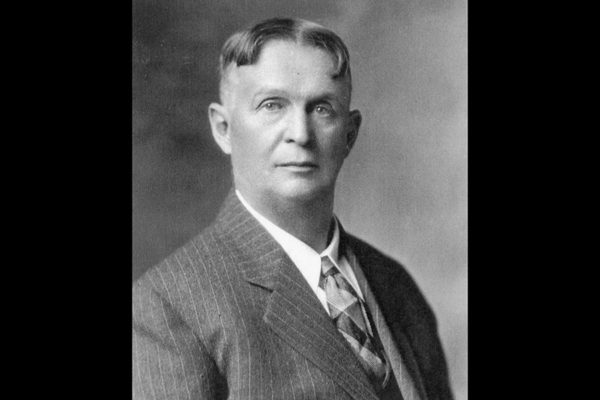

In the summer of 1894, George Snyder, a 23-year-old from Wisconsin, took a gamble by traveling west on the Great Northern Railway in search of riches, like many others of his era did. A few days after his train left Milwaukee, he arrived in Belton, today called West Glacier. He walked a few miles north to the crystal clear waters of Lake McDonald and knew he had struck gold.

“This was a tourism paradise waiting to happen,” wrote author John Fraley in his book Wild River Pioneers, “and (Snyder) would be the one to lead it.”

Even before Glacier National Park was created in 1910, people ventured to Northwest Montana seeking fortunes in the scenic wonders along the Continental Divide. But few mastered that trade as well as Snyder, who built the first hotel on the shores of Lake McDonald, ran a steamship there, and opened a saloon near the park’s entrance, much to the dismay of officials.

Snyder came from a well-to-do family and had the financial backing to make the most of his new home. Because most of the southern end of Lake McDonald had already been claimed, Snyder began to explore the eastern shore, eventually finding a flat spot about a mile below where McDonald Creek enters the lake. In the fall of 1894, Snyder headed down to Kalispell to stake his claim to the land and begin gathering materials for his proposed hotel. He also started looking for a boat.

In early 1895, Snyder purchased a 40-foot-long steamboat and had it moved by rail from Flathead Lake to Belton, where it was loaded onto a wagon and transported to Lake McDonald. Snyder then started constructing a two-story hotel dubbed the Glacier House. The lakeside inn featured a half-dozen rooms, a kitchen and a small dining room.

The Glacier House became a popular spot for visitors who wanted to explore the nearby Sperry Glacier, which Snyder helped discover. The decision to build a hotel proved to be wise as more and more people came to the area, mostly thanks to the encouragement of Great Northern ad men who wanted to sell tickets aboard their trains.

But Snyder wasn’t able to hold on to the property long enough to cash in on the creation of Glacier National Park. In 1906, he lost the Glacier House and the surrounding property, although mystery surrounds exactly how that happened. One version of events is that Snyder was tired of living in such a remote wilderness and sold the hotel. A more intriguing version is that Snyder, who was known to throw a few back from time to time, got drunk during a high-stakes poker game and bet the hotel and lakefront property. According to legend, he lost that hand. Regardless of which story is correct, by spring 1906, the property was in the hands of Olive and John Lewis, who went on to replace the small hotel with the Lake McDonald Lodge, which still stands today.

But Snyder’s time in Glacier wasn’t done yet. A few years later, he opened up a hostel and pub near Glacier’s west entrance, again much to the dismay of park officials. Federal officials took on Snyder and encouraged the county not to give him a license to open the bar. According to Fraley’s book, one of Snyder’s opponents, a competing hotel operator, wrote that the saloon “would be a bad thing to have on the road where all the ladies pass (and) you know that Snyder would be drunk all the time.” Snyder ended up getting his license, but the bar was just the first of many business ventures to annoy park officials. Fraley dubbed Snyder the “Maverick” of Glacier Park.

In later years, federal officials took issue with Snyder’s boat and motorcar tours, but despite numerous lawsuits, they were never able to evict him. It wasn’t until 1923, when Snyder was involved in a drunken, high-speed (8 miles an hour) motorcar crash, that government officials knew they could finally boot the “Maverick.”

Eventually, Snyder moved to Kalispell, out of the crosshairs of Glacier officials. In the 1930s, he suffered a debilitating injury and was sent to the state hospital in Warm Springs. He died in 1944.

Despite being a thorn in park administrators’ sides, Snyder made an undeniable mark on Glacier. Aside from the fact that the patch of land he selected to build a hotel remains a popular park destination 122 years later, there are creeks, lakes and ridges named after him.

“A U.S. Secretary of the Interior, a U.S. Attorney General, a National Park Service Director, six Glacier Park Superintendents, a host of bureaucrats, and an army of government lawyers had tried for years to evict (Snyder) from the Park,” Fraley wrote. “They finally succeeded, but George left a bigger mark on Glacier than all of them combined.”