BIGFORK — Before humping it up forested mountains and swinging a Pulaski, before their baptism by fire, just about every wildland firefighter embarks from a simple beginning like the spark of a flame.

It also starts with a pair of hardy, hard-bottom leather boots.

At 69, Rick Trembath has owned 12 pairs of White’s in his lifetime, and like an old friend, he can remember when and where he was introduced to his first pair.

It was 50 years ago, the summer of 1967. Trembath arrived in the Flathead Valley as a 19-year-old wide-eyed forestry student from Minnesota, hired as a seasonal firefighter for the Flathead National Forest hotshot crew.

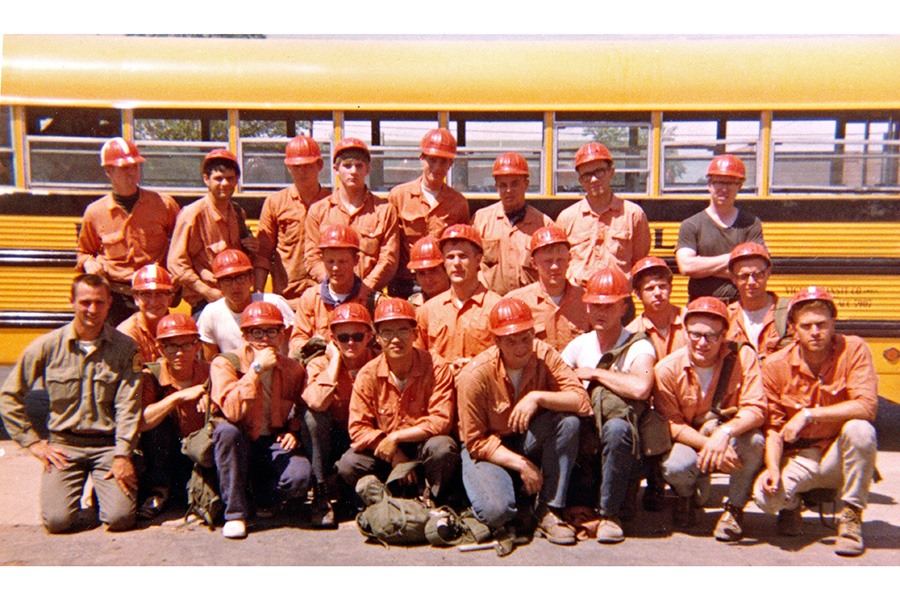

Based out of the U.S. Forest Service’s Big Creek Ranger Station up the North Fork, the hotshot crew was a 25-member group of young men mostly in their late teens or early 20s. The Flathead unit was in its second summer as part of the nation’s nascent Interagency Hotshot Program, which emerged in response to America’s increasing difficulty with widespread firestorms.

The country’s first hotshot teams were rooted in Southern California in the late 1940s as a rugged, multi-skilled unit that got its name for attacking the hottest parts of wildfires with aggressive tactics. In 1962, the Bitterroot and Nez Perce national forests formed the first two interagency teams that could rapidly respond to fires across the country. In 1966, the Nez Perce crew, called the Slate Creek IR Crew, was moved to the Flathead National Forest and became the Big Creek unit.

The original strategy for organizing the hotshot crews was simple: hire forestry students who knew the science of timberlands and athletic young men who could handle the hard work and struggles of fighting fire in the rugged wild.

“It was very physical work,” Trembath recalls. “The idea of these crews was to get into the rougher terrain that equipment couldn’t get into. We would be going into the upper mountainous areas.”

Hence the need for a good pair of boots. But how could a kid from Minnesota know the harsh realities of Montana’s interior? Trembath, one of a few out-of-towners to join the crew, arrived at Big Creek with soft-bottom boots.

“The crew started laughing at me immediately,” he said. “It was a big, huge learning curve that summer.”

Trembath went to Moody’s clothing store in Columbia Falls and picked out that first pair, a set of White’s that ran $49, a hefty price for a young man on his own.

“I still remember, the owner asked me what I was doing, and I told him I was new to fires and working for the government,” Trembath said. “He said, ‘Take the boots and pay me later,’ and wrote a slip and stuck it in the till.”

And so it began. But Trembath and the hotshot crew had no idea what was in store in the summer of ’67.

Fire and smoke are inextricably tied to the landscape, creating an age-old mess for anyone living amongst it. Dating back more than a century, the U.S. has grappled with how to fight fire in the wild, and the debate has only intensified alongside the rising number of destructive and costly incidents.

The rate of large, catastrophic wildfires has increased dramatically in the last decade. Wildfires have consumed millions of acres of forest and destroyed hundreds of homes on an annual basis in recent years, and the number of wildfires bigger than 1,000 acres has doubled across the West since the 1970s. Six of the worst fire seasons in terms of burned acreage have occurred since 2005.

The urgency may seem new, but the struggle is not.

“The concept of forest fires is especially difficult to deal with in an objective manner because fire has deep psychological associations for most animals, especially man,” William Beaufait, a research forester for the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s Northern Forest Fire Laboratory in Missoula, wrote in a seminal 1972 paper describing the nation’s complex relationship with wildfires, which had grown considerably.

