Shadow of a Doubt

Richard Raugust is serving life in prison for the murder of his best friend, a cold-blooded crime he insists he didn't commit. In the face of new evidence, he hopes to finally prove his innocence.

By Tristan Scott

DEER LODGE – If anything’s clear it’s that a piece of Richard Raugust is somewhere else, someplace tangent to Trout Creek, Montana, July of 1997, a summer so vivid and transforming that right now it happens to be a detail about the trees that chokes him with grief rather than a stranger’s questions about the cold-blooded murder of his best friend.

Raugust came to Trout Creek because of the allure of high mountains, braided, blue ribbon trout streams and thick, verdant forests of green. And he came because of Joe Tash, the man he’s in prison for killing.

The two men met as boys growing up in northern California and, nearly 20 years later, arrived in northwest Montana, Tash having encouraged Raugust to join him at a remote campsite near the Clark Fork River after falling on hard times in the wake of his father’s death.

Eager for his friend’s company and knowing his affinity for the forests, Tash told him about the trees.

“He was my best friend. He knew I liked big mountains and dense forests, and when I asked him about the trees he told me, ‘Some of them, you can’t even see through them,’” Raugust says, his head bowed and his eyes squeezed tight as he recalls Tash’s enthusiasm for the newfound paradise.

Reuniting at Tash’s father’s funeral, the summons to Montana betrayed a desperate hopefulness, akin to a prospector invoking the specter of gold, the sincerity of Tash’s awe palpable as Raugust barely makes out the words, each syllable cracking with remorse.

He’s dressed now in nondescript prison-scrub beige, the smock-like cotton garb a few shades darker than the bleak wall of whitewashed cinderblock behind him, his 6-foot-4-inch frame cast against it in stark relief, his blue eyes bright, obscured only by a watery sheen that doesn’t recede.

“I came up here to help Joe, to be near Joe,” he says. “And I just fell in love with the trees.”

Raugust was a few years younger than Tash when he came across the teenager duck hunting on a small lake that bisects two cattle ranches near Mount Shasta, California. He’d heard gunshots and went along with a ranch hand to investigate, thinking it was trespassers. Instead, they found Tash, just outside the fence line, winging teals off the shore.

They became fast friends and over the next decade-and-a-half roomed together at a ruck of houses, including the home of Ken Bonner, the ranch hand, always keeping in close touch, even when Raugust joined the Army.

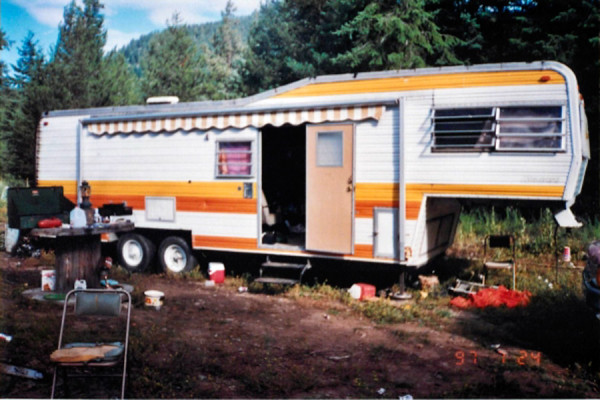

In 1997, they found tenuous purchase on a postage stamp of land in Northwest Montana, living in Raugust’s trailer at a campsite up Swamp Creek in Sanders County, off of Highway 200 northwest of Trout Creek, between Thompson Falls and the Idaho border. To make ends meet, they cobbled together logging and construction jobs. They frittered away time drinking at the Naughty Pine Saloon with a crew of locals, they fished and they smoked a bit of marijuana.

But in the 18 years he’s been in prison, there have been no mountains, no trout or trees, and, most significantly, no Tash, whose gruesome death on the morning of July 24 earned Raugust a life sentence in Deer Lodge. It’s a tough existence for anyone, but for Raugust, who says he’s as sure of his innocence as he is of the bond he shared with Tash, it’s a waking nightmare.

“It can crush you,” he says. “I’ve never used a cell phone or been on the Internet, I’ve been in here for so long.”

And yet, he’s optimistic.

From the moment of his arrest, the 49-year-old inmate at the Montana State Prison in Deer Lodge has insisted that he did not commit the murder, that it wasn’t him who took Tash’s life with a single-barrel shotgun blast to the head while he lay in bed, unconscious and defenseless. He claims he wasn’t even present at the crime scene; that he was sleeping on an acquaintance’s living room floor in Trout Creek that night, catching a few hours’ sleep at Rick Scarborough’s before an early-morning painting gig, passed out when the report of buckshot ripped across the Swamp Creek campsite, shattering the quiet of the dawn and setting into motion a chain of events that form the substance of his 18-year resolve to clear his name.

