On Aug. 31, a Great Falls-based company called Montana Land Project, LLC, sent out 1,000 certified letters to property owners in Flathead County. The letters explained that the recipient had two weeks to pay their back taxes, or this company would pay them instead, which, the letter told the property owner in all-capital letters, “COULD RESULT IN THE LOSS OF YOUR PROPERTY.”

Back in July, two other companies sent out 2,300 similar letters to local property owners who were behind on their taxes.

Flathead County has been authorized to transfer property tax liens to private third-party investors since the practice was legalized in 1987. A recent look at the activity in the county reveals that tax lien purchases have increased this year – especially as far as mass mailings are concerned – and, in turn, the amount of delinquent taxes owed to the county has dropped considerably.

But for property owners, the process can feel intrusive when out-of-county and out-of-state companies purchase the liens on their property.

Montana is one of 28 states that allows the transfer or assignment of delinquent liens to the private sector, according to the National Tax Lien Association. Such business is a complicated process, but one that Flathead County treasurer and public administrator Adele Krantz knows well.

“This has been going on for decades,” Krantz said in an interview last week.

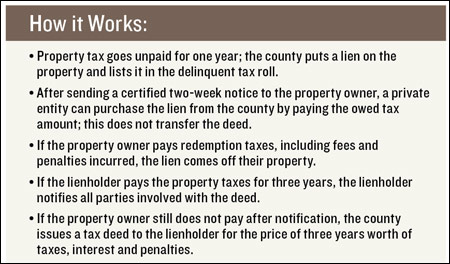

The two-week notices that Montana Land Project sent out in bulk on Aug. 31 are required under state law. Such letters must be mailed when a private entity has intentions of purchasing a lien from a county government. The lien is put in place when a property owner falls behind paying their annual taxes. That property owner has three years to redeem their property before the land is deeded to the lienholder.

Once redeemed, the initial tax amount, along with any penalties and interest accrued, are then paid to the lienholder, Krantz said. Most companies purchase liens for this purpose, Krantz said, because the interest on the initial amount is about 10 percent annually.

“That’s what most people are after, is the interest,” Krantz said.

And before the deed can be transferred, the lienholder has to notify all parties involved with the deed, including banks and relatives, Krantz said, and put a legal notice in the local newspaper.

“It’s a very long process,” Krantz said.

If Montana Land Project successfully buys all 1,000 liens, it would cost the company $1.6 million to pay the total cost of the taxes owed, Krantz said.

In the end, it is possible for a lienholder to get a property deed for pennies on the dollar. That, among other issues, concerned Elaine Thompson, 72, when she received a certified letter from Montana Land Project regarding her son’s property near Marion.

Thompson’s son, Curtis Workman, lives out of state but owns 5 acres adjacent to his mother’s property. He was one year behind on his taxes, Thompson said, and his bill was about $585, including interest accrued.

The property is worth about $10,000 per acre in Thompson’s estimation. If Workman didn’t pay the taxes owed for three years and Montana Land Project did, they get the property deed for the tax amount paid.

Thompson’s family has been on this property and other nearby acres for at least 40 years, and she has fallen behind on her taxes before. But when that happened, Thompson said, she dealt with the county, not with a private entity.

She also found it disconcerting that the company sent out so many letters on Aug. 31, and that many property owners wouldn’t likely get them until after the Labor Day holiday weekend.

“It just upset me so because they sneak it in,” Thompson said.

Thompson paid Workman’s tax bill and they are now square with the county, but the experience made her think about what property ownership means in Montana. Her family may “slip” and get behind once in a while, but that annual tax amount is nothing compared to what they have invested in the property, she said.

“So when do you own your own land? When do you not have to live in fear of losing it?” Thompson said.

The law that allows for tax lien sales in Montana has been in place since 1987, and as far as state Sen. Bruce Tutvedt, R-Kalispell, knows, there are no plans to change it. The process keeps counties funded even if property owners don’t pay their taxes, Tutvedt said.

“It is just a way for the government to get money,” Tutvedt said. “I don’t think there’s anything nefarious with it. Somebody else just picks up the lien and they get the interest.”

The state Legislature has tweaked the law in past sessions, but Tutvedt said that was to ensure the reporting requirements gave property owners adequate notice before anything happened to the deed.

Krantz, the county treasurer, said the county’s concern is that the taxes get paid, not who pays them. And right now, the delinquent tax roll is more than $4 million less than last year.

The total delinquency for personal property and real estate at this time last year was $7,526,442.50. Currently, the delinquency sits at $3,504,202.60. That’s “very, very low” for Flathead County, Krantz said.

|

|

A trailer is seen next to a road cutting through Curtis Workman’s property adjacent to his mother, Elaine Thompson’s, property near Marion. Lido Vizzutti | Flathead Beacon |

Krantz couldn’t say whether the low delinquency total is related to the mass mailings from private companies seeking to buy tax liens, but she said most people make paying their back taxes a priority once they receive that letter.

In July, Krantz reported to the Flathead County Commission that two companies had sent out 2,300 notices to property owners in the Flathead informing them about potential tax lien assignments.

Of the 2,300 notices sent out, the companies only ended up purchasing 377 of the liens, Krantz said.

Lambros Xethalis of LBMT LLC was involved with the July purchase. He is one of at least 36 lien purchasers on record at the county treasurer’s office, and has been working in this business for 15 or 16 years.

Xethalis’ business is based in Hollywood, Fla., but he said he visits Montana “all the time.” The interest rate and penalties for back taxes is the same across the state, but Xethalis said he chooses to buy liens in Flathead County because it is “gorgeous” and one of the most populated counties in the state.

More people typically mean more delinquent properties to choose from, he said. Xethalis also said that Flathead County has a well-run government, making it an attractive investment area.

“I think you guys are fairly technologically advanced,” Xethalis said. “It’s a fairly efficient county, so it makes it a little easier to invest there.”

Investors target other highly populated counties in Montana, Xethalis said, such as Yellowstone County. Max Lenington, the Yellowstone County treasurer, assessor and superintendent of schools, said the business of purchasing tax liens is growing there as well.

“It’s been getting bigger and bigger every year,” Lenington said. “It’s the rate of interest that makes it attractive. For the period of time that the tax lien exists, the assignor gets 10 percent interest (annually).”

This year’s tax lien sales in Yellowstone County are about on par with last year; so far there have been 536 compared to 2011’s 600. But there could be more activity yet, because investors could still be considering the listings on the delinquency roll.

“We could still get a big purchase before the end of the summer,” he said.