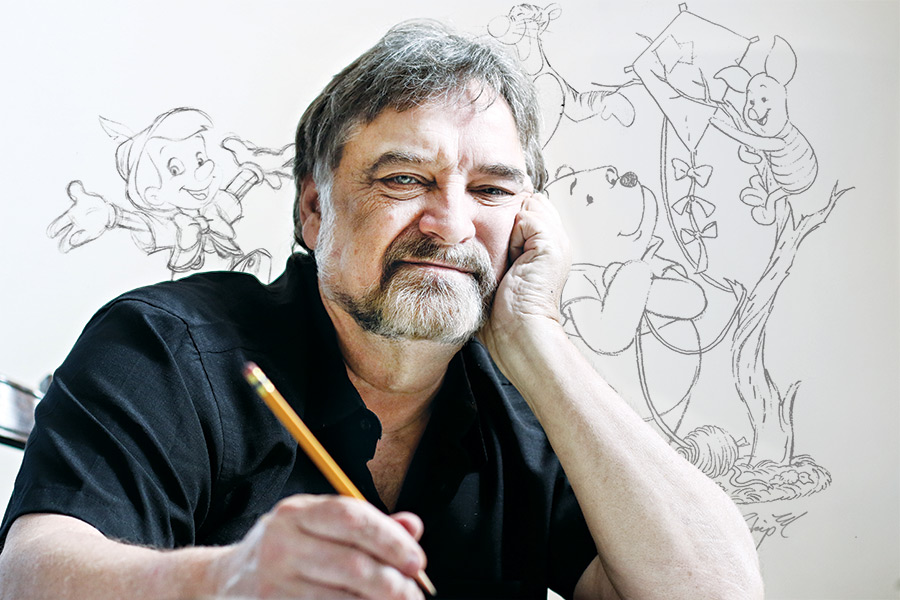

Skip Morgan pulls the legal pad toward him and begins to sketch. Below his careful hands, the familiar faces of Mickey Mouse and Goofy take shape. The pencil moves without hesitation. These are lines Skip has drawn thousands of times before.

He knows, precisely, where to place Mickey’s ears and how to rest Goofy’s jaunty hat. How big to make their eyes, and how to focus them. The exact curvature of the open-mouthed, toothy smiles.

Minutes later, there they are: Mickey and Goofy.

He marks the paper with a practiced signature and the date: Aug. 3, 2015. This time, they won’t be seen by audiences across the planet. This time, he’s brought Mickey and Goofy to life in his quiet Kalispell home.

“I did these,” says the 64-year old, looking at the faces on yellow-lined paper, “to see if I can still draw.”

He can. Of course, he can.

In 2007, Skip ended a 23-year Disney career as an artist protecting the integrity of these characters. Though he draws less since moving to Montana, the characters haven’t left him. They never will.

In 1980, a 29-year old Skip moved from his native Kansas to Los Angeles. The Midwesterner had recently divorced and there was no local work for cartoonists. So he left, westward bound with $200, a fine arts degree from the University of Kansas, and his drawing portfolio. He made his new home in a toolshed, which cost him $50 per month in rent.

After spending a few years at various production companies, The Walt Disney Studios began to take notice of his work. As the company embarked on its first productions of animated television shows in 1984, it offered him a job. By 1985, Skip had worked his way up to the top of the art department.

“When [Skip] was hired at Disney, he put every ounce of motivation and talent into his work because he believed in the morals that Walt had instilled in the company,” Skip’s daughter, Amber Howell, who still lives in Kansas, said. “Primarily, that the art is what is most important, and there should be no shortcuts when putting out the very best of Disney art for the world to see.”

As Associate Art Director, Skip oversaw the artwork and visual imagery for five Disney TV cartoons, including DuckTails, which won Daytime Emmys for Outstanding Animated Programming. Every image that aired on those shows required Skip’s stamp of approval.

After writers sent Skip the week’s script and stick figure storyboard, he decided how to visually render each scene’s dialogue and drama. He also created the “incidental cast,” the episode’s background characters, and drew up reference sheets that depicted each new character from multiple angles so his staff could accurately reproduce them. Then, he and his artists would start drawing.

As Skip saw it, his characters were “like actors in a movie. Alive. They interact; they have emotions. They have limitations.”

For the right spirit – the indefinable Mickey-ness or Scrooge McDuck-ness – to translate on screen, Skip had to bring the characters alive within himself. He speaks of them like old friends. He’s proud of their strengths, concedes their weaknesses, and, ultimately, is certain of their essential goodness.

“The fact that [Skip] drew [the characters] so well shows his emotional attachment to them,” said Willy Ito, the now-retired Director of Character Art International in Disney’s consumer products department. Ito first began working for the company in 1954, when Walt Disney was still alive.

Giving the characters life also meant that their forms had to be drawn right, every single time, 24 times per second of television. Viewers would recognize any mistakes immediately. Rather than as a professional embarrassment, Skip viewed flaws in the art as a betrayal to the characters.

Skip’s artists were skilled. The difficulty was meeting the emotional expectations of a large audience that held Walt’s characters dear. “Mickey speaks to the world,” Skip said, “and he belongs to everyone.” The characters had widespread appeal, and Skip had to do their personalities justice in each depiction.

“Mickey is the perfect guy. Every guy would like to be looked upon with the admiration people have for Mickey,” Skip continued. “He tries to do the right thing all the time, even though he has all the failings and emotions that humans have … and [though] they have their problems, he and Minnie are a perfect couple.”

