WHITEFISH – When the strobe-lit, polyester-clad disco scene of the 1970s arrived in the sleepy, blue-collar railroad and timber town of Whitefish, its tide of popularity was cresting in the big-city hotbeds that fostered the meteoric rise of club culture.

It was the summer of 1976, and the Queen of Disco, Donna Summer, was sizzling in sequins while the serial killer David Berkowitz terrorized New York City with a .44-caliber handgun, adopting the nickname “Son of Sam” and signaling an end to the summer-of-love hippie zeitgeist that dominated the ‘60s.

There were reportedly 10,000 discos in the U.S. – discos for roller skaters, discos for children and senior citizens, portable discos in shopping malls and Holiday Inns – and the dance craze was sustaining a fever pitch as Billboard’s weekly charts regularly featured a slate of disco songs.

The halcyon days were just alighting on this working-class ski town, and it would be years before disco reached its high-water mark and the wave came crashing down with Disco Demolition Nights and bumper stickers bearing the infamous anti-disco sentiment “Disco Sucks.”

The counterculture born of the 1960s wasn’t yet ready to wake up to its collective hangover or wink away the haze of the 1970s. In Whitefish, the effort to reforest clearcut-logged areas created scores of U.S. Forest Service jobs and drew hundreds of twenty-something hippies who could live on the cheap.

And just as the town was poised for a movement, along came the golden handshake of a flashy Canadian investor named Fraser Baalim, who hired a handful of contractors from a Denver, Colorado-based company called Lights Times Dimension (LTD) to build the state’s first discotheque, The Palm, and change the town forever.

“I was a 23-year-old disco-technician,” said Jim Blankenship, of Whitefish, who worked for LTD.

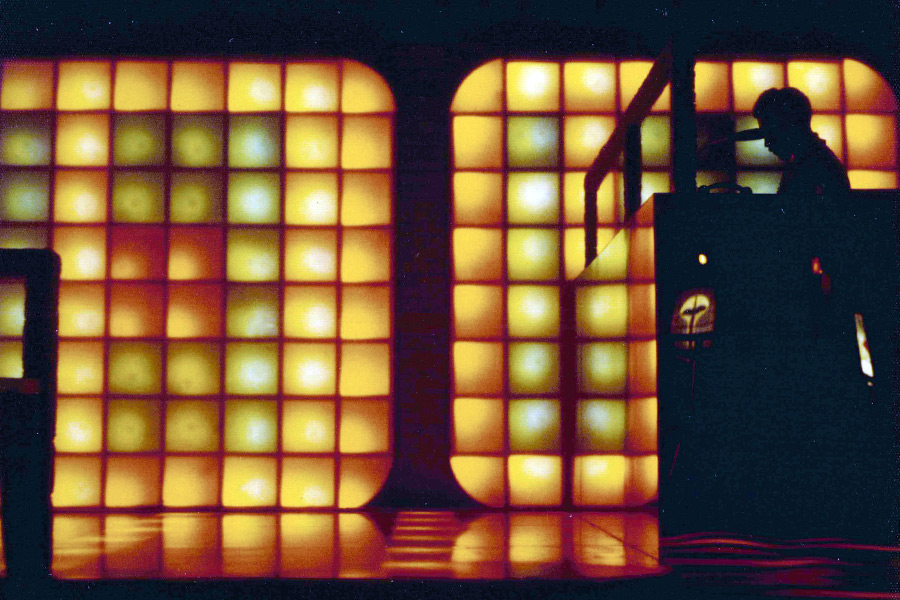

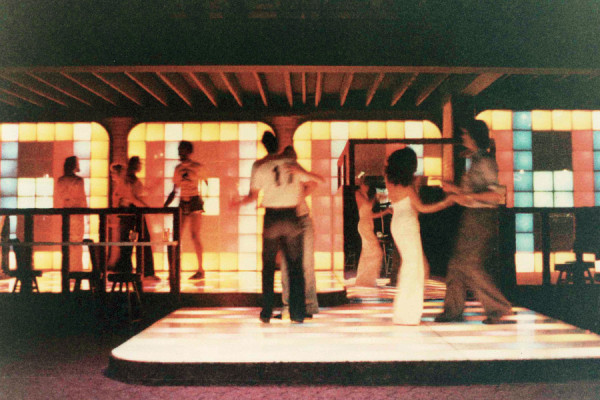

The company employed so-called “disco-technicians” to travel around the country remodeling buildings and constructing specialized discotheques, sound systems and dance floors, which were programmed to pulsate with fractal-like patterns in a myriad of lighted colors, flashing to the beat of the music.

