MANY GLACIER – Anyone who has worked at or spent any substantial amount of time at the Many Glacier Hotel will tell you the same thing: It’s a special place with a rich and unique history.

Diane Sine discovered this as a kid in the 1970s on summer camping trips with her family. The magical pull of the place was so strong she eventually landed a job there as a waitress and later as a seasonal park ranger. She even married on the shores of Swiftcurrent Lake.

The late actor-comedian Robin Williams realized it when filming “What Dreams May Come” in the late ‘90s at the Many Glacier Hotel. He looked at the mountains that surround the pristine lake and mused, “If this isn’t God’s backyard, then He certainly lives nearby.”

And Louis W. Hill, the railroad baron turned park promoter, realized it when he visited this remote piece of land more than a century ago and declared that a hotel would be built there deserving the title “Showplace of the Rockies.”

This summer, the Many Glacier Hotel celebrates 100 years as one of the crown jewels of Glacier National Park. For more than a century, the massive hotel has withstood the ravages of time, floods and fire, all the while enticing people with its legend and lore.

“There is a magic about this place,” Sine said. “That’s why I decided as a kid that I wanted to work here.”

Louis W. Hill saw opportunity almost the moment President William Howard Taft signed legislation creating Glacier National Park in May 1910. In the late 1800s and early 1900s, railroads across the West were using the newly established parks as a marketing tool to lure passengers aboard their trains. The Northern Pacific Railway was doing it with Yellowstone, the Southern Pacific Railroad was doing it at Yosemite and the Atchison, Topeka and Santa Fe Railway was doing it with the Grand Canyon.

Before the ink of Taft’s signature was dry, Hill and the Great Northern began promoting and developing the park. In order to attract wealthy easterners who often vacationed in Europe, the railroad pushed a marketing campaign using the slogan “See America First” and began likening Glacier to the “American Alps.” To play on that theme, the railroad established a system of Swiss-style chalets in the backcountry. It also built two massive luxury hotels at East Glacier Park and Many Glacier. The hotels would be where visitors began and ended their backcountry chalet tour.

Construction of the Many Glacier Hotel began in 1914. Like the other structures in the park, the Many Glacier Hotel was built with Swiss influences to provide visitors the feel that they were in Europe and not the wilds of Montana. The most prominent features of the hotel are the 20 Douglas fir pillars brought in from Oregon, which can also be found at the Glacier Park Lodge. Unlike the ones at East Glacier Park that still have their bark, the pillars at Many Glacier are bare. That’s because they were dragged 50 miles from Browning, where they were unloaded from railroad flatcars, to Many Glacier. According to historian and author Ray Djuff, teams of 16 horses would drag supplies to the construction site on a trip that would take up to five days.

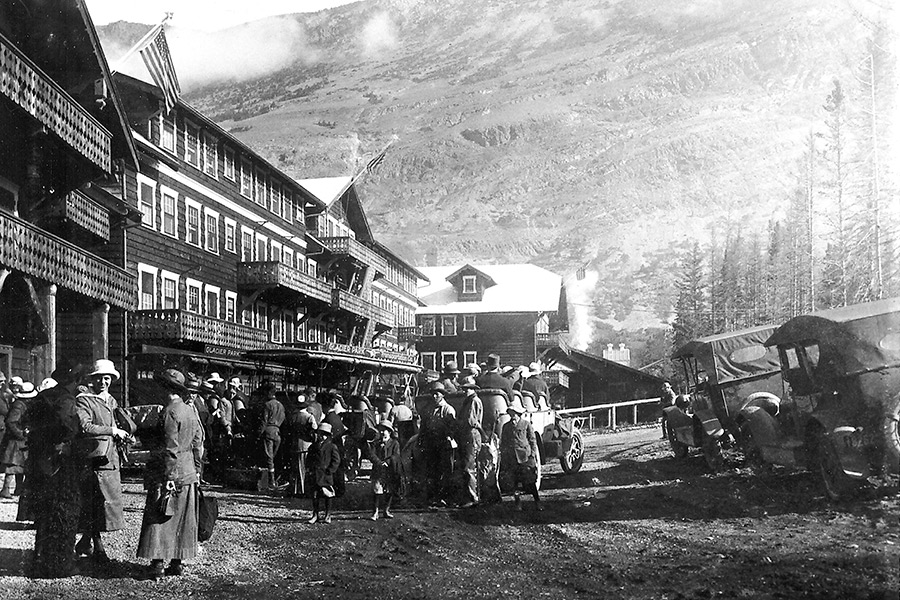

More than 400 people – most of them earning about 30 cents an hour – worked on the hotel through the winter. When it opened on July 4, 1915, it was billed as one of the grandest hotels in the West. That year, nearly half of the 13,000 people who visited the park stayed at Many Glacier. Two years later, the hotel expanded, making it the largest in Montana with more than 200 rooms. The hotel had numerous amenities, including a shoeshine stand, a tailor, barber and even a telephone in every room. Room rates started at $4 per person and guests could pay an extra dollar if they wanted a room with a bath.