In recent years, a legal team assembled by the Montana Innocence Project has been mounting a case for Raugust’s innocence, fighting to secure a new murder trial by arguing that if jurors heard newly presented evidence that has emerged since Raugust’s conviction they would not reasonably believe he could have committed the crime, that the facts support his alibi, and that key state witnesses – including the man they say pulled the trigger – colluded to spin a web of lies, framing Raugust for Tash’s murder.

The guilty verdict was handed down in March 1998 by a Sanders County jury, which sat deadlocked for 10 hours before reaching a unanimous decision late at night, though some jurors, including the jury foreperson, say they weren’t convinced of Raugust’s guilt, that they capitulated only after the judge instructed them that a new trial would be too costly for the state and county to bear – a statement omitted from the trial transcript but recalled by, among others present in the courtroom, Mary Harker, the pastor of the Whitepine Community United Methodist Church in Trout Creek, who served as foreperson of the jury.

“I do remember the judge saying it would be too expensive and costly to hold another trial and the county could not afford it. I considered this in making my decision, and I remember the jury talked about the expense of a new trial, which was one of the pressures that led me to vote to convict Richard Raugust even though I believed the evidence presented at trial did not prove him guilty beyond a reasonable doubt,” Harker explained in a sworn affidavit. “The instructions given to us by the judge did not leave me with the belief I could disagree with the rest of the jury, the way the judge put it, it seemed like a lost cause.

“This has been on my mind and on my heart ever since that jury service,” she continued. “It rises up and troubles me in the night. I was shocked at the way it ended and thought it was a miscarriage of justice.”

The successful prosecution that put Raugust behind bars was based in large part on the eyewitness testimony of Rory Ross, the man who Raugust’s legal team asserts is the true killer.

The new evidence challenges the key testimony provided by Ross, who told the court he saw Raugust kill Tash, and theorizes that Ross collaborated with Scarborough to cover up the murder and pin it on Raugust – a theory prosecutors staunchly oppose.

According to Ross, he had been drinking with Raugust and Tash at the Naughty Pine on the night of July 23. They’d planned a barbecue earlier in the day, back at the Swamp Creek trailer site, and that afternoon headed to town for beer and chicken before stopping in at the bar owned then by Audie Hanley, which they ultimately closed down, inviting a lingering late-night clientele over for the party to continue drinking.

Only Randy Fisher acquiesced, and after sussing out a few details across the highway in the old Miller’s Market parking lot, Ross aimed his white 1985 AMC Eagle north toward Swamp Creek and peeled out with Tash riding shotgun, Raugust in the backseat and Fisher in tow in his own vehicle, which would ultimately break down, thus precluding a second witness to the murder.

Back at the trailer up Swamp Creek, Ross says the men were drinking and smoking marijuana when, at some point, Raugust and Tash started arguing because Raugust wanted to smoke another joint; Tash told him no, that he was running low on bud.

Ross told jurors that Raugust went outside the trailer and that he, Ross, went to sleep on the couch. He was awake, however, when he says Raugust re-entered the trailer, held a long gun over a sleeping Tash and fired once at the man’s head.

The details of what followed are wildly divergent, strung like a helix between Ross’ testimony and the alibi that Raugust swears by, and which his attorneys say is bolstered by a growing body of evidence.

What’s undisputed is that Raugust was arrested later that morning while painting and restoring Maret Brown’s trailer, at a work site along the highway at White Pine, southeast of Trout Creek. Witnesses said he appeared “dumbfounded” when a sheriff’s deputy arrived and told him he was under arrest for the murder of his best friend. Witness Tracy Anderson says she’d been visiting with Raugust for an hour-and-a-half that morning while he worked, and that he acted “totally normal.” She said he acted sober, friendly and did not smell of alcohol or smoke – a statement relevant to the case because there had been a campfire at the Swamp Creek site the night prior, as well as a burning slash pile used to destroy the murder weapon and burn a portion of Raugust’s camper.

He painted until noon, when police arrived to arrest him for the murder; even the arresting officer confirmed that when he told Raugust that Tash was dead, his reaction was disbelief and bewilderment.

In 2009 the Montana Innocence Project began investigating the case and three years later, after a lengthy private investigation, the nonprofit organization began its effort to exonerate the man in earnest, filing a petition for post-conviction relief in Sanders County District Court and demanding a new trial.

As the defense team looks to clear the necessary legal hurdles to open the floodgates on the new evidence and retry the case, the effort has been opposed at every turn by the state, with Sanders County Attorney Robert Zimmerman calling the new evidence dubious and born of witnesses who lack credibility, even while those same witnesses were presented by the state as credible at trial, a point Raugust’s legal team says amounts to a double standard.

