on a band of Piegan Blackfeet known as the Marias Massacre. The peak is now known as First Peoples Mountain.

“We’ve seen that it can be done,” Monroe said. “There is a more significant history about many of these places in our native tradition. It’s not about being politically correct, it’s about being correct. It’s acknowledging the stories of what happened.”

In November, Secretary Haaland issued a pair of orders declaring the term “squaw” a derogatory term and adding it to the list of racially charged pejoratives that have been comprehensively replaced over the years by the Board on Geographic Names (BGN), the federal entity that bears responsibility for decreeing official place names.

Under Secretarial Order 3404, the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) developed a list of locations and offered a list of replacement names to the newly created Derogatory Geographic Names Task Force comprising representatives of various Interior agencies.

“I am grateful to the Derogatory Geographic Names Task Force for their work to ensure that racist names like sq*** no longer have a place on our federal lands. I look forward to the results of the BGN vote, and to implement changes as soon as is reasonable,” Haaland stated in a press release.

In 1999, Montana became the second state to enact legislation to remove the offensive word from state landmarks, but 23 years later a pair of Flathead County locations still carry the slur on maps.

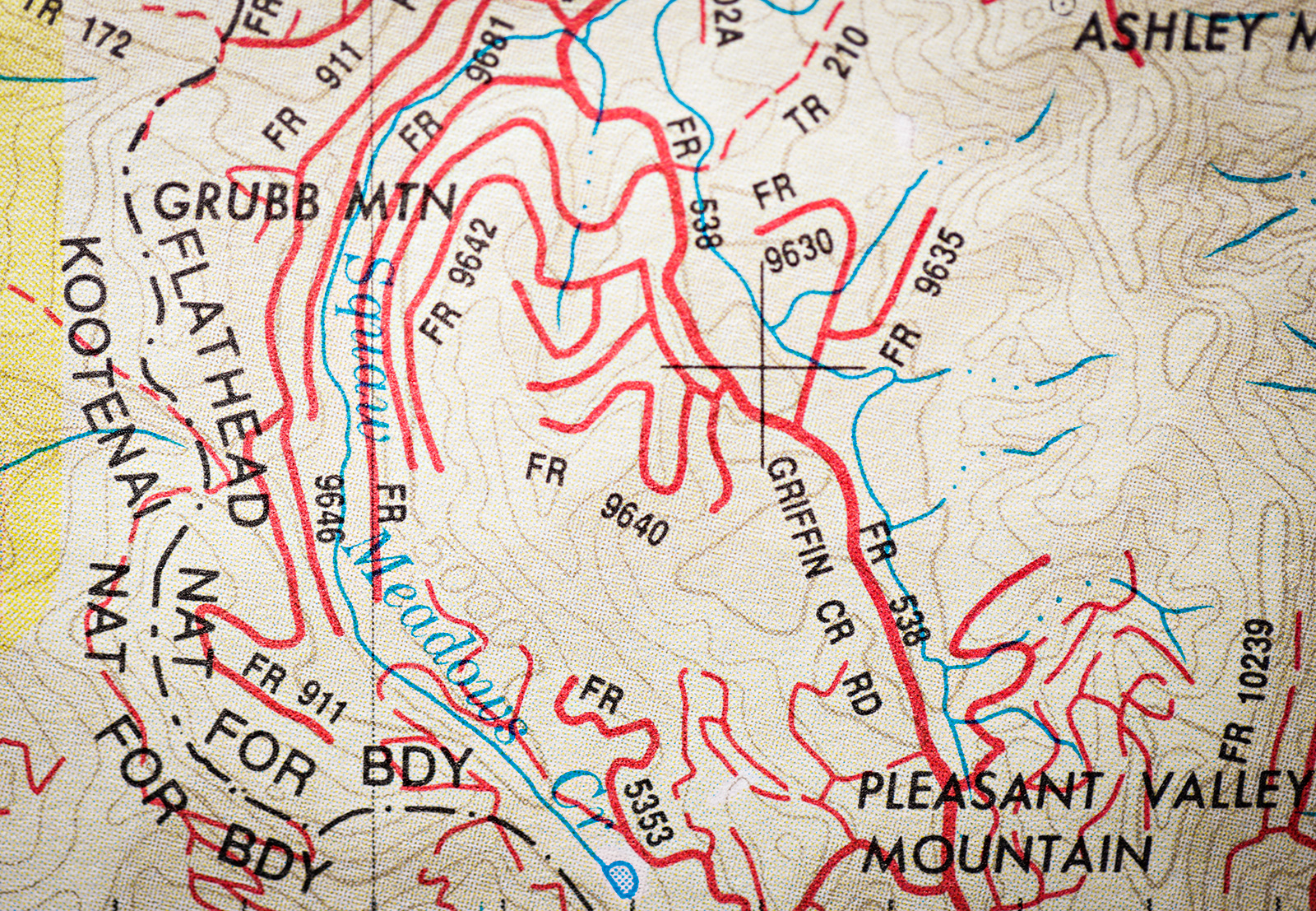

Both Squaw Meadows and the adjacent Squaw Meadows Creek lie just west of Griffin Creek Road north of Marion in the Flathead National Forest. The names were officially published in 1981 and remained unchanged despite the statewide push to eradicate the term.

Gerry Daumiller, a retired GIS specialist with the state of Montana, served as the geographic names advisor with the Montana State Library from 2009 until 2016, serving as the go-between for the state and the BGN when name changes were proposed. Daumiller was involved with proposals to rename Squaw Meadows and Squaw Meadows Creek, but said that between a communication breakdown, his retirement and the lengthy bureaucratic process the proposals must undergo, the changes never made it to BGN.

In December 2021, Daumiller submitted proposals to rename the two features as “Lefthand Creek” and “Lefthand Meadow,” following recommendations by Daniel Stiffarm, the former director of the Kootenai Culture Committee (KCC). The names honor siblings Basil, Mary and Alex Lefthand who were known for their cultural knowledge of the Little Bitterroot region. Stiffarm wrote that the names would recognize “efforts to continue teaching Kootenai Culture, language preservation, Treaty Rights and Tribal Government.”

The current KCC chairman, Vernon Finley, approved of the proposals and the names are currently listed under the BGN’s candidate names list, along with five separate proposed names for each feature.

“I don’t really understand why the process takes as long as it does,” Finley said.

On July 22, the task force announced it had finished reviewing public comment on the more than 660 geographic features and provided replacement name recommendations to the BGN. The BGN is expected to vote on the recommendations at its September meeting.

The Advisory Committee on Reconciliation in Place Names meanwhile, is set to begin meeting in the next few months to begin identifying names of interest.

With 17 members on the committee, tens of thousands of geographic features and many individual priorities, Monroe acknowledges the process of reviewing place names across the country will take time but says it’s a necessary starting point.

“As long as the push is there and we have Interior’s support, I think there can be some headway,” he said. “As a broader discussion of language revitalization and history lessons happening among many tribes, this is under that umbrella of reclaiming history and acknowledging the people who came before us.”