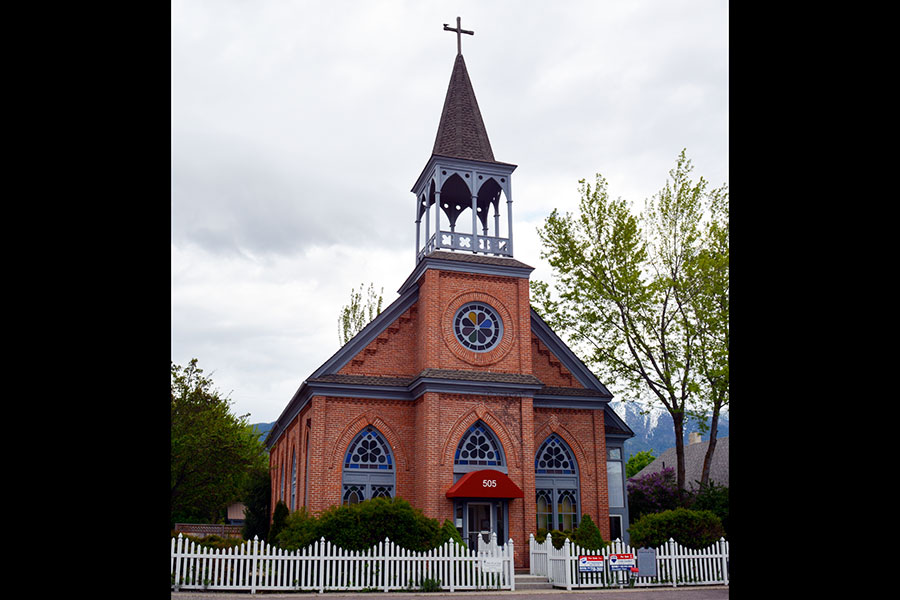

Not to be confused with the new St. Richard’s church nearby, this Gothic brick church at 505 W. Fourth Ave. in Columbia Falls was the original Saint Richard’s. It was the first and largest of its kind in Northwest Montana when it was built in 1891. It was also where the first public school classes were taught in Columbia Falls, with pupils on school days and parishioners on Sundays.

In August 1891, The Columbian newspaper heralded the future of Columbia Falls and declared “A City of Churches Is What Columbia Falls Will Be in the Near Future.” Yet for the moment, the town had more to do with commerce and railroading than churches and religion. After all, this was a western town in its early hey-day, when stores of every kind lined Nucleus Avenue (although perhaps cigars, wine, and whiskey were most easily had). The newspaper also told of a common perspective of the day: “No man of family desires to live in a community where there are no churches, and many men judge a city by its church buildings and schools.”

And with such a notion in mind, St. Richard’s church indeed served the town and the local community well. But there’s something even more “local” about the church. If you’ve taken the time to appreciate the early brick buildings in the Flathead Valley, you may have noticed that some are made with bricks of a distinct, red-orange tone. Their unique color comes from an equally unique source: the clay along the banks of the Flathead River. In this case, the brothers Byrnes took the clay and fired it at a brickyard in Columbia Falls near the river.

Of course, the color of the bricks is hardly the only distinctive feature of this seemingly restrained, (western) Gothic-style church. And while at first glance, aside from its fanciful steeple, and the even more uplifting spire atop it, the church may seem like a “plain” brick building. Yet a closer look reveals some rather intricate detailing, such as the dentil trimming, the accents around the arched, stained-glass windows – all done with brick made nearly 125 years ago.

And it is perhaps the stained glass windows, in arched Gothic design that most prominently accentuate the church with unique character. The simplicity of the window design is likewise deceiving. The windows and the process of constructing them are also rather unique. Quite so in fact, as Father Honore B. Allaeys, who supervised the initial construction of the church (costing some $5,000 at the time), patented the “process of making mosaics” that was used for the original, decorative windows that once adorned the church [see U.S. Patent No. 490,467].

The interior of the church was also remarkable as well. While there was a raised pulpit, a choir loft with fanciful balustrades at the narthex, perhaps the most defining original feature was that it was once just a large open space – with a vaulted Gothic arch and “pressed-tin” ceiling.

However, as times change, so do places and spaces. While historically speaking, the church was a place of firsts, it was also a place of last rites (and countless ceremonies in between). The parish eventually outgrew the church after WWII, and a newer, larger church was deemed necessary. The archdiocese laid plans for a new church and sold this one around 1958. Since then, it’s been private property, in one form or another. Yet despite the changing times, and more than a few alterations and renovations, the church remains steadfast to much of its original design and form.

Jaix Chaix is a columnist and author of Flathead Valley Landmarks and other local history books that are available for sale at the Flathead Beacon at 17 Main St. in Kalispell.