From Glaciers to Greenhouse Gases, New Technology Emerges

Kalispell native Kendra Kuhl recognized as top innovator in research to convert carbon dioxide into useful products

By Tristan Scott

Growing up in Kalispell offered Kendra Kuhl a unique vantage point to study climate change as she watched the namesake features of nearby Glacier National Park diminished by a warming world.

Her early interest in the natural spaces around her led to a fascination with chemistry, which was further nurtured by general and organic chemistry classes offered at Flathead High School. Her talent in the field provided a springboard into an ambitious academic trajectory, propelling her to the vanguard of scientific research to convert carbon dioxide captured from smokestacks at coal or gas-fired power plants into useful chemicals and products.

“I think being close to Glacier, you see climate change happening firsthand, so it was impactful at an early age,” Kuhl said in a telephone interview with the Beacon. “Also, just growing up in Montana you are so connected to nature. It is the main form of entertainment, and through the years, I watched as less snow remained on the ground during winter. It might seem anecdotal, but growing up there and being immersed in nature was a big influence.”

Kuhl, 34, now resides in Berkeley, California, where she has been working at the Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory to build a reactor that will capture the carbon dioxide emitted by power plants and other industrial processes and make useful chemicals from it.

Kuhl entered the Ph.D. program at Stanford University in 2006 and soon after joined the lab of Prof. Thomas Jaramillo, where her research laid the groundwork for carbon dioxide conversion catalyst discovery by developing new methods for accurate and sensitive quantitation of reaction products, including minor products that had not been previously reported.

After graduating in 2013, she continued her research as a postdoctoral fellow at SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory.

In 2014, Kuhl bonded with Etosha Cave and Nicholas Flanders over a shared interest in reducing greenhouse gas emissions, and the trio teamed up to develop their research on carbon dioxide utilization into an economically viable process.

Together, they cofounded Opus 12, a startup where Kuhl continues working to fine-tune the simple reactor, for which she was recognized last month by MIT Technology Review as one of its “35 Innovators Under 35.”

According to the prestigious Technology Review: “The people in our 16th annual celebration of young innovators are disrupters and dreamers. They’re inquisitive and persistent, inspired and inspiring. No matter whether they’re pursuing medical breakthroughs, refashioning energy technologies, making computers more useful, or engineering cooler electronic devices — and regardless of whether they are heading startups, working in big companies, or doing research in academic labs — they all are poised to be leaders in their fields.”

Opus 12’s technology would enable an artificial carbon cycle that sequesters carbon dioxide in the form of commodity chemicals or creates carbon-neutral fuels, leading to an overall decrease in greenhouse gas emissions.

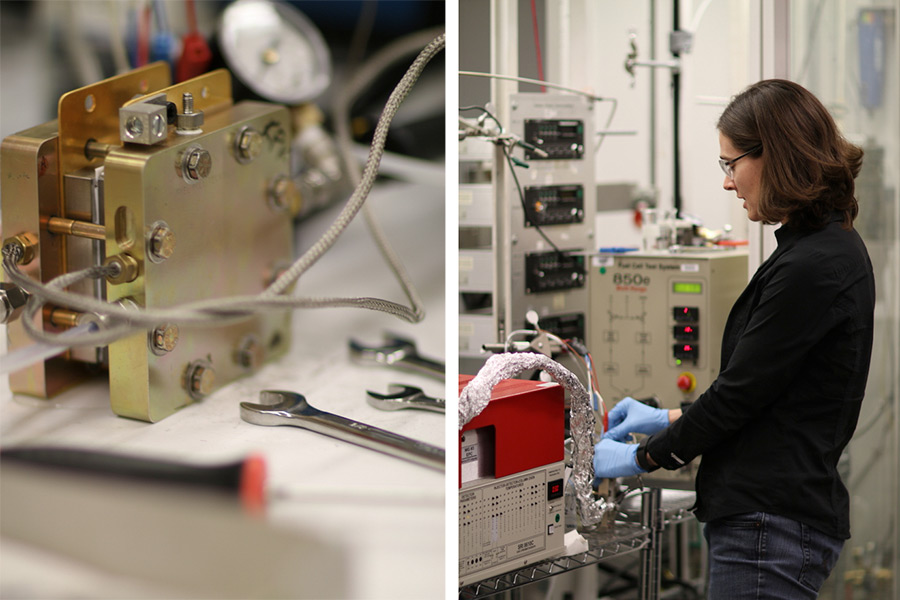

The project was developed through Cyclotron Road, a startup incubator at the Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory, from which Kuhl and the team received funding and salary support to build a small prototype reactor, which features an input for carbon dioxide and an output spigot connected to an instrument that analyzes the products.

With the startup funding set to expire at the end of the year, Kuhl and her team, along with the prototype reactor, have begun to draw private investors who see massive potential in the still-nascent technology.

The key to the technology is the design of the reactor, Kuhl said, which incorporates a family of catalysts she collaborated on with Cave and Flanders during their graduate research at Stanford University. Folded into the metal reactor chamber is an electrode that uses a membrane coated with the catalysts. They enable the carbon reactions to occur at low temperature and pressure, without requiring large amounts of energy.

Opus 12 isn’t the first company to work on converting carbon dioxide into widely used chemicals. But its improved catalysts and scalable reactor design set the company apart, Kuhl said.

“By changing the catalyst, we can change what product is made, so in theory you could make any carbon-containing compound, from everyday household products all the way to commonly used fuels,” she said.

Still, the company has a long journey before it can begin competing with traditional chemical suppliers. By the end of 2017, Opus 12 plans to build a reactor with a stack of electrodes that can produce several kilograms of product a day.

Understanding of carbon dioxide conversion catalysis and reactor design has increased greatly in recent years after a lull in research during the energy crisis of the 1970s, and recent discoveries demonstrate greater product selectivity and higher energy efficiency.

However, these discoveries have yet to enable a commercial process due to difficulties integrating catalysts into a traditional electrolyzer reactor.

Opus 12 incorporates novel electrode materials into an existing electrochemical reactor in order to increase the conversion of carbon dioxide at the catalyst’s surface, which will lead to higher reaction rates that are stable over time.

The Opus 12 team has won the Department of Energy’s Transformational Award as well as multiple grants from the National Science Foundation, NASA, and the Department of Energy. They are alumni of the highly selective Stanford StartX accelerator and the Stanford Venture Studio, and have also received funding from the Shell GameChanger program, the Molecular Foundry at Berkeley Lab and the TomKat Center for Sustainable Energy to further their work toward a commercial device.