WHITEFISH – For most of his life, Rocky Hoerner has been on the move. His ability and propensity to shift and adapt has been necessary at times, and a force of habit at others.

Moving without hesitation saved his life 14 years ago, when he was able to dodge multiple bullets fired from the gun of a notorious criminal in Columbia Falls, but the transient life that came next – two trials, the dissolution of a marriage, living in 33 places in 14 years – kept him in a sort of purgatory, stuck between fear of the past and the promise of the future.

Now, Hoerner, 57, has quit running. He’s quit covering his tracks for fear he or his family will wind up in the crosshairs again.

Joseph Aceto, the man who shot at Hoerner on May 22, 2000, died in Montana State Prison in May.

For Hoerner, Aceto’s death is a chance at a new life, one without the heavy mantle of fear and dread. It’s the feeling of spring’s warmth and green buds after a long, cold, bitter winter, or of coming up for air after staying underwater too long.

“All that weight, I didn’t ever realize it was there; it just went poof,” Hoerner said recently in his kitchen. “My art is just exploding. Now that it’s over completely, I’m going to get it all out there.”

It wasn’t until after the picture window in his Columbia Falls art gallery exploded in gunfire, after dodging bullets and hiding in the gallery’s office to call 911, after hearing three gunshots and screams from his girlfriend in the room next to him, that Hoerner realized what was happening.

A mere minute before, he and Eileen Holmquist had been working in his gallery, which had been open for four days. It was late, about 10 p.m., when Aceto had first driven by.

Aceto was a jilted ex of Holmquist’s, and had a history of violence. Hoerner walked out the door, and Aceto drove off. But a couple of hours later, around midnight, they noticed his car sitting in a nearby alley. Hoerner walked outside, ready to confront the man, when Aceto got out of his car, took a couple steps, then pulled a gun.

“I screamed ‘He’s got a gun!’” Hoerner said. “What saved my life is I wasn’t hesitating.”

Already running before Aceto fired his first shot, Hoerner hid behind a tree, and eventually made his way back into the gallery, somehow avoiding being shot by the many bullets loosed from Aceto’s gun.

After the picture window shattered, Hoerner hit the ground and rolled off to a partitioned office. Holmquist had already run inside and locked herself in a different room.

“He thought for sure he got me,” Hoerner said, which explained why Aceto turned his attention to Holmquist.

Hoerner remembers hearing three shots – two Aceto fired at the door, and one he fired once he was in the room with Holmquist. With the final bullet in the gun, Aceto put the barrel to her head and forced her to drive up the North Fork.

As a child, Hoerner grew up in Kalispell. His parents had split up when he was young, and his mother, Frances Cole, was a bartender at the old Log Cabin Bar.

“She’d have to leave me alone, she couldn’t afford a babysitter,” Hoerner said. “So I would draw.”

He figures they moved about every three months. Alcohol was a problem for her, he said, and by the time he was 16, he was taken from her care and placed with a foster family.

The uprooted childhood meant he made the rounds at most of the schools in the county, and it helped in high school when he would get to a kegger or the drive-in movie theater and know people from every school.

“That was an upside,” he said. “But it was also no stability – zero.”

Hoerner would eventually graduate from Columbia Falls High School in 1975, and started working for Thomas Printing as an artist. He reconnected with his mother when he was 19.

She was married, and Hoerner said it was the calmest he remembers seeing her. She died of a brain hemorrhage later that year, at the age of 37.

His father, George Hoerner, wasn’t involved in his life much at that time. In an interview, George Hoerner said he tried to reach his son, but it didn’t work out. He didn’t know that Rocky’s life had been so transitory, and regrets that.

Rocky would visit on the weekends, where he connected with his lifelong friend, Dave LaValley, who lived next door to Rocky’s dad and sisters.

LaValley remembers a tough early life for his friend, but that art was one of the only constants in Hoerner’s life. When they were kids and didn’t have money, LaValley would enter the fair competition to catch a greased pig, and with his winnings would buy Playdoh.

Hoerner would make outrageous creations with it, LaValley said.

“He was good at it, even then,” LaValley said.

