Through a limited drawing, hunters could have the once-in-a-lifetime opportunity to kill a grizzly bear in Montana during a spring and fall season, according to preliminary regulations drafted by state wildlife managers.

The first details of a potential hunting season for grizzly bears have emerged in the midst of a heated debate over whether the population in and around Yellowstone National Park should be removed from the federal government’s threatened species list.

Officials from Montana Fish, Wildlife and Parks will present the framework of the possible future hunting season at the May 12 meeting with the Montana Fish and Wildlife Commission in Helena. Hunting would still be prohibited in the national park. State wildlife managers anticipate fewer than 10 grizzlies would be killed annually during the season. Public comment will be accepted at the meeting and through June 17.

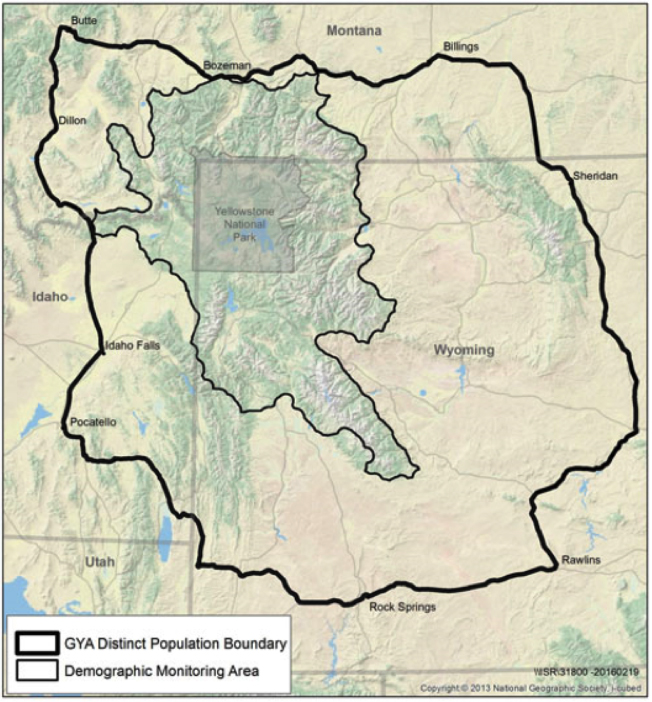

The potential hunting season in a 19,279-square-mile area that includes southwestern Montana hinges on several factors, primarily the animal’s so-called delisting, which the federal government proposed in March. The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service says the Yellowstone region’s bear population — estimated at 717 grizzlies last year — has recovered and no longer meets the definition of an endangered or threatened species under the Endangered Species Act.

As of May 6, four days before the comment deadline, the controversial proposal has attracted national attention and over 3,190 comments. Joining the debate is famed biologist Jane Goodall, who was among 58 scientists to submit a letter this week objecting to the move, saying it is premature and that the overall grizzly population has not recovered throughout its historic range. Also, critics such as David Mattson, a retired wildlife biologist, dispute the population estimates and “junk science” used to support delisting.

The potential hunting season across three states — Montana, Wyoming and Idaho — lies at the center of contention.

Tribal governments have also expressed opposition, citing cultural objections to trophy hunts. The Confederated Salish and Kootenai Tribes are in the process of drafting a letter to submit to the federal government, according to Tom McDonald, fish, wildlife, recreation and conservation director for the CSKT.

“Due to our Tribes’ strong relationship and respect for grizzly bears, it is very safe to say that CSKT has a very high concern about the proposal,” McDonald told the Beacon in an email.

Sportsmen groups have come out in support of the delisting and subsequent season, saying a limited hunt would not have detrimental impacts on the overall population.

“If there are bears that are surplus to our population needs and recovery goals, the public should be able to have an opportunity to hunt some of them,” said Mac Minard, executive director of the Montana Outfitters and Guides Association, which supports the delisting proposal. “Hunting would be a reasonable and responsible use of a sustainable surplus.”

Grizzlies can already be hunted on a limited basis in Alaska, as well as in British Columbia.

»»» Click here to read the state’s draft regulations for a hunting season.

Following the comment period, the federal government will most likely decide whether to remove ESA protections by the end of 2016, according to Chris Servheen, who wrote the delisting rule before retiring last week as the USFWS grizzly bear recovery coordinator. As in the past, Servheen expects there to be a lengthy litigation process as the contentious rule moves through the court system. The agency tried to delist the Yellowstone population in 2007 but a federal court sided with environmentalists who sued, forcing the USFWS to revisit research on the future of whitebark pine, a species whose nuts comprise a critical food source for grizzly bears, and which has dwindled as a result of warming climate conditions.

