Editor’s note: To mark the 40th anniversary of the Endangered Species Act, the Beacon is featuring two pieces that look at the history of the landmark legislation. Here is the companion feature.

By the spring of 1973, the American conservation movement had reached a boiling point. The early warnings from visionaries like Theodore Roosevelt, who promoted stewardship of the country’s natural wonders and resources or risk losing a sacred heritage, had presaged the concerned state of the wild interior.

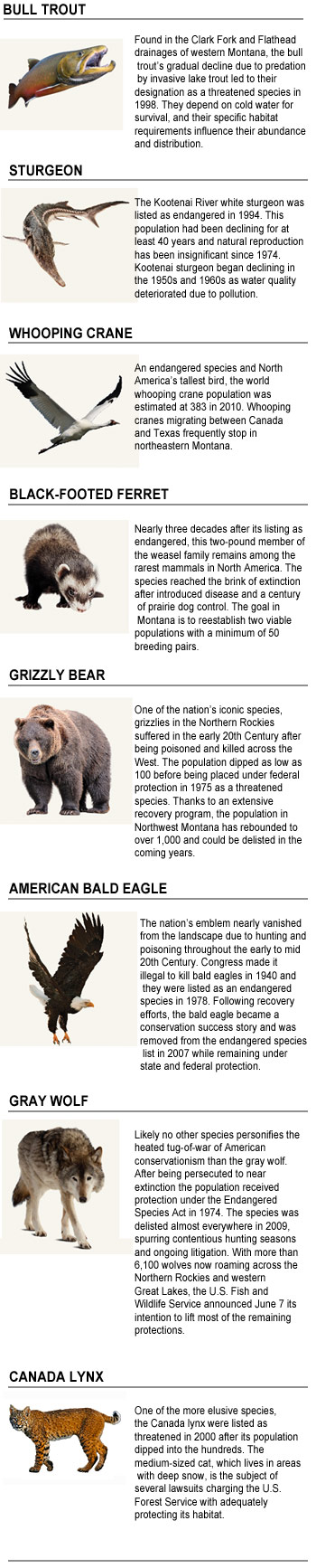

Many of the nation’s iconic species were disappearing from the landscape. The population of grizzly bears had dwindled to only a couple hundred, many of which clung to refuge in national parks, like Glacier. Wolves, once found across most of North America, were reduced to a small pocket in northern Minnesota. Other once common animals — Florida panthers, black-footed ferrets, California condors — were going the way of the dodo. Even the national bird, the bald eagle, was at the brink of extinction.

Indeed, Roosevelt and others opened America’s eyes to the value of wildlife and helped shift public awareness toward conservation. But it wasn’t until a widespread shift in attitude in the 1960s and 70s that actions were finally taken.

|

On June 12, 1973, U.S. Sen. Harrison Williams Jr., of New Jersey introduced the Endangered Species Conservation Act. Similar legislation was introduced in Congress, and both bills advanced exceptionally fast with little-to-no debate. Public support appeared enthusiastic and universal. Not a single special interest group lobbied in opposition. In a move that would make headlines today, all but four members of the House voted in favor of the ESA.

On Dec. 28, 1973, President Richard Nixon signed the ESA into law.

“This legislation provides the federal government with the needed authority to protect an irreplaceable part of our national heritage — threatened wildlife,” Nixon said during the ceremony.

“Nothing is more priceless and more worthy of preservation than the rich array of animal life with which our country has been blessed,” he added.

Since its passage, the ESA has wielded perhaps the most power and influence of any American environmental law. It has also been a perennial source of conflict and controversy, hammered from all sides while trying to prevent the extinction of imperiled fish, wildlife and plants.

Montana, home to many of those species, has had a noticeable presence in the backdrop of the ESA. The early conservation movement can even draw many of its roots to this state. George Bird Grinnell, who helped establish Glacier National Park, became a champion of protecting wildlife after visiting the state and witnessing the decimation of the native bison herd. Grinnell’s close friend, Teddy Roosevelt, frequently used Montana as an example of the richness of America’s outdoor heritage.

“In a place like Montana, conservation is something that is embraced by almost everybody,” said Dan Pletscher, the longtime director of the University of Montana’s revered wildlife biology program, who recently retired after 29 years at UM.

“Preservation isn’t, but conservation is pretty hard to argue against in a place like Montana because that’s why a lot of us are here; the loggers, the miners, the ranchers, the farmers and folks who love to recreate. I can’t think of anybody in the state of Montana who doesn’t benefit by having wonderful wildlife populations and wild areas.”

Today this state remains at the forefront of conservation management practices. State, federal and tribal wildlife officials have taken the lead on many strategies, including the development of a new grizzly bear post-delisting plan and the evolving wolf hunt. In many ways, Montana has become a standard setter for other states that are wrangling with the ESA and the perpetual challenges that surround it.

There are currently 1,476 species in the U.S. protected as endangered or threatened. With a massive backlog of candidate species, the Department of Interior in March vowed to decide the fates of hundreds more by September, which would be the most activity related to the ESA in two decades.

However, while providing protective custody for animals at risk, the ESA has also spurred constant litigation. In just the past four years, nearly 600 lawsuits related to the ESA have been filed, according to the Department of Justice.

The ESA has also been a constant target for overhaul. Opponents of the act describe it as too rigid and lined with red tape. Those in favor of the ESA’s power are wary to let go and quick to question removing protections.

The latest example of the ongoing feud emerged last week, when federal wildlife officials declared their intention to remove the remaining protections for gray wolf, claiming the species is no longer endangered after four decades of contentious and costly recovery efforts.

Instead of receiving praise as a conservation success story, the announcement stirred up sharp criticism, charges of manipulated policy and vowed court battles. Others have accused the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service of doing too much to proliferate the nation’s wolf population.

The outcry and criticism will undoubtedly continue throughout this year’s 40th anniversary.

“There are a lot of critics on both sides,” Pletscher said. “I think there are things that could make the ESA better for most people and species. But for the most part, I think it’s been pretty darn important.”