“I had never been to Montana or heard of Whitefish, and when I got here I thought, ‘Really? This is where we’re building a discotheque? You’ve got to be kidding me,’” Blankenship said. “There was this old-boy community with a lot of loggers and railroaders at the bars, and all of a sudden there was this infusion of young people in white polyester suits pretending they were John Travolta. It changed the town.”

The Palm Hotel

In July 1976, Baalim purchased The Palm Hotel, which is now the Remington Bar and Casino, after he and his wife, Susan, completed a 9,000-mile tour of the United States and Mexico, scouring the countries for the perfect spot to build a discotheque. After considering places like Phoenix and Los Angeles, the Lethbridge, Alberta couple pointed their rig at Whitefish, where they had vacationed for years, loved the lake and the ski hill, and decided a discotheque would be a fine, if unlikely, fit.

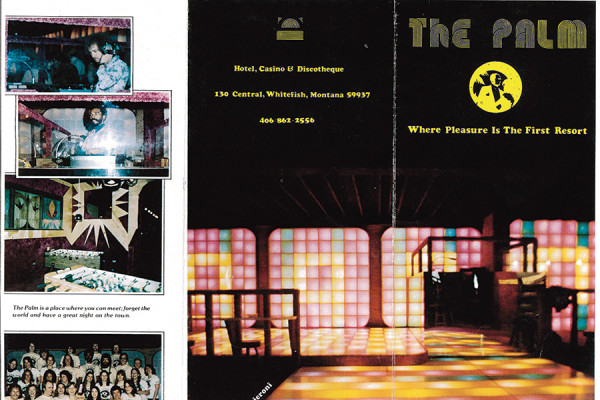

The Palm Hotel, Casino and Discotheque featured a $30,000 sound system and a three-level dance floor made of plexiglass. Covering the walls were four 60-square-foot light consoles, composed of eight-by-eight individual light panels that flashed in geometric patterns timed to the beat of the music. A disc jockey worked two turntables and a live drummer played suspended from a hanging stage.

The remodeling struck a 1930s lounge motif and cost more than $250,000, but Baalim opted to keep the hotel’s longtime name, The Palm, to evoke its textured history.

The structure was originally built in 1909 by Mokutaro Hori and was called the Hori Hotel. Hori arrived in the states from Japan penniless and worked as a houseboy for the Conrad family in Kalispell. Eventually, Charles Conrad gave him 10 acres in Whitefish.

With a $50,000 loan Hori opened a hotel, restaurant and bakery, as well as a ranch and agricultural farm. His beef and vegetables were awarded a blue ribbon in a contest and supplied the dining cars of the Great Northern Railway across the continent. Aya, Hori’s wife, warmly welcomed the railroad and lumberyard workers who lived hand-to-mouth, dishing out stews from the backdoor of her restaurant.

Meanwhile, Hori invited Sumo wrestlers from Japan, hosted a fireworks festival and planted Japanese cherry trees until he died of stomach cancer in 1931 at the age of 58.

“He became the preeminent businessman in Whitefish and was highly respected,” Jill Evans, of the Stumptown Historical Society, said. “At his funeral there were thousands of people.”

Five years ago, Evans nominated Hori to the Montana Cowboy Hall of Fame, and he was inducted.

During World War II, Aya continued to run the hotel, and hid Japanese refugees from detention camps, squirreling them away in rooms built beneath what would become the disco dance floor.

The Palm’s rich history bled into the nascent disco days beginning with the restoration, when builders discovered artifacts and antiques in the hotel’s basement rooms.

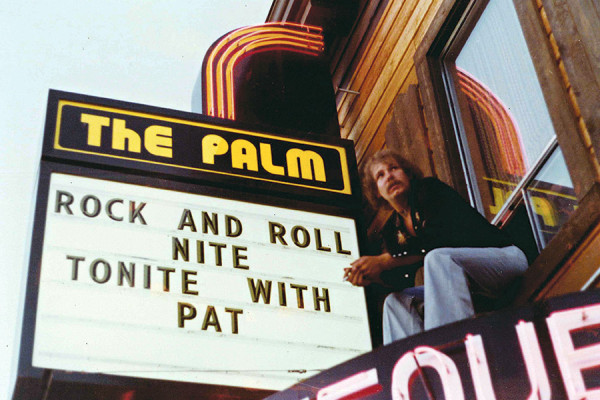

Pat Pieroni was living in Spokane, Washington and had just broken up with his girlfriend in the summer of 1976. He wanted a change of pace, and on a capricious whim settled on Whitefish, where he landed a job building the discotheque.