Depending on the court’s decision in the coming years, the population of grizzlies in the Northern Continental Divide Ecosystem spanning much of Northwest Montana would follow Yellowstone’s path in the coming years. Later this month, the U.S. Forest Service will release its proposed conservation strategy for grizzlies in Northwest Montana.

As part of the federal government’s delisting process, Montana, Wyoming and Idaho are required to outline the structure of a potential hunting season. The season would be based on mortality limits, including road kills, management removals and hunting, in the designated monitoring area in the three-state region known as the Yellowstone ecosystem. The limits would maintain a population of at least 600-747 bears. Any dip below 600 would halt any “discretionary mortalities,” such as hunting.

Quotas for any hunting season would be based on the previous year’s mortality limits and how many bears had died that year, according to John Vore, FWP’s game management bureau chief.

“Specifically for Montana’s draft hunting season structure we were guided by direction in the various documents meant to guide grizzly management,” Vore said. “We brainstormed as to what type of hunting season would best fit. We wanted to be conservative and we wanted to minimize the take of female bears. Montana’s proposed grizzly bear season structure and framework is conservative and designed to minimize take of female bears.”

Under the state’s proposal, there would be seven grizzly bear management units that allowed hunting. Each unit would have its own quota.

A general grizzly license would cost $150 for residents and $1,000 for nonresidents, plus a $50 “trophy license” that would allow for the possession and transport of the trophy. There would also be an $8 conservation fee and $10 base license fee. An individual would be limited to killing one grizzly in their lifetime. Licenses would be issued through a random drawing system. Anyone who drew a grizzly license but did not fill the tag would have to wait seven years before drawing another license. Before being issued a license, a hunter would be required to pass a bear identification test. Hunters would only be allowed to kill adult male and females grizzlies, but it would be illegal to shoot a bear traveling with another bear or bears to avoid killing a female with cubs or a bear two years old or younger. It would also be illegal to use bait or dogs to hunt grizzlies and it would be illegal to take a grizzly while it is in its den.

The proposed spring season would run March 15-April 20 and the fall season would run Nov. 10 through Dec. 15.

According to Vore, the season dates were designed to protect females.

“Females, especially those with young, emerge from dens later in the spring and go in earlier in the fall than do males,” Vore said.

The potential hunting season would be the first in the lower 48 states since the early 1990s. Throughout most of the 20th century, grizzly bears were hunted across Montana. From 1947 to the 1960s, the annual hunting season saw an average of 20 to 60 grizzlies killed, according to government records. Montana residents purchased upwards of 1,700 licenses on an annual basis, although the numbers dropped to roughly 700 after license fees increased in 1971.

The federal government designated the grizzly bear as a threatened species in 1975, but allowed a hunting season to continue in Northwest Montana until 1991, when a federal district judge issued an injunction halting the season. The Fund for Animals and Swan View Coalition sued the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service seeking to end the biannual season, which allowed for up to 14 bears, but no more than six females, to be killed each year. Judge Michael Boudin barred the season on Sept. 27, 1991 and the USFWS went on to revoke its special rule allowing the hunting of grizzlies anywhere in the lower 48.

Twenty-five years later, Keith Hammer, chair of the locally based Swan View Coalition, remains firmly opposed to the delisting and subsequent hunting of grizzlies once again.

“If the agencies were really serious about grizzly bear conservation, they wouldn’t be wanting to take them off the list in the face of increasing human populations and impacts on the ecosystem, whether Yellowstone or up here in the Northern Continental Divide,” he said. “Secondly, they would hold off on even thinking about proposing hunting until they see how the species does under state management if it were delisted.”

Hammer says persistent population growth and development is putting “unrelenting pressure” on grizzlies and their habitat.

“It would be an unmitigated disaster if they delist either the Yellowstone or Northern Continental Divide populations,” he said.

Others disagree, saying the population — estimated at 1,800 across the lower 48 — is robust and ready for state management.

“The proposal to delist grizzlies in the Yellowstone ecosystem is a very important step in an amazing success story,” Vore with FWP said. “We should all be proud of that. The whole idea of the Endangered Species Act is to recover species and get them delisted.”

Correction (May 6): The article previously stated that grizzlies were hunted in Alberta. A moratorium has been placed on the Canadian province’s season.