On the morning of May 19, Mason Robison and Marc Venery awoke to a bright, brisk spring day in Yosemite National Park. The Montana climbers were in their element, suspended 2,300 feet above the valley floor – more than twice the height of the Chrysler Building – on a pair of collapsible, cot-like porta-ledges they’d anchored to the southwest face of El Capitan the previous night, their fifth spent perched on the vertical wall.

Sorting through an extensive quiver of gear, the climbers were situated just hours from the rim of El Capitan, a colossal monolith of pale granite that has become the touchstone for big-wall climbing. They brewed coffee and noshed a light breakfast while preparing to tackle the 27th of 33 total pitches, each ranging between 100-200 vertical feet. They were confident that by nightfall they would ring in a successful finale to the six-day excursion.

Robison, 38, grew up climbing and mountaineering in the Flathead and Tobacco valleys, earning his chops as a teenager at Stone Hill, a climbing area above Lake Koocanusa, before promptly graduating to ice and aid climbing, a gear-intensive style that requires the use of artificial features, like stirrups, to ascend steep, overhanging rock faces. Through the years he’d made annual trips to “El Cap,” and his travels had recently taken him to Argentina’s Mount Aconcagua, a 22,800-foot behemoth that he solo-climbed in some 13 hours. His YouTube channel, Clmbr4Lyfe, features 132 videos of climbs and adventures all over the world.

“He lived more in one day than most people live in a lifetime,” Michael Robison, Mason’s younger brother, said. “The adventures he had are out of this world. He dreamed big, and he was definitely an El Cap junky.”

Arriving at the base of El Capitan equipped with a deep knowledge of the rarefied sport, Robison planned to spend a month climbing its many routes. He was at the height of his fitness and as ambitious as ever.

“I would say he was probably in his prime,” Venery, who planned to stay in Yosemite about 10 days, said. “We hadn’t even finished the climb and he would already be talking about the next route he wanted to try.”

The two men had climbed together in Montana 17 years earlier, when Venery, a decade older than Robison, took him on some of his earliest ice-climbs. Even though El Capitan was their first trip together in years, the climbing bond was resonant and they set out for California just as the big-wall season began in earnest.

At more than 3,000 feet, El Capitan is revered as some of the best climbing on the planet, and Robison, a native of Columbia Falls, was well acquainted with its most ambitious routes. In October 2011, he solo climbed The Nose via the triple-direct route, scaling an overhanging vertical headwall that consists of more than 30 pitches. Once thought to be impossible to climb, The Nose is regarded by aficionados as a crowning achievement to any climbing career, and by some as the best climb in the world.

“It is very long and extremely difficult to solo and few attempt to do so,” Tom Evans, a photographer who for 18 years has documented climbers ascending El Capitan for his daily blog, www.elcapreport.com, said in an email.

The route that Robison and Venery were ascending is called the Muir Route. It’s slightly longer than The Nose, but more moderate, tracking up the southwest face of El Capitan. Although it is generally considered one of the longest and finest climbs on the face of El Capitan, Muir was not their first choice.

They had intended to climb a route called Horse Chute, also on the southwest face, but as they were preparing gear for the first pitch a park ranger explained that the chute was closed due to nesting falcons. With their plan stymied, they camped just outside the park, re-evaluated their trip and, the next morning, struck out for the Muir.

The route was well within their skill and comfort levels, and they moved quickly but deliberately.

“We were pacing ourselves. We weren’t in a hurry,” Venery said. “We were focused on safety and having fun. Speed was not our primary concern, but we were making good time.”

For Robison, making good time came easy. He’d been doing it his whole life, be it as a cross-country athlete at Columbia Falls High School, an endurance runner and peak bagger in his beloved Glacier National Park, as a climber, or as a stonemason, which, by happenstance, was his trade as well as his name and foremost passion.

“He was a genetic freak,” Michael Robison said. “His lung capacity and his endurance were just unbelievable.”

As teenagers, Robison and his older brother, Mark, often pushed each other to audacious new heights, and once summited 13 peaks in Glacier National Park in 25 hours.

