There is a crisis at the Kalispell child protection services office, with a high turnover rate of employees leaving little consistency for the children and families already in service, and just three permanent staffers on board to investigate dozens of new child abuse claims each month.

The situation has reached enough of a boiling point to receive attention from local law enforcement and children welfare officials, who in a recent letter pointedly asked the state’s Department of Public Health and Human Services (DPHHS) to rectify the issue because such a vulnerable population is at risk.

The letter comes at a time when the state’s Child and Family Services Division (CFSD) is already under public scrutiny. A group of Montana grandparents protested the Kalispell office on Sept. 8 for more rights, and the state is at risk of losing federal grant funding because its privacy laws don’t allow for standard mandating reports of child abuse deaths.

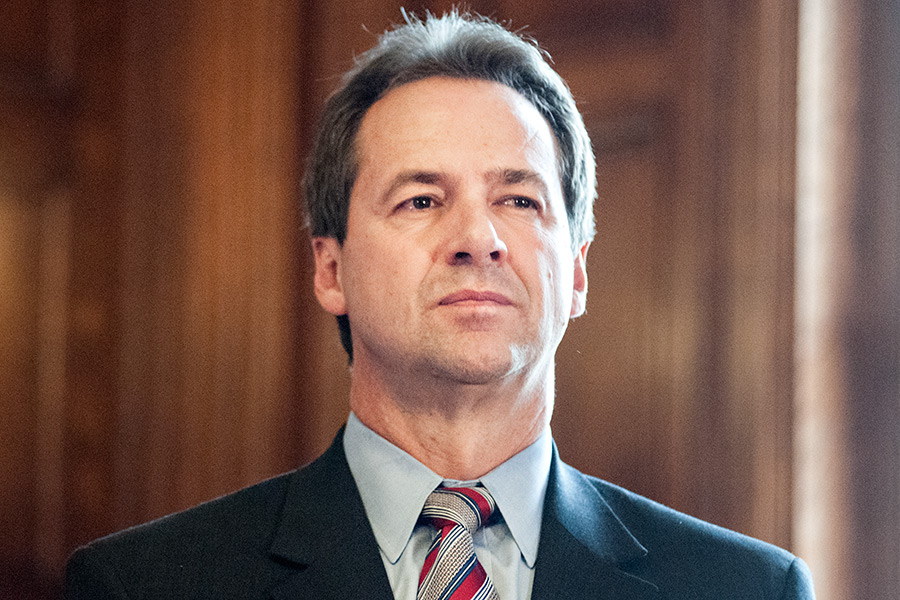

There has been enough of an outcry that Gov. Steve Bullock announced on Sept. 21 a new initiative to protect Montana’s children.

Permanent staffing levels for child protection specialists in Kalispell are at unprecedented lows, and the state has resorted to bringing in temporary workers and retired supervisors to cover the gaps left in care.

So far this year, 12 of the total 15 positions at the Kalispell CFSD office have turned over. The office is charged with investigating reports of child abuse in Flathead County and following up with necessary cases.

Officials from DPHHS say there are many contributing factors to the lack of staffing, including not being able to find enough qualified professionals to fill the child protection specialist positions.

But former employees of the Kalispell and Lake County offices allege that an unsupportive management culture has pushed many skilled and qualified workers out of their jobs or away from CFSD in general.

While the root of this problem may be up for debate, all parties involved agree that the safety and protection of Montana’s children is and should be the top priority. But while the discussion continues, local children are left in dangerous and vulnerable situations.

Devin Kuntz, program coordinator and forensic interviewer with the Flathead County Children’s Advocacy Center, said that CFSD is a vital resource, and the high turnover rate affects children and families.

“An agency like that, if they’re experiencing turnover, there’s going to be a negative impact or at the very least an impact to the people they serve,” Kuntz said. “Any lag time is bad, especially when it’s cases that involve kids.”

At its core, CFSD works to protect children who “are at substantial risk of abuse, neglect or abandonment,” to ensure children have safe family environments, and to collaborate with community resources in an effort to promote child safety.

CFSD operates a child abuse hotline in Helena, where intake specialists screen calls, assess the risk to children, prioritize reports, and then send those reports to social workers in county offices for investigation.

The division also plays a key role on many interdisciplinary teams in the valley tasked with protecting children, such as the Flathead County Multidisciplinary Team, which consists of local law enforcement agencies, the Flathead County Attorney’s Office, Youth Court Services, the Kalispell Regional Hospital Sexual Assault Nurse Examiner Program, and the Western Montana Mental Health Center – Stillwater Therapeutic Services.

