Preserving America’s Best Idea

A century ago, Stephen Mather embarked on a journey across America to make the case for a unified national park system

By Justin Franz

On a crisp September day in 1915, U.S. District Attorney for Montana Burton K. Wheeler got his car stuck in the mud on a rutted road along the east side of Glacier National Park.

As Wheeler assessed the situation, he noticed a pair of Blackfeet horsemen dragging another vehicle through the muck. As they pulled alongside Wheeler, a man stepped out to lend a hand.

“My name is Stephen Mather,” the man said to Wheeler. “I’m assistant to the secretary of the interior and in charge of the park. Could I be of service?”

“Just the man I’d been waiting to find,” Wheeler shot back, “the one who has the responsibility for this horrible mess passing itself off as a road.”

The mucky situation Assistant Secretary Mather and Wheeler, Montana’s future U.S. senator, found themselves in that early fall day was not unusual in America’s national parks of the era. Although these massive pieces of land were set aside for the enjoyment of all Americans, citizens could rarely take advantage of the parks – and if they did, it wasn’t easy. Roads were rutted, accommodations lacking and information was limited.

To highlight the state of America’s national parks, Mather set out on a yearlong journey to make the case to Congress for a department to oversee and maintain the country’s most treasured lands. The journey took Mather through Montana’s own Glacier National Park.

The idea to protect culturally and naturally significant pieces of land was hatched 500 miles south and 45 years earlier around a campfire in what is today Yellowstone National Park. A Montana lawyer, Cornelius Hedges, was part of an expedition to explore that scenic corner of Montana and Wyoming. While sitting around a campfire in September 1870, Hedges suggested that rather than claim the land for their own profit, the members of the expedition should encourage the government to set aside this special piece of geyser-filled land. Less than two years later, President Ulysses S. Grant signed legislation creating Yellowstone.

By the early 1900s, there was a half-dozen parks scattered across the West, including Sequoia, Yosemite and Mount Rainier. At the time, the parks were under the control of the Department of the Interior and patrolled by armed soldiers. The soldiers were a necessity in what a park service history called “the wild and woolly” West where a few years prior stagecoach robberies were still common. In 1906, Congress approved the Antiquities Act that gave the president authority to create national parks and historic monuments. Within a few years, more parks were established, including Glacier in 1910.

As the number of preserves increased, the need for a “bureau of parks” was apparent, but despite broad support – from President William Howard Taft to influential railroad president Louis W. Hill – the idea languished in Congress.

In 1914, Mather, a Chicago businessman who made millions in the Borax industry, wrote a letter to Secretary of the Interior Franklin Lane railing against the state of the national parks. Mather, who was also a climber and member of the Sierra Club, was enraged that the federal government was ignoring its duties to protect the parks. According to legend, Lane wrote back, “If you don’t like the way the national parks are run, why don’t you come down to Washington and run them yourself?” Mather took him up on the offer.

In January 1915, Lane hired Mather as his assistant secretary to make the case for a national park service.

“Just get out in the country, size up the park problems, do a broad public relations job, so that you can convince Congress of establishing an independent park service bureau,” Lane said. “Besides that, this is a real opportunity for you to do a great public service.”

After moving to Washington, D.C., where he received an annual salary of $2,750, a small sum for a man who had already made millions, Mather headed west. He spent the next nine months bouncing back and forth between the wilderness of the West and a suite of rooms he leased from the Powhatan Hotel at 18th and Pennsylvania.

In California’s Sequoia National Park, Mather found roads so rutted it was common for passengers to have to bail out and push their vehicles to their final destination. Oregon’s Crater Lake National Park was a stunning landscape that few people saw because local accommodations were nearly non-existent. And in Yellowstone, the roads were so steep and so poorly maintained that lines of cars would get stranded.

Along the way, Mather invited outdoorsmen, businessmen and writers on his western adventures. One night, around a campfire in the Sierras, Mather said: “These valleys and heights of the Sierra Nevada are just one small part of the majesty of America … But unless we can protect the areas currently held with a separate government agency we may lose them to selfish interest. And we need this bureau to enhance and enlarge our public lands, to preserve infinitely more ‘for the benefit and enjoyment of the people,’ as the Yellowstone act stated. So I ask you writers to go back and spread the messages to your readers. You businessmen to contact your clubs, organizations, and friends interested in the outdoors. Tell them to help financially and use their influence on members of Congress.”

In September, Mather arrived in Glacie National Park. It did not take him long to start finding problems, specifically the location of park headquarters, near Fish Creek. Mather believed it was unacceptable to have the park’s base of operations at the end of a rutted road so deep into the park. “He stamped his feet and shouted that this situation would never do,” recalled his assistant Horace M. Albright in a book years later. The park superintendent explained that all of the prime real estate near Glacier’s riverside entrance was privately owned, but Mather was unconvinced.

“Well, if that’s the only problem, I’ll buy it myself,” Mather said, as he went off looking for a piece of land suitable for an administrative building. He soon found a plot and paid $8,000 of his own money to secure it for the government.