Last December, attorneys with the Innocence Project presented newly discovered evidence in the case to Sanders County District Judge James Wheelis at an evidentiary hearing, and last month finished briefing the court in the complexly layered case.

In the coming weeks or months, Wheelis will make a decision on whether to grant or deny Raugust a new deliberate homicide trial. Regardless of his decision, it will almost certainly be appealed.

At the center of the Innocence Project’s case for a new trial is Raugust’s alibi, which the legal team says is supported by newly discovered evidence, and that the only testimony undermining it at trial was that of Ross and Rick Scarborough, at whose home Raugust says he slept.

Witnesses confirm and Scarborough admits that he drove Raugust to work at Maret Brown’s house on July 24, but Scarborough said at trial that he did so only after seeing Raugust walking down the highway toward his home at 5:30 a.m., about 30 minutes after Tash’s time of death. He says he loaded his children in his minivan and took Raugust to work, then drove to Thompson Falls to look for a new rental place.

Statements from Scarborough’s brother, Tom Scarborough, who died in prison while serving a sentence for a Lake County murder that occurred around the same time as Tash’s, and in which both Ross and Rick Scarborough were implicated, accuses Rick of lying about the veracity of Raugust’s alibi at the behest of Ross. He says that Ross confessed to murdering Tash on multiple occasions through the years, and that his brother told him that Ross’ motive was to nullify a drug debt to Tash and steal the man’s marijuana, which was never recovered but which numerous witnesses report seeing at the Naughty Pine.

Rick allegedly told Tom that “Rory put a serious case of the hurt on this guy” with a shotgun loaded with buckshot and that “we (Rick and Rory) made up the whole story,” according to the case materials.

Another critical piece of testimony that supported the prosecution’s theory was that of former Sanders County Sheriff’s Deputy Wayne Abbey, who performed a bar check at the Naughty Pine Saloon around closing time on the morning of the murder and encountered Tash, Ross, Raugust, and Fisher.

Abbey said he was in the bar visiting with the owner and saw Ross’ AMC Eagle across the street parked alongside Fisher’s car. He wondered what the men were up to, and then returned to his coffee and conversation.

But in later interviews with investigators and attorneys from the Innocence Project, Abbey said he glanced out the window again and saw Ross’ car stop briefly about 200 yards down the highway. He watched as the brake lights came on and the dome light illuminated before Ross again sped off.

Abbey said that while he couldn’t make out whether or not someone got out of the car, it happened quickly, in about the time required to perform “a Chinese fire drill.”

Attorneys for Raugust says it’s a key piece of evidence supporting his alibi that he hopped out of Ross’ car near the intersection of Highway 200 and Fir Street after having second thoughts about the late-night party; knowing he had an early work commitment, Raugust says he opted to stay closer to town, and crashed at nearby Rick Scarborough’s, where he’d stayed occasionally in recent weeks.

Raugust says Scarborough was awake when he arrived and, when he awoke that morning at dawn, that Scarborough was in the shower. Raugust asked him for a ride to the job site and witnesses say he arrived to work at 6:17 a.m., 51 minutes after Ross called 9-1-1 to report the shooting.

Randy Fisher has also provided a sworn affidavit saying Ross confessed on two separate occasions to killing Tash, including during an encounter in which Ross threatened him at knifepoint; in an effort to lend credibility to the threat, Ross alluded to killing Tash, pressing the blade against Fisher and accusing him of being a snitch.

Ross has since refused to answer questions about the Tash murder, and at the evidentiary hearing invoked his rights under the Fifth Amendment to the United States Constitution.

Zimmerman, the county attorney opposing Raugust’s efforts for a new trial, says Fisher’s testimony carries no weight, and that even if it did shed light on new evidence Ross is an alcoholic and is not credible.

“Even if it were new evidence, the mumblings of a drunk town drunk has absolutely no reliability,” Zimmerman wrote in his brief of opposition.

But Brett Schandelson, an attorney working on the case for the Montana Innocence Project, says the state cannot characterize its own witnesses as lacking credibility now after previously presenting them as credible at the time of Raugust’s murder trial.

In the case of Ross, Schandelson says, the state presented him as a star witness, and now wishes to discredit him.