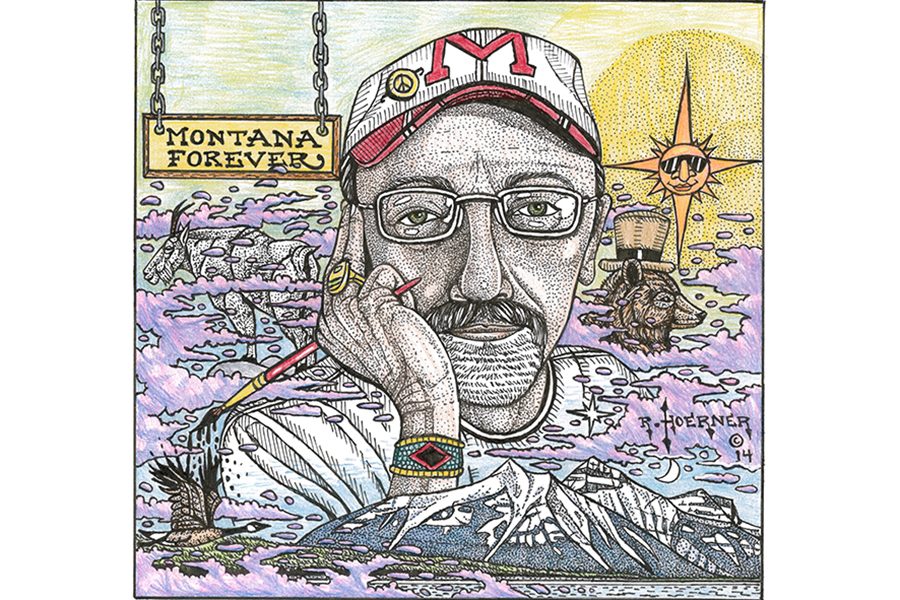

When Hoerner was 14, he sold his first piece of art. He was finding his style, which now includes extremely detailed pen and ink drawings.

By the 1980s, his art was growing quickly. He was selected for the Western Heritage Art Show in Great Falls, and remembers being the youngest artist invited to the event. He also hosted the Rocky Hoerner Picture Show at the Mountain Mall in Whitefish, and a couple of successful shows at the old Paul Bunyan Bar in Columbia Falls.

Hoerner’s series of mountain man pieces were shown worldwide. He moved to Boise at the end of the ‘80s, but couldn’t stay away from Montana for long. He married his first wife in 1992, and opened a screen-printing shop with her in 1993.

Their daughter was born in 1995. Hoerner said this was a happy time in his life, but the stability didn’t last; the couple split in 1998 and Hoerner was back to living in his trailer.

Despite the dissolution of his marriage, Hoerner said he was productive in his art.

“I’ve spent most of my life alone, so it’s kind of a necessity at times,” he said.

After a brief stint in Spokane to live with his sister, he moved back to the Flathead. He traded art for a 1959 Airstream trailer, and began dreaming big again.

“I thought, ‘I’ve got to get a gallery,’” Hoerner said.

With a loan in the works and a new location in Columbia Falls, Hoerner was about two weeks into getting the building ready when his grandmother died. After the funeral, he went down to the Sportsmen’s Bar and got a beer and a sandwich.

That’s where he would meet Eileen Holmquist.

“All of a sudden, Eileen walked by and I was like, ‘whoa,’” Hoerner said.

She had come to the bar with a boyfriend, but she and Hoerner struck up a conversation. He learned that she was only with the guy because she was hiding from Aceto, whom she had been seeing before.

Within a few days, Eileen ended it with her boyfriend and was working with Hoerner at his gallery. She was also a talented artist, he said, into drawing surreal scenes with pen and ink.

Joseph Aceto moved to the Flathead in 1999 as part of the federal witness protection program. He was using the name Joseph Balino, and had a lengthy criminal record by the time he set foot in the valley.

Law enforcement had him under surveillance in 1976 in connection with a bombing in Maine, and he was arrested and charged after he crashed his car and officers found dynamite.

He pleaded guilty to an explosives charge in connection with bombing and bank robberies in New Hampshire and Maine, and testified against his co-conspirators.

After only three years in prison, he was released under the witness protection program, but wound up in prison in Arkansas for a series of robberies and burglaries. There, he would be charged with the stabbing murder of a fellow inmate and receive another 25 years, but Aceto was released in 1997 to federal authorities.

In his court testimony, Aceto said the night of the shooting, he had been at the Blue Moon in Columbia Falls, drinking with another of Holmquist’s ex-boyfriends, when he learned about her whereabouts with Hoerner.

He testified that he went to the gallery with the intent to scare Hoerner, not to kill anybody.

When the police finally arrived at the gallery, the adrenaline had left Hoerner’s system and he was shaking.

“All I could think was ‘she’s dead,’” Hoerner said.

That was apparently what Holmquist was thinking about Hoerner, because when they were finally reunited after two days, she told Hoerner that Aceto had been telling her, “I killed that son of a bitch.”

The days Holmquist spent with Aceto in the North Fork were brutal, according to Hoerner. She said he raped and beat her, though rape charges were never filed in this case. She was found near Big Creek, alone.

Wendy Ostrom Price was working at radio station KOFI during the manhunt for Aceto, and remembers meeting with then-Sheriff Jim Dupont to talk to the wanted man on the radio. Holmquist had apparently said KOFI was the only station they could hear up in the North Fork.

“We talked to him through the radio. I said, ‘Mr. Aceto, if you are listening,’ or something to that effect, ‘no one’s been seriously hurt, this can end peacefully,’” she said. “We were trying to get him to surrender.”

While waiting for Aceto to exit the forest, Hoerner and Holmquist were holed up at a friend’s house on Whitefish Lake. They were ecstatic to see one another at the hospital after she was found, he said, because they were both convinced the other was dead.

But once they had settled into the house, she started to break down. He remembers seeing the marks Aceto had made on her.