On Sept. 16, the Flathead County Children’s Advocacy Center, on behalf of the multidisciplinary team, sent a letter to Sarah Corbally, the CFSD administrator for DPHHS, regarding the high turnover rate at Kalispell’s child protection office, with concerns about inconsistencies in staffing, lack of participation in important meetings, and the possibility of losing grant money because CFSD isn’t showing up.

The letter says CFSD has not had a representative at the multidisciplinary team’s case review sessions since June, and the division has not responded to forensic interview notifications since August.

“(There was) one emailed response saying resources are not at sufficient levels to participate at this time,” the letter reads. “This is having detrimental effects on case development, coordination, communication, collaboration, and interagency relations with CFSD. Professional working relationships are near impossible to develop and maintain presently. Our primary concern is child safety/protection.”

Without participation from CFSD on the multidisciplinary team, the Children’s Advocacy Center could lose its accreditation with the National Children’s Alliance, which would affect funding and training.

The letter also describes a “public outcry” at the lack of services, including a Sept. 8 protest outside of the CFSD offices.

“Most importantly, the absence of CFSD negatively impacts the effective investigation and prosecution of child abuse which negatively impacts our ability to help families and address child abuse and neglect,” the letter reads.

In a Sept. 18 interview, Corbally said the letter mirrors her division’s concerns about staffing in the Kalispell office, and that only having three permanent workers would make it difficult to cover all the responsibilities at the office.

“We obviously are very concerned about this issue,” Corbally said of the turnover rate.

Her division put together a resiliency committee to help with recruitment and retention, she said, and reinforcements at the Kalispell office include retired supervisors and former long-term staff members who came back, as well as an additional three hires expected soon.

CFSD doesn’t have an exact figure on how much it costs to keep the Kalispell office staffed, but “we know that it is expensive.”

“The reality is, we have to pay because this is a critical service from the state and we can’t afford not to have staff in Kalispell, no matter what it takes,” Corbally said.

Having bodies in the office is one thing, but keeping it permanently staffed is another. Corbally said turnover is a problem throughout her division statewide, often because people move on from the job or because they weren’t prepared for the challenges that come with it.

“I think it is a more complex job than anyone can comprehend,” she said, noting a lengthy list of federal requirements tagged to each case.

Nationally, certain child welfare agencies might see turnover in the 90 percent range, according to the Child Welfare Information Bureau. And Corbally said it’s not uncommon to see turnover in the 40 percent range, as her division has experienced in recent years.

In Kalispell, Corbally said the office isn’t receiving enough attention from qualified applicants.

“We are not even getting qualified applicants in a number that’s sufficient to fill the office,” she said.

However, former workers who were either fired from the division or quit on their own accord said the environment at the Kalispell office is unsupportive, and initiative is tamped down.

For several of the workers interviewed, problems started in 2011 when CFSD switched its operational model to the Safety Assessment and Management System (SAMS).

Corbally said this systemic change was put in place before her tenure as administrator at CFSD began, but the model was being used in all but seven or eight of the state’s 29 offices at the time.

“It was done not at all to move kids more speedily through the system, but to make it more consistent for families moving through the system,” she said.

By keeping a family with just one social worker, they don’t have to keep bringing a new worker up to speed on the case, Corbally said, and it provides for a more consistent system statewide.

For the staff, though, the change was abrupt. Diane Piorek, a former supervisor in Kalispell and CFSD employee for 23 years, said it caused a divide between the workers and the administration.

“How can you work with families if you can’t work as a family in the office, when you can’t feel safe?” Piorek said. “We can’t work somewhere where the value of what we do isn’t respected.”

Piorek said when she began working with child protection services, the system had two units, each consisting of five or six workers. One unit would investigate and the other would develop treatment plans for the family.

Along with bringing in the new SAMS paradigm, Piorek said division administrators changed the two-unit model to a one-person team receiving the report, investigating it, and then implementing the treatment plan.

That social worker would stay with one case the whole way instead of working on it as a team. It was a major change, Piorek said, and it stretched the child protection crew to the limits.

“That systemic change alone was enough to set a lot of workers on their way,” Piorek said.

The procedural changes also seemed to usher in a new culture in the office, Piorek said. Former employees of the Kalispell office said they were discouraged from discussing cases with one another and were told to stay in their offices.

It’s a management prerogative, she said, but it also shut down an important support network for the social workers, who can’t talk about their cases with spouses or friends due to privacy laws.

“We were a family,” she said. “And when we had bad days, we would pull together.”

Once that support disintegrated, Piorek knew it was time to leave. She quit in 2013. She said there was too much change too fast, and it pushed out workers who couldn’t or wouldn’t tolerate the change.