“I was kind of a lone ranger when I landed with that crew and got hired on. It was a unique period because the people we worked with were operating in a very high creative mode. We were just kind of flying by the seat of our pants. The place was ugly as hell until we started stripping it,” Pieroni recalled. “But as they started stripping everything back, we started finding things that were so cool – bottles, silverware, knickknacks, lamps and lanterns from the early 1900s. The metal ceilings were still intact with this ornate, stamped metal that curved on the corners, and we found this old trap door that led to the basement and there were dozens of shrink-wrapped boxes of Havana cigars from Cuba, old beer advertisements and calendars. And as we discovered these things, we built these cabinets with plexiglass on them and displayed all these artifacts across the back of the bar. We were working 18-hour days because we needed to have that thing open by January for the ski season, but we were having a lot of fun.”

Where Pleasure is the First Resort

Just before Christmas 1976, The Palm opened its doors to the public, unveiling its walls inlaid with geometric designs of white aspen and mirrored panels accenting reclaimed barn wood.

The Baalims decided to brand The Palm as a combined discotheque and casino, offering live poker and keno in the front of the bar and dancing in the back.

Its decadent motto was “Where Pleasure is the First Resort” and the combination drew a varied clientele from the outset.

“On the first night that The Palm opened, a girl named Bernice was working behind the bar with a beehive hairdo two-feet tall, and then there was this group of good old boys sipping blackberry brandy and smoking cigars at the poker table,” said Linda Roberts, one of The Palm’s managers. “It was like two worlds colliding. The town was pretty dead in the early ‘70s and The Palm changed it into what it is today. It was like an earthquake. We were a big deal.”

Local law enforcement took an immediate interest in The Palm, which was a new breed of bar for Whitefish. Blankenship recalls how the influx of employees – the disco hired 45 – quickly raised the vigilance of the police.

“They were on us like white on rice,” he said. “The town was full of cowboy bars and The Palm broke it loose.”

Lonnie Herman was Whitefish’s assistant police chief at the time and recalls The Palm’s seismic impact on the downtown scene.

“I remember when they built it. That was a big deal. There were people coming from all over – Idaho, Canada, California. It filled up downtown Whitefish. They really packed it in. It had that lighted dance floor that was all the rage. It was pretty impressive for its time,” Herman said. “Back then there was more of a country mentality … and then The Palm came along. That little gin mill kept us busy for a lot of years. It used to be quite an adventure. As far as a drinking, partying, pub-crawling, let’s-have-a-good-time crowd, they were it.”

Canadians began arriving in Whitefish by the busload, which stirred resentment in a ski town that prided itself for its anti-resort aesthetic. “Gut shoot ‘em at the border” was a popular saying, recalls Roberts, but they filled The Palm night after night, rankling locals but securing the discotheque as a new establishment in town.

“A lot of the scene when I got there was kind of poker games and country music,” Pieroni said. “These blue-collar guys would come to town and hoot and holler and then go back in the woods to work. But The Palm really brought out the ski scene and the Canadians. The Canadians started coming down like gangbusters. I think it changed the town immensely.”

It wasn’t uncommon for a half-dozen buses to unload Canadians on Friday and linger downtown for the entire weekend before departing on Sunday evening.

“The whole disco thing was brand new and it was all the rage and this guy Fraser Baalim built the only one in Whitefish, so we were dealing with a lot of people from a long way away who were coming here just for The Palm,” Herman said. “That was the draw, and people would come to town for these huge pub crawls. We’d have five or six busloads of them. It was just insane. They’d fill every bed in Whitefish and when Whitefish was full they’d fill Kalispell and Columbia Falls, too. We’d have four buses sitting in Whitefish and at 2 a.m. they’d stagger to their buses and go home. They skied, too, of course, but The Palm was certainly a huge draw in the downtown area.”

Do A Little Dance

Gary Cabell arrived in town shortly after The Palm opened and immediately began looking for a job. He’d worked briefly as a disc jockey for his college radio station, and The Palm was looking to hire someone after management had to fire its inaugural DJ.

“At one time someone did get busted for selling some Thai stick, I believe it was, out of the disco,” recalls John Macy, who worked as a bouncer at The Palm before becoming a DJ himself.

“I took Disco Doug’s place as a DJ,” Cabell said. “We started doing theme nights, like Ladies Night and Astrology Night. I think we started with Capricorn. I remember counting 125 women who came through the door on a Ladies Night. When it was going hot, it was really hot.”

The female bartenders and cocktail waitresses wore tight-fitting halter tops. Bras were discouraged, while exposed midriff and make-up were mandatory.