“She had bruises everywhere,” Hoerner said.

Law enforcement captured Aceto the following day. Though the manhunt was over, the years-long ordeal of trying Joe Aceto for his crimes was just beginning.

Media attention zeroed in on Hoerner and Holmquist, as well as their families. Hoerner remembers Holmquist’s young daughters fending off reporters at their elementary school, and his ex-wife and daughter doing the same.

The scrutiny leading up to the trial was intense, he said, and there was also the fear that Aceto could get to his family through nefarious connections. He tried to restart the gallery, but it failed.

“Everybody who came in wanted to talk about the shooting,” Hoerner said. “I lost everything I put into it.”

The fallout from the shooting and kidnapping was also too much for Holmquist and Hoerner’s relationship, and the couple split. She moved to Wyoming to work with her father, he said, and he got a job at Semitool.

“We were happy as hell before the shooting,” Hoerner said. “But I just didn’t know how to handle that, you know?”

The trial was postponed for two years. When it finally got started in 2002, Aceto was charged with two counts of attempted deliberate homicide and one count of kidnapping.

He represented himself during the trial, and got frustrated during his cross-examination of Holmquist. He and the judge, Ted Lympus, started arguing, and Aceto exploded, throwing his file at the judge and yelling profanities.

Ostrom Price said it was a bizarre trial, especially with the outburst, and from then on, Aceto stayed in his cell, where he watched the proceedings via closed circuit television.

“He threw a fit in the courtroom; they ended up having to remove him,” Ostrom Price said. “He had to proceed electronically, because he could not behave in a court of law.”

She also remembers Holmquist as brave on the stand, facing the man who had kidnapped her.

Aceto’s standby public defender had to step in. Aceto was found guilty, and sentenced to more than 200 years in prison.

Hoerner said he met up with Holmquist after the trial at the Packers Roost in Coram, to celebrate their victory. Not long after, she was found dead, with an apparent self-inflicted gunshot to the head.

“That was really hard, there,” Hoerner said. “She was so traumatized.”

Hoerner kept moving, trying to rebuild his life. In 2004, he met the woman who would become his second wife, and moved to Libby with her. But soon after, he found out the Montana Supreme Court had granted Aceto another trial, after Aceto appealed his conviction, claiming the judge had violated his right to be present for all court proceedings.

It was a tough blow, especially since Holmquist was already gone. Hoerner was the main witness, and the fear of Aceto’s potential retaliation grew.

“I would have never gotten married, I would have never gotten into a relationship, if I’d known it was going to happen again,” he said.

His father said it was a hard time for Rocky, who was at one point hospitalized for illness and depression. But the safe place for Hoerner was always with his pen and paper, and his art was where he went to decompress.

“That’s what kept his mind away from that for a while, when he got into his art,” George Hoerner said.

Hoerner’s second marriage ended and he moved back to the Flathead in time for the second trial in 2006. Aceto was eventually convicted, and sentenced to 220 years in prison, without eligibility for parole.

In the eight years that followed, Hoerner said he tried to get his life back on track. The economy crashed in 2009, taking much of the art market with it, and he took a part-time job at the Alpine Village Market in Whitefish, where he still works and sells art.

It wasn’t until May of this year that he felt closure. He was standing in line at a grocery store, and saw a headline about Aceto. First he felt familiar fear and apprehension.

“I thought he got another trial,” Hoerner said.

But further reading showed the criminal had died of an illness in prison. Hoerner said he started cheering, and got odd looks from people around him until he could explain his joy. They joined in.

The relief of not having to worry about Aceto anymore is like a balm on a burn, one that he didn’t know was still hampering his life.

“(The relief) just keeps happening, like waves over me,” Hoerner said.

Since the burden of fear has been lifted, he’s been able to take stock of his life. He didn’t realize how much energy he still expended on Aceto, and how much space it took up in his mind.

Now, his art is flowing, like an undammed river. It’s worth focusing on again, he said, and he’s started dreaming of his own gallery once more.

“I feel like I just came alive again,” he said. “I’ve got a lot of purpose left.”

LaValley, his friend of 50 years, said he’s seen a positive change in Hoerner since the news of Aceto’s passing.

“He’s totally found his center. He’s just really gotten back into his artwork. He wishes he could pursue it full time,” LaValley said. “I’m just really proud of what he’s been doing.”

George Hoerner also said he’s seen his son blossom, and find a stability in life he didn’t have before.

“I think right now he’s probably feeling better about things,” George Hoerner said. “He’s a pretty good artist, you know.”

Hoerner said he realized he and his daughter have drifted apart, that he wasn’t the father he should have been during that time. Now, he has made it his priority to work on their relationship.

He is also trying to get his name out to the public again, now that he doesn’t have to worry about being caught unaware by people with deadly intentions. He’s settled into a house in Whitefish, and has started pulling out his art and arranging it in his garage.

In short, Hoerner has stopped moving, and started living again.

“I couldn’t be me to anyone during that time,” he said of the last 14 years. “It feels so good now; I want to get my name out there.”