In back of the yellow, Blue Bird school bus, members of the Whitefish High School wrestling squad lay sprawled across the vinyl bench seats, their legs slack and spent, dangling in the aisle as they dozed or chatted idly, cobbling together last-minute Saturday night plans.

It was Jan. 21, 1984, and the Bulldogs were returning from an afternoon dual in Browning. Driving through the winter darkness, bus driver Jim Byrd, a well-known Columbia Falls resident with 59 nieces and nephews, negotiated the narrow, snow-choked corridor of U.S. Highway 2, a two-lane, 94-mile stretch of winding road between Browning and Whitefish that tracks along the Middle Fork of the Flathead River, skirts the southern border of Glacier National Park and, at its zenith, tops out on the Continental Divide and Marias Pass, at an elevation of 5,216 feet.

It was around 6:30 p.m. and the bus was 20 miles east of West Glacier, homeward bound.

A blizzard had been steadily spitting flakes throughout the day, covering the valley in a slippery vale of winter white. Before departing from Browning, the team stopped at Teeple’s IGA grocery store for snacks and to discuss the possibility of spending the night or waiting out the storm. Crossing Marias Pass would be dicey, but probably passable, they reasoned; everyone was eager to return home and sleep in their own beds.

“We were nervous about the roads. We knew when we left that it would be tense, but it was a collective choice we made to go home. It was a team decision,” recalls Steve Osborne, a junior at the time. “Being high school kids, you don’t stress about it too much. You just sit back and start yakking.”

Back in Whitefish, the annual Winter Carnival was underway and the festive royal coronation was slated for that evening. The Whitefish High School basketball team was playing a home game against Deer Lodge.

At the front of the bus, members of the cheerleading squad gossiped while two girls hatched tentative plans to see a movie when the team returned to town; “Hot Dog … The Movie,” the iconic ‘80s ski comedy, had just been released.

The upper-classmen had taken over the back of the bus, and Scott Norby, a junior, 165-pound heavyweight seated in one of the last rows, figured he and some friends might hang out downtown that night, maybe go for a drive.

“We were all just doing what kids do. We were in the back and everyone had their own seat. I was taking up a whole bench seat, sitting with my back against the window with my feet hanging out into the aisle,” Norby recalled. “We were telling jokes and screwing around. Everyone was asking each other what they were going to do when they got back to Whitefish. ‘Are you going home or are we going to cruise around?’ It was Saturday night.”

The smallest member of the Whitefish High School wrestling team, freshman Travis Brousseau, who was competing at 98 pounds, was seated up front in the third row, just behind the coaches and the cheerleaders. He and teammate Brent Halverson were listening to the song, “Bang Your Head,” by Quiet Riot, on Brousseau’s Astraltune, the bulky, pre-Walkman portable cassette player.

Up front sat Head Coach Jim Withrow and Assistant Coach Wayde Davis, as well as Davis’ wife, Jana, his 3-year-old son, Casey, and his 5-year-old daughter, Brieanne. The young family frequently accompanied Davis to out-of-town meets, and while Casey sat nestled on his mother’s lap, Brieanne eventually grew restless and scrambled to a seat a few rows back, joining 17-year-old cheerleader Lisa Slaybaugh. Ahead sat Stefanie Daily and Pam Fredenberg, the top candidate for school valedictorian, and a clutch of other young cheerleaders.

The capricious seat change, a youthful whim, would save the young Davis girl’s life.

Early that morning, Withrow had awoken in the basement of the home he and his wife, Emily, were building just outside of Whitefish. They were living in the basement temporarily, until they finished construction, and their son, 14-month-old Ian, was slumbering peacefully in the cramped quarters.

When Coach Withrow peered out the window and saw that it was storming, he shook his head, knowing the roads would be hazardous, particularly along the constrictive stretch of Highway 2 and over Marias Pass, or “the hill.” It was two weeks before the couple’s second wedding anniversary.

“He turned to me and said, ‘we have no business going out there,’ and I said, ‘no, you don’t,’” Emily recalled three decades later.

Jim Withrow moved to Whitefish from Washington in 1979 to teach junior high biology and, a short time later, to coach high school football and wrestling, a program he shaped and defined. Most of the community had no concept of high school wrestling, including Emily, who upon meeting her future husband envisioned a theatrically roped-off ring, a la the gratuitous World Wrestling Federation that was popular at the time.