“We had to wear these ridiculous tops and carry the drinks on a cocktail tray, and they were always spilling down our tops because it was so packed,” Jan Metzmaker, one of The Palm’s first cocktail waitresses, said.

The DJ booth was filled with 2,000 record albums and two eight-foot tall speakers, and a marquee and reader board on the front of the building featured the classic, art deco font of the disco era.

“It was the nicest discotheque I’d ever been in,” Macy said. “It was state of the art. There was a sauna upstairs, and the hotel had sleeping rooms with bunk beds and dormitory-style bathrooms. But they were nice.”

The Palm’s signature cocktail was called the “Tropical Buzz” – a vodka concoction that tasted like a pina colada on steroids, served in a hurricane-shaped glass.

“It was one of these nightmarish drinks that has five types of liquor and a bunch of sugar and if you had five of those you were on your knees,” Macy said.

Packing the dance floor was effortless, Macy said, and while disco music figured prominently into the DJ’s repertoire, rock music and slow dances were also common.

“We played a lot of disco, but not exclusively disco,” Macy said. “Disco gets derided now, but it was just like any genre of music – some of it is really, really good. Of course, some of it is really bad. Donna Summer, Gloria Gaynor, the BeeGees, some of that stuff was really good. Some of it kind of stunk. But it didn’t matter. The dance floor was always packed. It was loaded. You could hardly get them to leave at 2 o’clock in the morning.”

In keeping with the spirit of the era, cocaine and hallucinogens were standard fare. So was promiscuous sex, and one evening a man disrobed in The Palm’s all-glass lobby, nothing but a potted frond concealing his nether-parts from passersby. It also wasn’t uncommon to begin an evening at The Palace, dance at The Palm until the bar closed, then party all night before heading back to The Palace for the bar’s 8 a.m. happy hour, which catered to railroaders just finishing their shift.

“We’d all be at The Palace and then someone would touch his palm and we’d just flood out the door and head to The Palm. That was the signal to everyone,” said Blankenship, whose signature dance move was known as the Blankenship Boogie.

“There were drugs there and the police always kept a wary eye on us, but nobody there was lawless,” Macy said. “I remember we had quite a presence, probably just because it was so different.”

“It wasn’t out of control or anything, but it could be overwhelming at times,” Herman said. “They kept us on our toes.”

Disco Sucks

And then, one day, people stopped showing up. The mirror balls quit spinning and shimmering, the dance floor quit luminescing and bellbottoms fell out of fashion.

“Boy, when it turned, it turned fast. It was like the faucet just turned off,” Pieroni said. “We maybe didn’t all love disco but we really loved what we created there. We were a family.”

Even after disco died – or, at least, changed its haircut and altered its cosmetic makeup – the influence of The Palm lives on in downtown Whitefish. But the “disco sucks” movement led to an implosion of the scene in the early 1980s, and by 1983 The Palm was bleeding money, and Baalim, who once entertained plans of opening a chain of discotheques in Montana, was forced to close the disco.

“That really tore Fraser apart,” Pieroni said. “He really loved that place. We all did.”

“It was short lived because disco was short lived,” Blankenship said. “I remember some local telling me that the disco ruined this town. That broke my heart.”

“The Palm ignited this town. It created the Whitefish that you see today,” Roberts said. “We were way ahead of our time.”

“People just quit coming in,” Cabell recalled. “It seemed like the whole scene just died. The ‘disco sucks’ movement took over and put an end to it. It’s funny, too, because now the clubs are doing the same thing.”

“Old Fraser Baalim sold it and it never was the same,” Herman said. “I don’t know why or what happened. It just kind of fell apart. Maybe the rage just faded and people got tired of it. It kind of simmered and simmered and slowed and slowed and eventually they turned off the lighted floor and it just went back to a regular bar. Ultimately they ripped the whole thing out.”

A few years ago, Roberts organized a reunion of The Palm and invited 39 of the 45 employees who worked there in various capacities; 36 of them showed up for a weekend of barhopping, and Roberts had The Palm’s original T-shirts reprinted.

“It was like a college experience. We all took care of each other. It was a really special time in Whitefish,” Roberts said.

Baalim never recovered from the death of The Palm, and his own death was memorialized at the reunion.

Blankenship, who came to Whitefish in July 1976 to help build The Palm, never left, and today is still working in construction.

“The Palm brought me here. When I first came here it was all I wanted,” he said. “Every other place was Disney World and Whitefish was the real world. Most of the people who were there in the 70s are still here. We just don’t have The Palm.”