WEST GLACIER – Forty-three years ago, Doug Leen was a park ranger at Grand Teton National Park when a supervisor told him to clean an old barn. Leen was instructed to move everything he found to a burn pile so the barn could be put to better use.

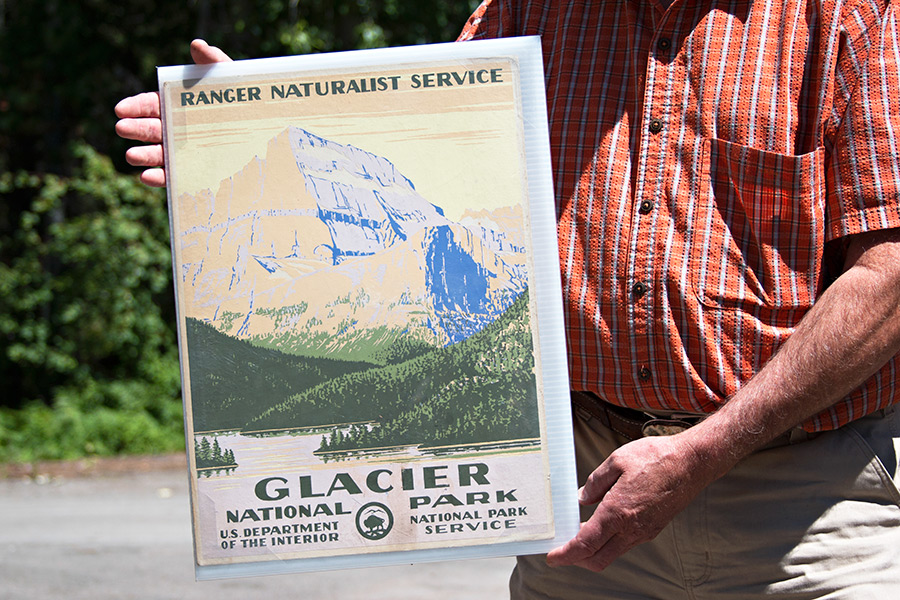

But as he shifted through the barn’s contents an old poster caught his attention. The cardboard placard featured a dramatic screen-print scene of a rocky mountain looming over a pristine lake and encouraged people to “Meet the Ranger Naturalist at Jenny Lake Museum.”

Leen tucked the poster under his arm and took it home to his cabin. A few years later, he brought it with him to his dorm at dentistry school and over time it became an integral piece of every home he lived in. But Leen, who eventually left the park service to work full-time as a dentist in Washington and Alaska, always knew there was something special about his Jenny Lake souvenir.

“Every time I passed that poster, I thought to myself that there was a story that went with it,” Leen said.

Leen was right. The Jenny Lake poster was one of 35,000 different designs produced by the Works Progress Administration between 1935 and 1943. The WPA was created as part of President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s New Deal meant to put Americans back to work during the Great Depression. As part of the New Deal, thousands of writers, musicians, actors and artists were hired to make public art. Among them were artists tasked with creating posters to promote travel, education and safety.

In 1938, the WPA began to produce a series of posters celebrating the National Park System. The first one was for Grand Teton, followed by Yellowstone. Eventually, 14 park posters were created and about 100 of each sent to communities around the parks to promote tourism. The approximately 1,400 Park Service posters were just a fraction of the more than 2 million posters produced by the Federal Art Project in the late 1930s and early 1940s.

With the onset of World War II, people hired to make art were retrained to help in the war effort and the poster program came to an end. After the war, few were interested in saving the posters and, according to Leen, many of the pieces were thrown out or destroyed. Of the 35,000 different posters crafted by WPA artists, 33,000 of the designs are gone.

“Ninety-nine percent of our public poster art was lost forever,” Leen said. “At the time, these posters weren’t considered antique art yet. They were just another old poster.”

To Leen, his wasn’t “just another old poster” and in the years since he made it a personal mission to learn more about it. That search led him the National Park Service’s archives in Harper’s Ferry, West Virginia, where he found black-and-white negatives from 13 other park posters.

In the early 1990s, Leen was talking to a friend from Grand Teton who mentioned the park was looking for something to commemorate the centennial of the Lake Jenny Museum. Leen had the perfect artifact and decided to attempt to reproduce the screen print, despite never dabbling in art before. Soon after, he delivered 600 to the park and they sold like hotcakes. Encouraged by the sales, Leen decided to remake more of the historic posters.

Since then, he’s created a side business, Ranger Doug’s Enterprises, that sells reproduction national park screen prints with the help of graphic designer Brian Maebius.

The screen prints have become so popular that other national parks have commissioned Leen and Maebius to create new posters in the spirit of the WPA originals. Now you can buy posters representing more than two-dozen parks with part of the proceeds from each sale going back into the park system.

Meanwhile, Leen has continued his search for the original posters and today he knows of 42 that survived. Among them are two Glacier Park originals, featuring Swiftcurrent Lake on the east side of the park. He brought one to Glacier last week for a presentation during the park’s monthly brown bag lecture series. He urged park officials to keep looking for more.

“These things have turned up in the park system before,” he said. “They’re flat and they can easily hide.”

So far, Leen has tracked down original posters for every park, except for Wind Cave and Great Smoky Mountains national parks.

This summer, Leen is traveling to parks across the country giving talks about the historic posters and what they mean to the park system. Besides tracking down as many of the original posters as he can, Leen has another goal: make sure every American has a WPA national park poster.

“These are iconic posters,” Leen said. “They certainly don’t belong in a burn pile.”

For more information, visit www.rangerdoug.com.