A new law passed by the 2013 Legislature broadens the requirements for involuntary commitments in Montana, giving law enforcement and mental health professionals more room to potentially help those in need.

Involuntary commitment means that a person can be placed under psychiatric care for at least a day to be evaluated.

The law, which started as Missoula Democratic Rep. Ellie Boldman Hill’s House Bill 16, changes the language in Montana’s existing emergency commitment law, which originally read that involuntary commitment could happen in “a situation in which any person is in imminent danger of death or bodily harm from the activity of a person who appears to be suffering from a mental disorder.”

Now, the language includes “a situation in which any person who appears to be suffering from a mental disorder and appears to require commitment is substantially unable to provide for the person’s own basic needs of food, clothing, shelter, health, or safety.”

The idea behind the adjustment is that it would give law enforcement and psychiatric officials more leeway to intervene with these individuals before a situation becomes violent or deadly, according to testimony from those who supported the bill.

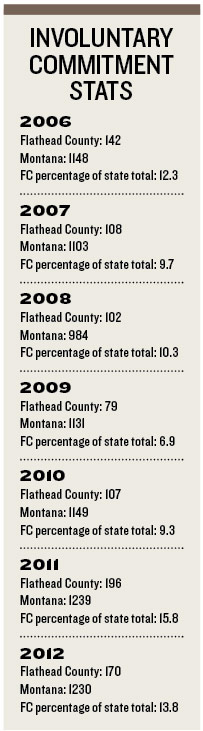

The Flathead already has one of the highest rates of involuntary commitment in the state. According to district court statistics, there were 170 such cases in the Flathead in 2012, equaling nearly 14 percent of the state’s total of 1,230.

That number hit nearly 16 percent in 2011, with 196 cases out of the state’s 1,239 total.

Local law enforcement was not surprised by the Flathead’s standing, which is typically second in emergency commitments in the past several years only to the district court in Missoula.

Sheriff Chuck Curry said he thought the Flathead’s ranking made sense, but not necessarily because there are more people in dire mental straits up here.

“We’re fairly lucky in this county because we have Pathways,” Curry said. “We actually have a place to take people.”

Pathways Treatment Center, which is part of Kalispell Regional Medical Center, provides acute treatment for people who have mental health and/or addiction issues. Such facilities are not prevalent throughout the state, Curry noted, and his colleagues in eastern Montana might face a several-hour drive to take someone in crisis to the nearest facility.

|

“In eastern Montana, they might have to go to Warm Springs, and that might be a six-hour trip,” Curry said. “It’s a huge financial burden for law enforcement in eastern Montana.”

Another reason for higher commitment numbers is the solid relationship between law enforcement in Flathead County and mental health professionals. Curry cited this relationship, as did Kalispell Police Chief Roger Nasset.

Nasset said his officers have workshops with mental health professionals to prepare for situations such as knowing when to take someone to the emergency room to get a psychiatric evaluation.

The new law will give his officers more room to intervene, Nasset said.

“There are so many times where our officers felt that they were obligated to do something but a law wouldn’t allow them to do it,” Nasset said.

Dr. Michael Newman, the medical director at Pathways, said “imminent danger” can be tricky to determine, because there is no definition for “imminent.” Adding the new language to the law can help with that, he said, but it’s still a murky area.

“I think it’s a terrific thing, but you’re balancing the desire to help people with their inherent rights,” Newman said.

It’s not against the law to have a mental disorder, Newman stressed, and that is why it is important to have certain checks and balances in place – such as second opinions and court hearings – when it comes to involuntary commitment.

But some situations are clearer than others, Newman said.

“They have to have the major psychiatric illness. There has to be evidence to suggest they’re not caring for themselves,” he said. “That’s going to be a judgment call.”

While the new law will provide another tool for law enforcement and mental health professionals to help those who may need it, neither Curry nor Newman believed it would dramatically increase the number of involuntary commitments in the Flathead.

“I don’t see it significantly changing the way we do things,” Curry said. “It’s just one more way to intervene and do something positive for somebody.”