When Emily first laid eyes on Jim, he was sitting among a group of football coaches at the old Viking Bar. The 1979 Bulldogs had just won the Class A state football championships, which to this day remains the only football championship in school history, and the coaches were celebrating.

“I had just moved from San Diego and was living with my sister. We had gone out dancing and I walked by his table. He was at a table with a bunch of football coaches and I looked at him and thought to myself, he is extremely handsome, which he was, but I bet he’s a jerk,” she said. “Then he asked me to dance and that was pretty much it. He was humble and generous and kind and hilarious. He would do the soft shoe for the kids before they left on the bus. And he had a laugh. You couldn’t help laughing with him.”

Knowing that Coach Davis’ family was joining the wrestling team on the trip to Browning that winter morning, Emily suggested that she and Ian come along, too.

Coach Withrow refused, saying he didn’t want his wife and infant son along for the drive, out on the snowy roads.

Later, Emily would regret the decision, wishing that she’d been sitting beside her husband and the Davis family.

“After the accident I was really mad at him because I would have much preferred to die with them. Those were our best friends,” she said of the Davises. “We did everything together.”

Before departing for Browning, the team milled around outside the high school, waiting for their usual charter bus and then watched in disbelief as the yellow school bus pulled up.

“Normally we were in a diesel charter bus, and here we are about to trek over the hill in this damn school bus,” Norby said. “Coach Withrow wasn’t happy about it, but it was our only option. Later that night, we wondered if anyone might have fared better or worse if we had been on a big diesel charter bus. Those were the conversations we had.”

After the dual against Browning, the captain of the team, senior Dennis Spurlock, who weighed 155 pounds, was relaxed and content after having won a difficult match that afternoon. In particular, his spirits were buoyed by the accolades he’d earned from Coach Withrow.

Spurlock had trained with the burly, six-foot-three, 210-pound, tousle-haired, mustachioed, and extremely popular head coach since he was in eighth grade, having convinced Withrow to let him travel with the varsity wrestling team as manager, which, despite his young age, allowed him to develop his chops on the mat. Unconventionally, he lettered that year, as he did every year of high school.

For Spurlock, whose own father worked long hours as a logger, Withrow was more a father figure than a coach, and frequently dished out advice about girls (“leave them alone,” he’d tell the young wrestler) and offered counsel about college prospects.

Splayed out in the very back of the bus near Steve Osborne, who was also a captain, Spurlock drifted in and out of sleep. He had his sights set on the state championships, which were just three weeks away, and he was gunning for the state crown — a title that had long eluded the fledgling Bulldog wrestling program, except for when the Tarr brothers, Mark and Warren, won years earlier.

Under the auspices of Withrow, most locals recall the 1984 Whitefish wrestling team as the program’s paragon achievement, and Spurlock wanted to capitalize on the squad’s momentum.

“We’d just had the match in Browning and it was a tough match. I had to lose a lot of weight beforehand and it was tough, but I won,” Spurlock recalled. “Afterward, Coach Withrow gave me a big bear hug. He said, ‘you’ll get another hug like that in three weeks at you-know-where.’ He was insinuating about going to state. In my mind, my ultimate goal was to win and get that hug from him. He was a real father figure.”

Spurlock was half-asleep when he was jolted from his reverie, unable to anticipate the unimaginable tragedy that would unfold in a split second, but which for months felt to some like a bad dream, a neverending nightmare.

“I had it in my head for months that eventually I was going to wake up from a dream, that I’d wake up in the back of the bus and we’d be pulling into Whitefish, all of us safe,” Osborne said.

Instead, the fiery collision would go down in the record books as the deadliest in Montana’s history, killing nine people and injuring 18 others on board.

Barreling east on the cold, dark highway, Harold Belcher, 63, of Cutbank, was piloting an empty gasoline tanker with a trailer pup attachment when the rig slid out of control, jack-knifed and began sliding crosswise down the highway.

By the time the broadsided tanker emerged from the darkness and the snow flurries, there was scarcely time for Byrd to react. The truck collided with the bus, its front end bursting into flames.

“What I remember was just a real quick sound of locking-up brakes. I was sitting above the rear wheel well of the bus and I could feel the slamming on of the brakes,” Norby said. “There was no swerving, there was no riding it out. It was just slam on the brakes and kaboom. It was instantaneous, a split-second deal. I remember the loudest crack you could imagine and then I was airborne. Everybody was airborne.”

