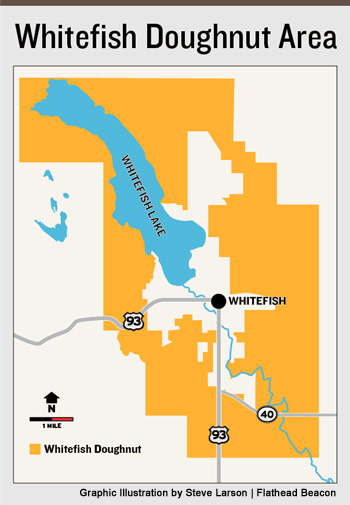

WHITEFISH – A decisive court ruling returned authority of the embattled Whitefish planning “doughnut” to Flathead County, but a new growth policy redefining the course of future development in the two-mile belt girding the city’s outer edge could be hamstrung as an appeals process gets underway.

Many key players familiar with the long, litigious turf war over the amorphous planning doughnut were nonplussed by Flathead County District Judge David Ortley’s July 8 decision – not because the order was unclear, but because the next legal steps cast a pall of uncertainty over long- and short-term land-use planning adjacent to Whitefish city limits, where zoning authority has been volleyed back and forth for years.

“It is very likely that we are going to appeal. There is enough support. But what happens in the meantime is all up in the air,” Whitefish City Councilor Bill Kahle, who was instrumental in early land-use negotiations with Flathead County Commissioners, said.

The contentious doughnut issue has been plodding along for a dozen years, and the most recent lawsuit, filed less than two years ago by four Whitefish-area residents, challenged the validity of a citizen-initiated referendum passed by Whitefish voters in November 2011. That referendum, which Ortley’s recent ruling declared illegal, struck down a 2010 planning agreement designed as a compromise between city and county officials and, in doing so, shifted full jurisdictional authority of the doughnut area back to Whitefish.

The move was seen as a triumph by some doughnut residents but rankled others and, following passage of the referendum, area residents Lyle Phillips, Anne Dee Reno, Ben Whitten and former Whitefish Councilor Turner Askew filed a lawsuit asking Ortley to declare it illegal and void. They argued the county should maintain authority because the 2010 agreement was an administrative, rather than legislative, act, and was therefore not subject to referendum.

In his July 8 order, Ortley sided with the plaintiffs, granting summary judgment and declaring the referendum invalid. The order also lifted an injunction that had prevented the county from applying zoning regulations to the doughnut area while the case was in litigation.

“The county may proceed with the establishment of zoning regulations applicable to the former doughnut area as provided by law,” Ortley wrote.

Following the order, Whitefish city officials filed a motion for a stay that would restore the injunction pending an appeal to the Montana Supreme Court.

Kalispell attorney Duncan Scott, who represents the four plaintiffs, then filed a motion opposing the city’s request for a stay, calling the decision to file the motion illegal because it was made “behind closed doors and without notice.”

Kahle expressed frustration with the interminable litigation, which he said is creating an impasse and has further entrenched various sides previously on the brink of compromise. Instead of an olive branch, he said, there has been a flurry of frustrating legal constraints.

“When I got elected my goal was to move this issue out of a courtroom and around a negotiating table, and we did that for a year,” he said.

The result of those negotiations, Kahle said, was a plan that laid out a multi-step solution, creating a system whereby any new legislation introduced by city council was subject to review by county commissioners; if they did not approve, the issue would be taken up at a negotiating table. The plan also stipulated that the county could withdraw from the agreement if it gave a full year’s notice.

“It was my feeling that unless we went off the deep end with some outlandish proposals we were going to be OK,” he said. “I thought that as long as we played nice in the sandbox there would be no reason for the county to initiate the one-year termination.”

Kahle called the citizens’ referendum, which he strongly opposed, “a slap in the face to the county,” and blamed its passage for prompting further litigation and engendering ill will.

|

“We spent a year in negotiations and then this [referendum] happens,” he said. “We have allowed a judicial element into what I think should be a community land-planning conversation. It turned the issue into a zero-sum game in which we either stood to win everything or lose everything. And guess what? We lost.”

In a statement, Scott said the court ruling “is a welcome victory for the 5,000 doughnut property owners who have suffered for more than five years under Whitefish’s ‘regulation without representation’ form of government.”

He continued: “In addition to the referendum being illegal, as Judge Ortley has ruled, it was an insult to doughnut residents, who were the affected parties but could not vote on it. Whitefish cannot win this fight. If the Montana Supreme Court reverses Judge Ortley, which we think is highly unlikely, and somehow the old 2005 interlocal agreement springs back to life, then the county itself can put a referendum on the ballot to repeal the 2005 interlocal agreement. In a countywide election, where doughnut residents can actually vote, does anyone seriously think Whitefish would prevail?”