“When I quit, the attitude there was, ‘Go ahead, we don’t want people here who won’t change,’” Piorek said. “They have a whole new crew. For two years, they’ve gone through I don’t know how many workers.”

Nicole Grossberg, the regional administrator for Western Region 5 at CFSD, said the description of the Kalispell office as an isolating place is “inaccurate,” and that staff members often pair up and talk, free flowing based on the needs of the office.

In Lake County, however, former supervisor and child welfare worker for 28 years Ann Gowen said her Polson CFSD office felt a similar chill in 2012 when she was told her office would close down for a while and employees would have to drive to Missoula or Kalispell for work.

Gowen said employees received little support from the division’s higher-ups when the move occurred and were devastated by the changes. Her feelings were particularly hurt when she heard the rumor that she’d retired. Gowen said she would never quit – if the stress of the job were going to get to her, it probably would have been sooner than almost 30 years after starting.

Slowly, other CFSD employees then started leaving their jobs, she said. The Polson office is currently advertising for four open positions.

“The turnover in Lake County has been obscene,” Gowen said. “We started calling it space abductions. ‘Well, the aliens must have gotten her,’ because people were disappearing and it was being done in the same way, in a way that was not only unfair and disrespectful, but damning for us in the community.”

DPHHS officials said the Polson office was never officially closed, but changes were made in 2012 when caseload levels did not justify the staffing levels there, while the Missoula and Kalispell offices needed extra help. Now, the office remains open, and staff have been added to address an increase in caseloads.

Corbally said her office had not received any formal reports from departing employees regarding any of the issues the former employees spoke about, and if there was an investigation into such claims, she wouldn’t be able to discuss it due to privacy laws.

The state has tried to implement better structure when it comes to child protection worker supervision, Corbally said, because employees had complained about not having enough contact with their supervisors.

Grossberg said CFSD always speaks with workers if they’re leaving their employment, and the division is constantly analyzing and reanalyzing the reasons people leave. Disagreements about SAMS or the new systemic model aren’t very relevant anymore, she said, because those models have been in place for four years now, and for most of the staff, they’re the only systems they’ve known.

She also said the resiliency committee met with the staff in Kalispell, and said it is “actually a very collaborative office.”

“The people in (the Kalispell) office are doing everything possible to try to re-staff it and do good work while we’re there,” Grossberg said.

Multiple former CFSD workers interviewed by the Beacon said the lack of child protection specialists in the Flathead presents an extreme danger to the children and families living here.

With only three people working in the office, there is only so much the staff can do, making it difficult to fully investigate all reports of child abuse. There’s also a lack of consistency for the children and families, who could have trouble receiving the attention their cases may need, and then they have to start over each time with a new child protection specialist.

Piorek, who expressed sadness at no longer working for CFSD, said the division and its workers are necessary and can be a force of good in the community when functioning properly.

“My heart breaks when I think that there’s children in this community who need help and they don’t have it,” Piorek said.

Money and management are two reasons given for a breakdown in child welfare services, though James Caringi, an assistant professor at the University of Montana School of Social Work, said the true root of the problem likely runs much deeper.

Caringi completed a survey with social workers regarding their feelings about their jobs after Corbally commissioned the study. The study’s results were available in September 2013.

He said the results were typical of most child welfare systems, with high turnover rates in organizations that might lose 25 percent of the workforce in a year.

“That’s not unusual,” Caringi said.

According to Caringi’s survey of 200 child welfare workers, there was an overall “high satisfaction” with worker supervision, yet “relatively strong dissatisfaction with their pay, fringe benefits, and opportunities for promotion. Respondents who were thinking of looking for a new job indicated especially lower satisfaction with communication.”

The study also measured respondents’ attitudes toward several aspects of the organizational climate.

“The components rated most highly included two [aspects] related to the job itself (importance and challenges of the work) and several related to supervision (trust and support received, emphasis on goals, and efforts to facilitate work). The items rated lowest included work overload, organizational support, conflicting responsibilities, and justice/fairness in decision-making,” the study reads.

Most of the social workers – 70.7 percent – said if they could go back in time, they would still choose to work in this field. However, 75.5 percent said they had thought of leaving the agency during the previous year and were reasonably serious about it.

The larger issues are with the entire system, which Caringi said suffers from a lack of resources, from financial to personnel.

“What I think needs to happen is we need to not only fund for full funding, but we need to fund for beyond that,” Caringi said. “The system needs improvement right up to the federal level.”

The way the child protection system is set up now allows for tragedies to occur, he said, because there are holes and gaps due to its crisis-driven nature. Corbally agreed with Caringi’s assessment, saying the child welfare system needs to be more preventative in nature.

“The federal system is funded with the focus on reacting after a child has already been abused and neglected,” Corbally said.