Their fraternal climbing bond came to an abrupt and tragic end on July 3, 1998, when Mark died while attempting to summit Rainbow Peak in Glacier National Park. Mason had intended to join his brother on the trip, but declined at the last minute due to competing obligations and a dearth of space on the requisite ferry to the climb’s approach. Also killed in that accident was Chris Foster, of Whitefish. The climbers were several hundred feet from the summit on a snow-covered chimney when a cornice collapsed and they fell to their death.

That same year, Mason Robison married Lynn, his wife of 16 years. The couple lived in a cabin in Eureka, home to some of Robison’s favorite rock and ice climbing spots, and performed music together around the valley – he on guitar and banjo, she on guitar and vocals.

“He really helped me come out of my shell as a musician,” she said. “His energy was contagious. That’s what I loved about him and that’s why he was so inspirational to people.”

Peter Redmon, one of Robison’s most consistent climbing partners of the past five years, worked with Robison building custom fireplaces and chimneys at Big Prairie, on the North Fork Flathead River. They would live remotely and primitively through the winter, “surviving in the nether-realms of Polebridge,” Redmon said.

Robison was passionate about his craft and his business, Mason Built, which he considered an art as well as a form of cross training for climbing trips. The freedom of his work also allowed him to make long sojourns to distant climbing meccas, like El Capitan, and others in South America and the Himalayas. Redmon accompanied Robison on numerous trips to El Capitan, and recalls one months-long outing during which they spent just seven days on the ground.

“The whole point was big-wall climbing, enjoying life and chilling on a vertical rock face,” Redmon said.

The joy and exhilaration of big-wall climbing is precisely what drew Robison and Venery to El Capitan just as the conditions were entering their prime. Even though the morning of May 19 was chilly, the sun was up and their spirits were high.

“We were psyched,” Venery said. “The mood was upbeat. The mood was upbeat the entire trip.”

After breaking camp, Robison began leading the 27th pitch. Committed to a pure and ethical climbing style, he was elated that they had climbed the entire route “clean,” meaning they placed only removable protection like camming devices, and hadn’t hammered any pitons into the route, which scars the rock face. Having solved the Muir route’s two cruxes the previous day, the six remaining pitches were straightforward and Robison was confident they would complete the climb’s final 700 feet in that pure fashion.