The force of the impact sent the wrestlers and cheerleaders flying into and over the seatbacks, which toppled like dominoes as the athletes and the seat rends slid toward the front of the bus in a chaotic heap, knocking some unconscious and breaking others’ bones.

Spurlock remembers that his first conscious moment after the crash was staring through the rear-exit window at Belcher, the truck driver, whose face was streaked in blood as he approached the door with a pry bar to force it open.

“That was the first face I saw, and my first instinct was to get out of this vehicle,” Spurlock said. “I got like 10 steps and realized I had to help everybody get out. The front of the bus was on fire almost on impact. A few of us got people organized. We were carrying those who couldn’t walk. Everyone was in shock.”

“[Belcher’s] head had slammed into the side of the truck,” Norby said. “He met us all bailing out, saying, ‘sorry kids, I tried to put it in the ditch.’ He was bawling. He knew what kind of mess had just transpired and then somebody, the police maybe or the highway patrol, grabbed him and started interviewing him. I never did see him again.”

Even though the front of the bus was engulfed in flames and some students thought it might explode, the wrestlers sprung into action, lifting and carrying anyone who was too injured to walk. With the front of the bus burning, they knew they could only do so much.

“There was a fine line separating those who died and those who lived,” said Norby, who fractured his hip but was too adrenalized to notice the injury as he helped carry cheerleaders out of the door and down the road to Denny’s Inn, a bar, café and motel, a quarter-mile away. “If you were in the third seat on either side of the bus and back, you survived.”

He continued: “Half of the bus was on fire. All the seats and the plastic were burning. We were carrying anyone that couldn’t walk and I remember Dennis was trying to bear the heat and go up front, knowing that there were people inside, that the coaches were up there. It was pretty crazy. We just huddled outside trying to figure out what the hell to do. We thought the bus was going to explode, like in the movies.”

Brousseau’s leg was broken, his tib-fib snapped on impact, and he lay helpless beneath a pile of crumpled bus seats, which Norby helped lift off the freshman so he could crawl out. Meanwhile, Osborne was extracting the surviving cheerleaders from the debris.

“I was sitting right behind the cheerleaders. Everybody in front of me died,” said Brousseau, who along with Halverson managed to hop out of the bus and hobble a quarter-mile down the road to Denny’s Inn, half-jumping and half-leaning on his teammate for support.

“I knew right where we were and that Denny’s was just down the road. That’s where everyone ended up, where we all converged. It was a like a triage area,” he said.

Norby recalls the entire team helping one another down the road and, after about 50 yards, hearing the tires on the bus blow up. When he turned around, the bus was fully engulfed.

“There was nothing anyone could do,” he said.

Inside the bar, one wrestler was stretched out on the bar and Slaybaugh, one of two surviving cheerleaders who’d been knocked unconscious and carried to safety by her boyfriend, sat on the pool table, icing her leg and waiting for emergency personnel to arrive.

Cheerleader Sue Stocking had suffered serious internal injuries, including a pierced lung, and Brousseau recalls holding her hand during the ambulance ride to Kalispell.