While most guests enjoyed a restful and relaxing stay at the hotel, a few were not as lucky. In August 1936, the hotel almost burned to the ground when the Heaven’s Peak fire ran down the Swiftcurrent Valley. After helping evacuate guests, hotel employees worked through the night to keep the wood structure wet and doused spot fires that cropped up around it. While the hotel was spared, numerous surrounding structures were not. The morning after the fire, the hotel manager telegraphed Great Northern headquarters in St. Paul, Minnesota to tell them that the hotel had been saved. Railroad officials came back with a one-word response: “Why?” With the Great Depression hurting ticket sales, it seems the railroad could have cut their losses if the massive hotel had burned.

Less than 30 years later, in June 1964, three feet of floodwater inundated the first floor of the hotel. Amazingly, despite the flood, the hotel opened before the end of the month.

Perhaps the biggest threat to the hotel in its century of existence wasn’t fire or flood, but rather time itself. By the late 1990s, the hotel was in deplorable condition and it was slowly falling into the lake. Faced with millions of dollars’ worth of repairs, some suggested it should be torn down, including former President Bill Clinton’s Secretary of the Interior Bruce Babbitt, who told a U.S. Senate committee that he would take care of the old hotel “with a can of gasoline and a match.”

Despite Babbitt’s suggestion, in 2001 the National Park Service began a multi-million dollar project to renovate the hotel, which is now a National Historic Landmark. In the 15 years since, the Park Service has continued to make improvements to the structure so that it will last for years to come. The Park Service is also partnering with the Glacier National Park Conservancy and private donors to restore some of the building’s “character-defining features,” including an iconic spiral staircase that was removed in the 1950s and Oriental lighting that was a prominent fixture in the lobby in the 1910s.

The hotel’s current operator, Xanterra Parks and Resorts, is also making efforts to bring back some of the traditions that made the hotel so special, including musical performances put on by the employees. From the 1960s to the 1980s, hotel managers recruited drama and music students from around the country to work at Many Glacier. Diane Sine was hired in 1980 as a singing waitress and said that employees performed or practiced seven nights a week. At the end of every summer, they would put on a Broadway musical for guests.

Djuff, the Calgary-based historian who has helped produce nine books on Glacier and its historic hotels, said it is amazing the Many Glacier Hotel has withstood the test of time. He said it is a testament to the work of people like Hill and others who helped develop the park.

“These facilities are as loved today as they were 100 years ago and that is an amazing legacy,” Djuff said. “That’s a legacy that Louis Hill would be proud off.”

The Many Glacier Hotel Through the Years

1910: President Taft signs legislation creating Glacier National Park.

1911: The Great Northern Railway erects a teepee tent camp on the shores of Swiftcurrent Lake, then known as McDermott Lake.

1912: The railway builds a group of chalets to house more guests.

1913: A sawmill is built at Many Glacier to help construct the proposed hotel.

1914: Construction begins on the Many Glacier Hotel.

1915: Many Glacier Hotel opens on July 4. Nearly half of the park’s 13,000 visitors stay at Many Glacier that year.

1917: The railway expands the hotel making it the largest in Montana.

1925: National Park Service Director Stephen Mather comes to Many Glacier and personally blows up the sawmill that was used to build the hotel because he thought it was an eyesore. He tells guests the explosion was a birthday surprise for his daughter but the railroad is furious.

1934: President Franklin D. Roosevelt comes to Many Glacier for lunch as part of his tour of Glacier National Park.

1936: The Heavens Peak Fire nearly burns down the hotel but employees work through the night to save it.

1943 – 1945: The Many Glacier Hotel and other lodges in the park are closed during World War II.

1960: The National Governor’s Conference is held in Many Glacier. To deal with the influx of guests, the hotel orders an extra 106 cases of liquor.

1964: The first floor of the hotel is inundated with water during the Flood of 1964.

1987: The Many Glacier Hotel is listed as a National Historic Landmark.

1997: Robin Williams comes to Many Glacier to film a scene for “What Dreams May Come.”

2000: Faced with millions of dollars worth of repairs, Secretary of the Interior Bruce Babbitt tells the U.S. Senate he can take care of the hotel “with a can of gasoline and a match.”

2001: The National Park Service begins extensive renovations to protect the hotel.

See It For Yourself

Every day at 4 p.m. during the summer, a Glacier National Park ranger leads visitors on a free historic tour of the Many Glacier Hotel. The tour takes about an hour and starts inside the hotel lobby. For more information, visit www.nps.gov/glac.