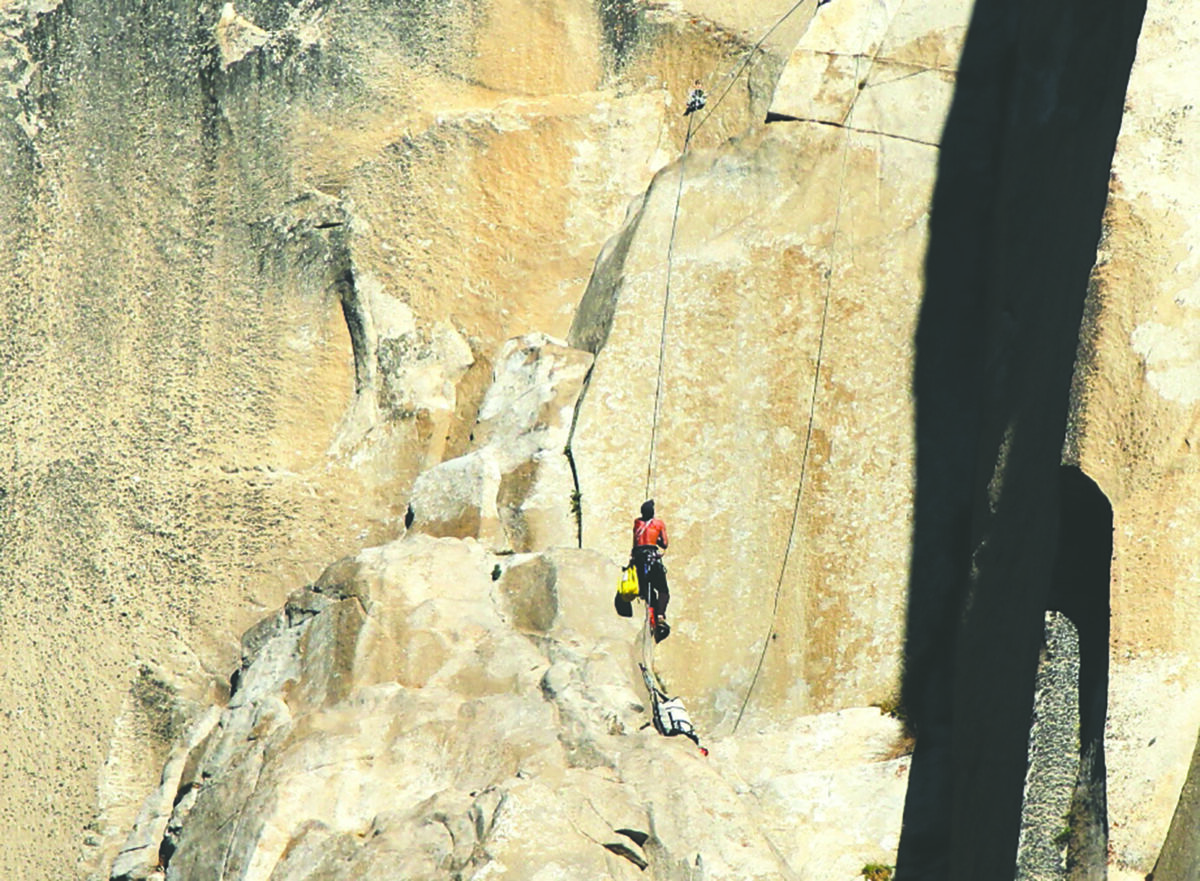

He had climbed about 20 feet above the belay station and was working his way around a large triangular flake. He was placing a camming device above the flake when the giant stone somehow came dislodged and fell atop him. With the rock in his lap, Robison fell outward and past Venery and the belay station. When the lead line came tight to stop the fall, the force of the stone severed the rope, cutting the line about a foot from Robison’s climbing harness.

A haul line, or static rope used to hoist the heavy gear bag between pitches, was fastened to a loop on the back of Robison’s harness, and to an anchor at the belay station. He continued to fall the rope’s entire length, about 230 feet, until the static line came tight. He was killed instantly.

Immediately recognizing the gravity of the situation, Venery tried to make an emergency call on his cell phone, but had no service. Another climbing party below had seen the rock fall and was able to make contact with park rangers. Evans, the photographer and blogger, used his high-powered instruments to view the scene, and told the rangers there had been a fatality.

“In all my 18 years of photographing El Cap I have never seen such a grisly, terrible scene,” he wrote on his blog.

Flying by helicopter, members of Yosemite Search and Rescue, or YOSAR, worked quickly to recover Robison and rescue Venery, who said he was horrified at the prospect that the falling rock had injured other climbers below. Within eight hours he was off the mountain and standing at its base in El Cap Meadow, greeted by heartsick fellow climbers and trying to grasp what had happened.

“It was surreal. It’s still surreal,” he said.

After debriefing park officials, Venery separated his gear from Robison’s so it could be returned to the family. He took care to retrieve his partner’s phone and camera, which contained daily videos of the trip. One after another, climbers approached him, some of them in tears, and offered heartfelt condolences.

“The outpouring of sympathy from other climbers was amazing. It blew me away,” he said.

When he arrived back at his truck, it was covered in notes and memorials, the climbers having recognized his Montana license plates.

“That was unbelievably powerful,” he said. “The positive energy and the vibe at El Cap is amazing. It’s a whole other dimension. Mentally everyone is so tuned in. Mason was really in his environment there. He loved it. He was energized by it.”

After making the two-day drive back to Montana, Venery met with Robison’s family and told them the whole, emotional story, a courtesy that was not afforded to them when their eldest son died, because his lone climbing companion had been killed, too.

“When Mark died, Mason thought the best way to honor him was to keep climbing and pursuing his passions,” Michael Robison said. “I think that’s what Mason would want from others.”