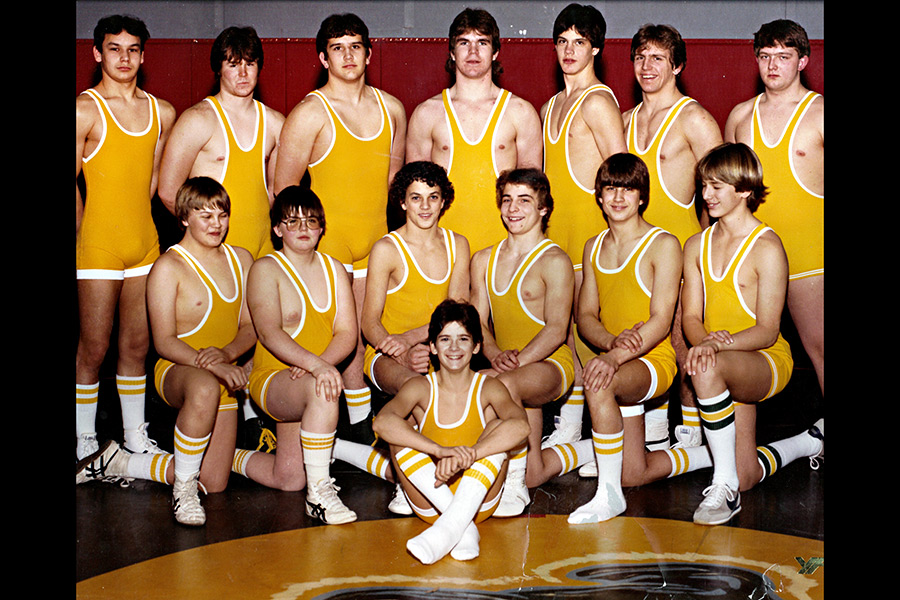

Bottom row, left to right: Chris Mee, Mike Bos, Todd Ricker, Brent Halverson, Larry Hanson

Photo Courtesy of Travis Brousseau

At Denny’s, which still stands but has since been re-named the Glacier Haven Inn, team captains Spurlock and Osborne began taking stock of those present. On a piece of notebook paper, they wrote down who was accounted for and who was missing. After a few minutes, they’d winnowed the list down to nine people, all of them dead.

They were head wrestling coach Jim Withrow, 33; bus driver Jim Byrd, 41; assistant coach Wayde Davis, 27; his 24-year-old wife, Jana, and 3-year-old son Casey; team statistician Pamela Fredenberg, 16; and cheerleaders Kim Dowaliby, Tracy Maddux and Stefanie Daily, all 16.

Brieanne, the young daughter of Coach Davis, approached Spurlock and asked where her parents were; the team captain had no words.

“I just said, ‘they’re not here, honey,’” Spurlock said. “She knew they were gone, but what do you say? That really broke me up. She was so small. She had glass and cuts on her face.”

The captains also monopolized the bar’s pay phone and instructed everyone to call their parents, allowing each student two minutes to explain what had happened and assure their loved ones that they were alive.

Brousseau recalls that his parents didn’t know whether he was alive or dead, and later found out that they’d assumed the worst.

“It took me years to get over this thing. I still have nightmares about it,” he said.

Seated in a booth inside the bar, Norby recalls trying to join Spurlock in returning to the crash site to look for survivors, but when he tried to stand up he couldn’t move, realizing that he’d broken his hip.

“A few minutes earlier I’d been carrying people, and all of a sudden I couldn’t stand up,” he said.

Always the leader, Spurlock remained calm and in charge, calling the school to explain what had happened, though it took several attempts to convince administrators that the calls of distress weren’t a tasteless prank, and that the unthinkable had occurred.

“I was captain of the wrestling team, so it just kind of felt like an obligation to keep everybody calm until help arrived,” he said.

News of the crash spread quickly through the town of Whitefish, which was home to about 3,700 residents at the time, but it would take hours for authorities to confirm the names of the nine victims.

Scot Ferda, who today teaches at Whitefish Middle School, was in the high school gymnasium watching the basketball game when reports of the crash began trickling in. A close friend to many on board the bus, including both coaches, he felt the blood drain from his face.

“There’s a generation of people who remember exactly what they were doing when they heard John F. Kennedy was assassinated. There’s a generation of people who remember precisely where they were when they heard about 9/11. In Whitefish, there’s a generation of people who can remember every detail of the moment they heard about the wrestling team’s bus crash in 1984,” Ferda said recently, just prior to leading a moment of silence at a Bulldog wrestling match against Columbia Falls. Ferda called out the names of those lost in the tragedy 30 years after it occurred, almost to the day.

Emily Withrow remembers in painstaking detail the gut-wrenching moment she heard of the wreck.

“I was rocking Ian when I got the call. All they said was that the wrestling bus has been in an accident with a truck. That’s all they could say,” she said. “I just kind of waited and all of a sudden neighbor ladies started showing up. It became more and more apparent that this was serious. They said, ‘what can I get you?’ and I said, ‘Jim. I want Jim.’ I knew that he would have called if he’d been OK, but it was four hours until I found out he’d died, four hours of wondering, is he or isn’t he? It was horrible. I remember looking out the window and thinking, I really don’t want to do this alone.”

The tiny community immediately banded together in support and to mourn, everyone devastated, remembered former Whitefish Mayor Jim Putnam. In the days that followed, a media circus descended on the remote town. NBC’s Roger O’Neil interviewed students in an empty classroom, recording their tears as they described the final moments before the crash and its aftermath. The New York Times covered the crash and wire stories appeared in nearly every national paper.