During his survey work, Caringi said he found many positives as well, such as dedicated workers and administration.

Montana’s relatively small population could offer an opportunity to bring about real change in the system, he said.

“In order to create a system that would protect more children, we have to dedicate more resources as a society,” Caringi said. “That could be Child and Family Services, but they’re limited with what they can do. It has to be all of us.”

At the most recent session, the Legislature increased funding to the CFSD by more than 7 percent, bringing the division total to more than $133 million. This included $3.3 million for additional staff members to handle child abuse and neglect cases.

This, Corbally said, is a good start, but isn’t enough.

“I don’t think it’s enough to solve the amount of child abuse and neglect in this state,” she said. “I also think within the department, we’re trying to make efforts to do some across-the-division collaborations aimed at doing more prevention work.”

Rep. Ron Ehli, R-Hamilton, the chair of the Children, Families, Health, and Human Services Interim Committee and member of the House Appropriations Committee during the 2015 Legislature, took umbrage at the idea that CFSD is under-funded, saying the staffing problem in Kalispell is more likely the result of poor management.

“At some point in time, the administration has got to stop blaming the Legislature and the funding sources,” Ehli said. “I’m on appropriations and I’m going to stand strong that this is not a legislative problem. This is an administrative problem.”

Ehli said the department’s requests for more money to pay for staffing are hard to meet, considering the high number of open job positions the department can’t keep filled.

“This is not a funding problem,” he said. “Your inability to keep staff has got something to do with internal operations, and not the Legislature.”

Corbally disagreed with Ehli’s assessment, noting that her division had to build its own tools to update to the modern age, such as the caseload reporting system, and the average social worker in Montana is carrying two to three times the recommended average caseload.

“When the Child Welfare League says 10 cases and four investigations, you can look at our workers who have 15 cases and 20 investigations,” Corbally said.

There were some bills aimed at CFSD that did gain traction during the session. House Bill 612 created a new pilot program that would use meetings facilitated by a court diversion officer to informally resolve cases prior to filing an abuse and neglect petition. And in 2013, the Legislature created the Office of Child and Family Ombudsman within the Department of Justice to review and investigate complaints of how DPHHS handled child abuse or neglect cases.

Another failed bill from the 2013 session will also come back into play this fall. During the 2013 session, Rep. Carolyn Pease-Lopez, D-Billings, attempted to pass House Bill 75, which would have required DPHHS to undertake accreditation for child and family services and produce an annual report on the accreditation process.

The bill died in the Human Services Committee, but the committee asked the Legislative Audit Committee to conduct a performance audit of the CFSD. That audit should be available before the end of the year.

The Kalispell office should expect to see more workers soon, Corbally said, and Gov. Steve Bullock’s office has been working with CFSD to address child welfare issues.

“We’ve been in close discussions with the governor’s office because this is a priority,” she said.

On Sept. 21, Bullock announced the new Protect Montana Kids Initiative, which will focus on immediate system improvements, system reviews, and statutory recommendations for the 2017 Legislature.

Bullock said the immediate improvements would include increasing the capacity and skills of frontline workers by hiring 33 additional staff, continuous evaluations and improvements of training, and building a new electronic system to improve case management. The initiative will also bolster supervision and oversight of frontline workers by alleviating caseloads for supervisors, thereby freeing them up to prioritize oversight responsibilities, and develop a formalized process for monitoring compliance with statutory and regulatory timelines.

Another immediate improvement will be the use of evidence-based practices to provide statewide consistency in investigation assessments.

“One of our most important obligations is to protect child victims of abuse and neglect. Unfortunately, for decades our child and family services system has been overburdened and under-resourced, compromising the ability of frontline workers to effectively do their jobs,” Bullock said in a prepared statement. “Today, I’m announcing a series of improvements to this system to better serve children and families across Montana. These improvements are an important step as we continue to work to find ways to bolster this system.”

Bullock also announced the creation of the Protect Montana Kids Commission through an executive order. The commission’s purpose will be to make recommendations on aligning the Montana child protection system with national standards and “best practices in the field of child welfare.”

Corbally also said the division is taking steps to improve training and securing funding from the Legislature, as well as making the jobs in Montana more attractive, potentially through mobility options or pay increases.

At the local level, the former child welfare workers said they hope the Child and Family Services Division can pull itself together, because the work they did and could do is such an important aspect of keeping the community safe and healthy.

Piorek, the former supervisor in Kalispell, said she hopes the community doesn’t lose faith in the CFSD, and that the issue will resolve soon.

“My wish is that (CFSD) can find the sweet spot for the sake of the children and the families,” Piorek said. “It’s a community and we all want it to be healthy.”