As Skip’s daughter said, “Who doesn’t love Mickey Mouse?”

Nearly everyone has a special relationship with Mickey and other Disney characters, and few people understand that better than Skip.

But that meant coworkers came to him with his or her own ideas of what Disney’s characters should look like. In the company’s higher-ups, that translated into requests for images Skip believed were disloyal to Walt’s original work.

“The thing about Walt Disney was that he thought of things that had not been done. He created new ideas,” Skip said. Therefore, trying to improve upon or change Walt’s work was inconceivable. To Skip, the classic Disney brand is no longer classic Disney if it has been altered.

“One guy [in discussions about the logo] said, ‘Let’s cut that character crap and do a big D.’ Like a Gucci D!” Skip said. “No, that’s not what America wants. They want Mickey.”

Once created, Walt’s characters were alive. Skip got to know them so well that they existed, truly, in his mind and on the paper before him. And certain changes became incompatible with reality.

“I can’t believe people had the audacity,” Skip said. “There was nobody like him or ever will be again. It’s dangerous to try to improve on a classic… I was protective [of Walt] to the point where I was called a hothead.”

Skip remembers a pitch to reinvent Noah’s Arc with Winnie the Pooh characters. Pooh would play Noah, Piglet would be his wife, and they’d bring aboard the Arc two Eyores, two Tiggers, and so on.

“I stood up in the meeting and said, ‘Hold it, buddy!’” Skip said. “That enraged me.”

Skip explained that Walt wouldn’t make a religious epic, Piglet is male, and besides, how many times has Tigger said he’s the only one?

“He never let anyone forget that [Disney] all started with one determined, talented man,” Howell said. “When I was young and we would go to Disneyland, he would point out the light in the window above the fire station on Main Street and say, ‘That was Walt’s apartment.’”

Indeed, Disney Studios never produced Pooh’s Arc, and the responsibility of safeguarding Walt’s legacy was a welcome one.

“I couldn’t be luckier to have this talent,” Skip said. “This had been my dream ever since I was a little kid. I did what I loved.”

He got paid to draw, paid to create. It was his job to nourish Disney’s characters, all while working alongside other artists who held the same reverence for Walt and excitement about the craft.

Every day was an adventure. While working on his television shows, he’d often be interrupted with the request for an entirely new cast of characters for an undeveloped cartoon about lizards or elephants or aardvarks or dinosaurs.

“I love dinos!” he’d exclaim, and start scribbling.

Occasionally, when talking about his goofiest work, he’ll give a dismissive snort. Still, the amused dignity in his voice betrays his belief in the characters that Walt’s creative genius produced. Even if – especially if – we don’t fully understand it. At the end of the day, there is a pride in that, in fulfilling the duty of keeping the great Walt Disney’s genius alive and well.

By 1990, when Skip was almost 40, the workload of overseeing the artistic production of five cartoons while concurrently creating hundreds of new characters and developing new programs caught up with him.

“My head was about to explode,” he said. “I was working day and night.”

So after five years, he stepped down. He didn’t want to leave Disney, so he answered Willie Ito’s call for character artists in the consumer productions department, which manages companies like Applause that license imagery to make and sell souvenirs.

“He’s very, very talented,” said Ito. “We were fortunate to have him come over and join us.”

In 1992, Skip became the director for consumer products. His job was to make sure the products that licensees wanted to sell didn’t “compromise [the characters’] character or personalities…I had to make sure they’d do it the way Walt would have approved of because he’s a god,” Skip said. He did this for 15 years, the majority of his career with Disney. The work satisfied him – he says he found just as much creative freedom as he did back in the art department.

“I feel that a lot of the stuff we did is still out there. People hand it down generation to generation… that makes me feel good,” Skip says. He recently saw a couple wearing T-shirts he designed in the ‘90s; it was the set where the woman’s shirt features a picture of Minnie, and the men’s a matching one of Mickey.

Finally, in 2007, he retired, grateful for his career and ready to claim his benefits. He stayed in Los Angeles for a few years, close to friends and his girlfriend of 10 years.

In 2014, he traveled to Glacier National Park. He stayed the night in Browning, and the next morning drove across the Going-to-the-Sun-Road. The park was foggy, and he couldn’t see much. Then the clouds cleared.

“I saw this beautiful country and there was something about it,” he said, expressing a first reaction shared by many who move to the valley. “I just started thinking, ‘I love this place.’”

He began driving around the towns in the valley, looking at the log cabins, which he had liked since childhood. The buildings from cowboy eras past reminded him of his hometown of El Dorado, Kansas.

In a Bigfork neighborhood, he came upon a fawn, which was standing by the side of the road.

“It was a Bambi,” Skip said, “[It was] saying, ‘What are you waiting for?’”

When he returned to California, he began calling real estate agents in Kalispell. Within a year, he had sold his home, convinced his girlfriend to move with him, and settled down into a modest home overlooking the valley.

Skip brought all his art tools with him and he has started exploring the artistic community here, excited about the prospects of the artsy edge at local farmers markets. He loves fishing, and though he shoots arrows, he prefers to aim at targets. Who knows what familiar creatures might be hidden in the woods?

His new home hardly hints at the fact that its new owner spent a career creating Disney merchandise. It’s the log cabin he always wanted. There is one golden frame in the dining room, though, that sticks out. It holds a portrait of Scrooge McDuck, striking a distinguished pose that captures the perfect, indefinable, Scrooge-ness.