Putnam ordered all flags flown at half-mast and a memorial was organized. President Ronald Reagan sent the civic leader a letter expressing his and Nancy’s condolences, a gesture the former mayor remembers well; he can still quote the letter by heart.

“When this happened, since everybody knew everybody in Whitefish, everybody felt that those kids were their own kids,” Putnam, now 85, said, noting that the ski town was on the cusp of a boom that would transform Whitefish. “There was a tremendous divisiveness about the growth occurring, but the new people coming in had as much compassion as anyone and it brought a peace and tranquility that I have never seen before among the people of Whitefish. It settled everybody down and brought people together.”

Emily and Ian Withrow remained in Whitefish for one year. She remembers the outpouring of compassion from the school and the wrestling and football teams, whose members filled the ‘84 school annual with notes to Ian, describing his father as a great and influential man, an inspiring coach who provided direction and support. Still, whenever she walked through town, she was greeted with hugs and tears, a painful reminder of her loss.

“I thought if I was ever going to move on, I would have to leave town,” she said, and settled on Missoula. Before she left for good, the wrestlers and football players helped her load up the moving van.

Most members of the wrestling squad were either too injured or too emotionally wrecked to travel to the state championships in Miles City three weeks later. A talented wrestler, Norby was out for the season and would discover his senior year that memories of the crash were too painful. He never wrestled again.

“It changed everything for us. It really affected me. I couldn’t get back on the mat again,” Norby said. “Those two coaches were really important people to me and I knew that they would have wanted for me to continue on. But I just couldn’t force myself to do it. It was my senior year and everyone said, ‘you have a shot at winning it all.’ I just couldn’t do it.”

After the crash, Spurlock couldn’t walk without support for a week, having injured his shoulder and legs when he smashed through his seatback.

Despite the injuries, he was determined to compete at the state meet.

“I was pretty banged up but I had a lot of motivation, I guess,” he said.

And so Spurlock, along with an interim coach and several other uninjured teammates, including Osborne, flew to Billings and caught a ride, on a bus, with the Laurel wrestling team to Miles City.

“I was a mental wreck. I almost got beat. It was so emotional, but then I turned it around. I just looked at that kid and said, ‘there’s no way you are going to beat me. I’ve been through too much to get here,’” Spurlock said.

Spurlock kept his promise to Withrow and, against all odds, won the state championship, earning his school, his teammates and his coaches a crowning achievement. He also earned Withrow’s hug.

“That’s the way I felt after I won. Even though he wasn’t there, I earned his hug.”

Steve Osborne went on to teach high school algebra in Columbia Falls. Inspired by Withrow, he wanted to make an impression on the lives of young people. Of the 23 years he’s been teaching, he has coached high school wrestling for five of them and middle school wrestling for 17; he recently took a break to allow his son to compete without being labeled “the coach’s son.”

Upon returning to Whitefish after the meet in Miles City, he gave his team championship medal to Emily Withrow.

“A big part of my life’s goal has always been to be a person that Coach Withrow would smile down on and say, ‘wow, he’s on the right track,’” Osborne said. “My motivation was to do something with my life that would make him smile, and a lot of that is due to what we all went through. He just made us better people.”

Osborne recalled riding his bike to Withrow’s home in junior high to catch rides to wrestling meets.

“I didn’t have any family involvement, so he would check my grades and help me set goals,” Osborne said. “He was a person that cared. And he was a pretty light-hearted guy. You could always catch him in the hallway doing his little soft-shoe dance.”

Spurlock was forever changed by the crash, his championship victory offering scant consolation for the friends and mentors he lost. At home, he found little sympathy, and at school he lashed out at a reporter who was filming girls cleaning out their best friends’ lockers.

“My dad said I just had to forget about it. I can’t. It’s right there in my face every day. I’ve always wondered, if that wreck hadn’t have happened, how would the events of my life have changed or been different?” Spurlock said. “There are still a lot of people that haven’t healed. It was so much to have all that death in your face as a young kid.”

That December, he left Whitefish and joined the Air Force, never to return to his hometown. He now lives in Utah and owns his own insurance company.

“That crash changed my perception on life. I realized I couldn’t take it for granted,” he said. “It’s crazy to have been a part of it. I still pack a lot of my memories of that night around. I sometimes have to do my own moment of silence. I feel like Mr. Withrow has been with me throughout my entire life.”