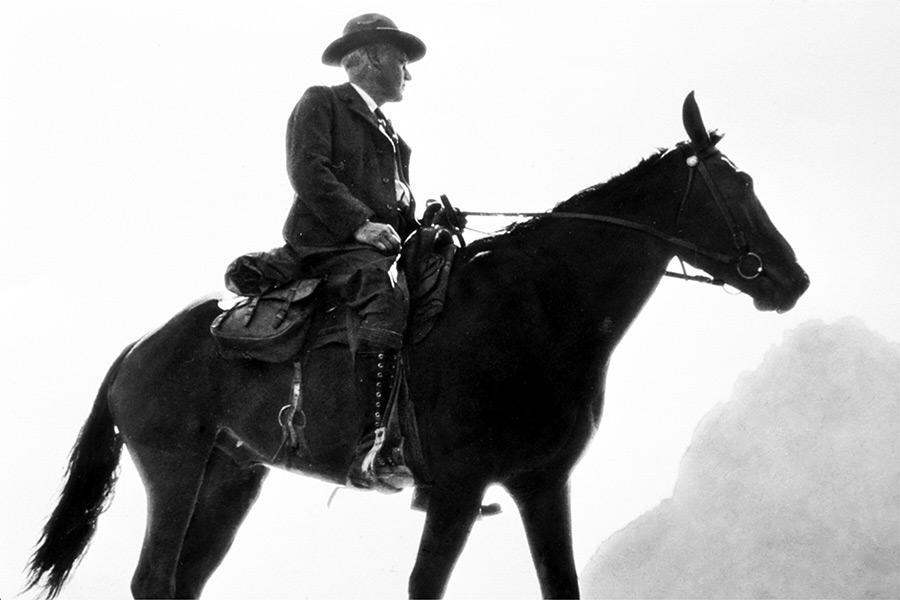

Mather and Albright spent the next few days exploring the park on horseback and staying at the series of chalets built by the Great Northern Railway. Mather was fascinated by the railroad’s luxurious accommodations, especially the massive 155-room Glacier Park Lodge. Soon after the trip, he directed an assistant to get the plans for Glacier’s lodges and chalets and see if similar accommodations could be constructed at other parks.

By November 1915, Mather had traveled more than 35,000 miles touring the nation’s parks. Upon his return to Washington, D.C. he and an assistant came up with a list of why they believed a park service bureau was necessary. At the top of the list was the construction of better roads so that Americans could enjoy the land that was set aside for them. Mather also believed that a park service could create and implement uniformed policies as well as serve as a gatekeeper, ensuring that the land was preserved for future generations.

Mather and his associates worked tirelessly to convince Congress in the summer of 1916 that creating a national park bureau was a worthy cause; no easy task because it was an election year and many of the key players were back home campaigning, Albright recalled later. After a lot of effort, Mather was able to help push the legislation through Congress and to the president’s desk by August. President Woodrow Wilson signed the law creating the National Park Service on Aug. 25, 1916. Mather was dubbed the agency’s first director and the bureau was organized the following year.

As director, Mather stayed involved with the details of running the parks, especially Glacier. In the mid-1920s, Mather played a direct role in the design of Going-to-the-Sun Road. Tasked with drawing up a trans-mountain highway, park engineers had built a direct route over the mountains. But Mather thought it avoided many of the park’s scenic highlights. He believed the road itself should be the destination, not just a way to get from one place to another. He had his engineers redirect the road into the iconic highway it is today.

Perhaps the most legendary tale of Mather in Glacier came from August, 1925. For years, Mather had asked Great Northern Railway officials to take down a sawmill used to construct the Many Glacier Hotel. Mather thought the mill was an eyesore, but the railroad continued to ignore him. Finally, on Aug. 25, 1925, Mather went to Many Glacier and directed a trail crew to line the building with explosives and blow it up in front of hundreds of hotel guests. Mather told guests the show was a birthday gift for his daughter, who turned 19 that day, but Great Northern boss Louis W. Hill was livid.

Mather remained director of the National Park Service until 1929; he died a year later at the age of 62. During his 12 years as director, Mather left an undeniable mark on conservation in the United States. Glacier Park Superintendent Jeff Mow said the system that Mather helped create remains the envy of the world.

“This system is a model for the rest of the world,” Mow said. “Other nations look to the National Park Service for how to protect their own cultural and natural resources.”

Mark Preiss, chief executive officer of the Glacier National Park Conservancy, said Mather also helped start a culture of philanthropy around the parks when he took $8,000 of his own money to buy Glacier a new headquarters.

Today, it is hard not to think of Mather and the role he played in protecting some of America’s greatest landscapes while looking out across the rugged terrain of Glacier Park. It was that same landscape that Mather stared at more than a century ago when he mused about the importance of the job he was given.

“What God-given opportunity has come our way to preserve wonders like these before us?” he said. “We must never forget or abandon our gift.”

This story originally appeared in Glacier Journal. Pick up the inaugural issue, which features four separate commemorative covers, at locations across the valley.