The original 2005 interlocal agreement gave Whitefish zoning and planning control of the doughnut area, but in 2008 the county single-handedly rescinded the agreement because it did not give doughnut residents, who cannot vote in city elections, adequate representation.

A major point of contention arose that same year, when Whitefish adopted a city critical areas ordinance, which called for setbacks from water bodies and set standards about the grade of slope that can be built on. It also imposed regulations about storm water management and other water quality standards. The ordinances include the doughnut area, which upset some residents and business owners who complained that they are beholden to city rules but unable to participate in the public process.

The city responded in January 2012, asking the court to enjoin and include Flathead County in the litigation, while Dan Weinberg, Ed McGrew, Mary Person and Marilyn Nelson joined the litigation as intervenors.

Nelson, a downtown business owner and doughnut resident living on Blanchard Lake, said she was disappointed in the court’s decision because it infringes upon Whitefish voters’ rights to determine the future of the community.

“Their right to exercise an opinion was denied by the court,” she said. “I pay substantial city taxes even though I don’t get to vote, which has never bothered me because I participate in the public process and every time I go to city council my opinions are respectfully heard.”

Nelson said she worried that reverting back to county land-use planning control would compromise the unique character of Whitefish, including ordinances that protect its open spaces and restrict strip development and blight – the sign ordinance and dark skies initiative regulating light pollution, for example.

“It would be different if Whitefish wasn’t such a distinct entity. But numerous ordinances are in place to preserve the unique characteristic of Whitefish,” she said. “Left to the county I think that there would be a very different sort of model for zoning in the perimeter of Whitefish.”

Real estate agent and doughnut resident Tom Thomas formed the People of the Doughnut group, and decried what he characterized as the Whitefish City Council’s carte-blanche planning authority over the doughnut, which he said has had a deleterious effect on development.

“They are so hellbent on doing things their way that if they could they would control all the way to Kalispell,” he said. “We don’t want to be part of a Gestapo-type organization, and that’s what Whitefish is going to do to the doughnut. That’s why we are fighting so hard to stop it.”

Whitefish Mayor John Muhlfeld called for a cooperative resolution through round-table discussions, and said the city’s decision to request a stay is an effort to “maintain the status quo for the doughnut area throughout the appeal,” rather than a legal barb.

|

|

Traffic moves south on U.S. Highway 93 between downtown Whitefish and MT Highway 40. – Lido Vizzutti/Flathead Beacon |

“For more than 45 years, the city and the county have worked together cooperatively in making land use and zoning decisions,” Muhlfeld said in an emailed statement. “I believe the city and the county need to resolve their current differences and find a cooperative way to work together again for the betterment of their mutual residents and tax payers.”

Given the freedom to move forward with its new land-use and zoning policy, the county would cast an air of confusion on doughnut residents uncertain where planning authority lies, he said.

“We are disappointed by the court’s recent order,” Muhlfeld said. “The order allows an abrupt change over to county land-use and zoning authority which will cause unnecessary uncertainty and expense to city and county residents and in particular to the doughnut residents.”

Whitefish City Council held a closed executive session Monday, July 15 – after the Beacon went to print – to officially determine whether or not the city will appeal the decision.

Whitefish Councilor Richard Hildner, a proponent of the referendum, said attorneys on both sides of the matter made it clear during oral arguments in February that an appeal was probable no matter the judge’s decision. Additional legal wrangling is not only likely, he said, but necessary to put a complex issue to rest.

“To me, as lugubrious and laborious as this process has been, it is one that I think all sides respect and that we have to live with,” he said.

Nelson said too many questions are left unanswered, and complained that she has not received a definitive answer about what would become of the neighborhood plan that she and other Blanchard Lake residents drafted.

“I am concerned about protecting my lifestyle. And my lifestyle would be threatened if my property on Blanchard Lake was surrounded by apartment buildings, convenience stores, pig farms or whatever else might be allowed if there is nothing to honor our neighborhood plan,” Nelson said. “I live in Whitefish. I may live in the doughnut but I am part of the Whitefish community. People who live here consider ourselves part of the Whitefish community and handing authority of the doughnut over to the county means giving up our ability to shape our community.”

Scott, attorney for the plaintiffs, encouraged the majority of Whitefish city councilors to reject an appeal.

“Whitefish cannot win this fight,” he said. “After five years of litigation in multiple lawsuits, and dozens of contentious public meetings pitting neighbor against neighbor, it’s time to end the strife. Let the doughnut people be free.”

Tired of characterizing the issue as a “fight,” Kahle advocated mediation between the parties, saying compromise is achievable.

“I would certainly be open to having a cooperative sit-down discussion with the county,” he said. “Everyone has a lot to gain by working this out around a negotiating table.”