He wrote in his petition for relief: “Simply put, the State is on one hand asking this court to ignore the plethora of evidence that, at a minimum, casts significant doubt about [Raugust’s] conviction – if not outright shows [Raugust] is innocent – because the State’s highly credible star witness, Ross, testified that [Raugust] killed Tash. On the other hand, however, the State is asking this Court to ignore Ross’ repeated confessions and refusal to answer any questions regarding his involvement in the Tash murder, because Ross is not credible. Apparently the State had no issues with Ross’ credibility when it called Ross to testify against [Raugust] at trial, argued to the jury that Ross should be believed, and now continues to defend [Raugust’s] conviction based on Ross’ testimony. The state cannot have it both ways – either Ross lacks credibility and his trial testimony is similarly worthy of significant distrust (a position supported by the entirety of evidence presented to this Court), or Ross is credible and his repeated confessions must be given weight. Either way supports [Raugust’s] innocence.”

Zimmerman also says Deputy Abbey’s testimony lacks credibility, that it’s a departure from his previous account of seeing the vehicles, and that at the time of Raugust’s trial he had been disciplined by a previous law enforcement agency in Billings, resulting in his firing. Not only does his testimony at the Raugust trial differ from his testimony at the evidentiary hearing last year, Zimmerman said, but his frustrations with the Billings Police Department gives him a motive to “exact revenge” on other law enforcement agencies, the prosecutor argued.

“This Court should, in light of all of the evidence introduced at the trial, find that Abbey lacks credibility. Abbey’s firing by the City of Billings provides a motive for him to testify falsely at the hearing on this matter. That is, to exact revenge against law enforcement agencies,” Zimmerman wrote. “Had he seen someone get out of the vehicle the evidence could perhaps be characterized as critical. As it stands now the new evidence leads to speculation at best and nothing else.”

Again, Schandelson accuses the state of “trying to have it both ways,” presenting Abbey as credible at trial – which occurred after his firing from the Billings agency – and incredible in Raugust’s post-trial proceedings.

The group has also obtained an expert witness who disputes the accuracy of “ear-witness” testimony from Tash’s neighbors placing Raugust at the crime scene.

The ear-witness testimony came from a family who lived in a neighboring trailer to Tash’s, and who testified that they heard the voices of Raugust, Tash and Ross at the crime scene, “whooping and hollering into the night.”

Dan Yarmey, an expert in ear-witness identification, reviewed evidence from the Montana Innocence Project and urged the court to view the family’s testimony that they heard Raugust’s voice among a group of people with “extreme caution” because ear-witness testimony is often inaccurate.

The defense team also asserts that several witnesses establish a connection between Scarborough and Ross on the morning of the murder, including Lori and Doug Cooper, Scarborough’s neighbors who saw Ross’ AMC Eagle pull up to Scarborough’s house with its headlights off between 5 a.m. and 5:15 a.m. – before the 9-1-1 call to report the murder.

Doug Cooper, a volunteer firefighter, says he recalls his wife commenting, “Isn’t it stupid that Rory Ross doesn’t have his headlights on,” he said, and a short while later, at 5:42 a.m., he received a page to respond to a fire in the Swamp Creek area.

“The reason I can recall the incidents of that morning in such detail is because it was the same day that we learned of a murder in the Swamp Creek area. Seeing a car without headlights, receiving a fire page and then learning of a murder at the scene of the fire seemed bizarre. The events of that morning have stayed with me ever since,” Cooper stated in an affidavit.

One of Raugust’s strongest supporters has become something of a wallflower in the case, but the behind-the-scenes legwork of Mary Webster, Raugust’s sister, helped get the ball rolling in a case the inmate was otherwise helpless to pursue.

“I was his legs and his means to accomplish these goals,” Webster, an attorney in California, said. “I’ve never had a doubt in my mind that Richard is innocent, and the thing that’s really struck me is that everyone touched by this case believes in his innocence.”

Those people touched by the case includes Tudy Cox, the court recorder at Raugust’s trial, who attended last year’s evidentiary hearing in a sign of support for Raugust.

Ken Bonner, the ranch hand with whom Raugust met Tash more than 30 years ago, remembers when a detective called him 18 years ago to tell him about Tash’s death and Raugust’s arrest.

“I told him, ‘You’ve got the wrong man,’” he said in a recent phone interview from his home in Mount Shasta. “I know the boys, I’ve known them their whole lives and there is no way that Richard killed Joe. He couldn’t kill Joe, there is no way. I still can’t believe this, it just gets me so mad.”

Raugust gave up being mad a long time ago, leveling out his thoughts on injustice by writing poetry and trying to publish a book, “Fishers of Trout and Men,” an artistic effort to reach veterans and curb suicide rates through tales of trout fishing.

And while his indignation has ebbed, his faith in his innocence and his resolve to be free has not, telling a departing stranger, “I’ll see you on the streams.”

“The evidence is overwhelming. I’ve had a 12th-grade education and some self-learning, but even an eighth-grader can figure this out,” Raugust said. “I’m hopeful.”