Beaufait’s paper focused on the proliferation of large wildfires sweeping the nation in the late 1960s and early ‘70s and the complicated challenges facing the agencies responsible for responding to these dangerous incidents. From the late 19th century to the middle part of the 20th century, the U.S. focused on saving commercial timber supplies and forest communities, particularly in light of the Great Fire of 1910, which chewed up 3 million acres in Montana, Idaho and Washington in only two days.

National fire policy centered on two main strategies: prevent fires and suppress them as soon as possible. This contrasted with the efforts of traditional Native American tribes, as well as ranchers and other settlers who saw the natural benefits of using light burning to improve land conditions.

New resources emerged in the fight against wildfire, including the implementation of aircraft and the creation of smokejumping crews.

The stakes remained high as communities increasingly grew in the forested corners of the West and tragedies emerged, such as the Mann Gulch Fire, where 13 firefighters were killed near Helena in 1949.

American land managers were obsessed with controlling large fires, and their efforts proved relatively successful.

Yet an aftereffect began surfacing, with research, such as Beaufait’s, shedding light on consequences of widespread fire suppression.

“Despite modern technology no reasonable hope exists for isolating accumulated forest fuels from ignition sources,” he wrote.

“Evidence is also accumulating that, by preventing some fires and by suppressing others, man has abetted fuel buildups. Sixty years of protection have predisposed many forests to such conflagrations as the Saddle Mountain and Sleeping Child fires of 1960 and 1961, and the Sundance and Trapper Peak fires of 1967… ”

It was June 1967. A wet spring had swept across western Montana, creating an abundance of grass and brush and dense forests, and early summer had arrived without a speck of precipitation and conditions that dried out the countryside.

A group of seasoned smokejumpers drove up from Missoula to send Trembath and his fellow hotshot crewmembers through a week of training, a rugged exercise that served as their only preparation for a summer of unknowns. The leader was Earl Cooley.

Cooley’s reputation preceded him. On July 12, 1940, Cooley had been one of the first two men to parachute from a plane to fight a forest fire. On Aug. 4, 1949, Cooley was the foreman spotter who chose the location where a group of smokejumpers would land to fight the Mann Gulch Fire. A sudden, unexpected wind shift swept over the group after it landed, killing all but three of the men.

“Earl gave us a lesson on fire behavior and I still remember it,” Trembath said. “That’s why I consider myself a student of fire today. I’ve always been interested in fire because of the 1967 season and that initial training.”

He continued, “Earl was a big rough, rough guy. You wouldn’t want to pick a fight with him. But that day he had tears in his eyes. He told us to learn about fire behavior and understand it because you cannot do the right thing out on the fire unless you know what that fire is going to do.”

As Trembath remembers, Cooley took responsibility for the deaths at the Mann Gulch Fire. Unfortunately, it took a tragedy like Mann Gulch to teach America about the volatile and deadly nature of forest fires.

“After learning that from Earl, we started paying attention,” Trembath said.

Within a few weeks, the 1967 fire season had erupted into one of the worst in American history at that time.

The Flathead hotshot crew was standing atop a peak in northern Idaho when the Sundance Fire blew up, creating a column of dark smoke that climbed into the skies and created spot fires as far away as 10 miles.

“We watched the column from Sundance from 20 miles away,” Trembath said. “It was the biggest column (of smoke) I’d ever seen.”

The Flathead hotshots never stopped that summer, digging line for hours on end in scorching temperatures and rugged terrain. In fact, at one point the crew worked 60 days in a row without a break.

“They wouldn’t let you do that anymore,” Trembath said. “Mentally and physically, you’re just worn out. It was like World War II campaign-type stuff.”

The crew’s equipment was barebones: three radios that often didn’t work, Pulaskis, shovels and helmets. Instead of fire shelters, which were not required until 1977, firefighters followed a simple strategy.

“If it’s looking bad, you don’t stay around. You get the hell out of the way,” Trembath recalled.

On the Cross Mountain Fire, the hotshot crew was preparing for sleep around midnight when Cooley’s warning proved prophetic. The crew had learned about thermal belt ignition, when typical nighttime conditions do not apply and fire behavior can rapidly change.

“It got warmer during the night and caught just the right fuels,” Trembath said. “We were already running like crazy over the saddle of the mountain.”

After some of those types of things,” he added, “you really start paying attention.”

Fortunately, there were no tragedies for the Flathead hotshots during that fateful summer of 1967, although there were significant injuries that Trembath would witness over the next three seasons, including a broken femur. Trembath himself received 10 stitches but saved his hand after a crosscut saw accident during a wildfire in the Lochsa.

In 1969, Trembath’s third and final season as a full-time member of the Flathead hotshots, the crew was scheduled to take a helicopter out of an Alaska fire, but another crew went first. The helicopter crashed, killing one man.

Trembath remembers watching the body bag come into camp. It left an impression on him that remains intact today, and it played a role in his decision to become trained as a safety officer, a certification he still holds today. In 1970, after graduating, he moved to Northwest Montana and joined the Swan Ranger District.

He retired from the Forest Service in 2003 but still holds an active red card, which displays decades of certifications reflecting his acumen in wildland fire. He still responds to fires when needed. He’s traded digging line for another invaluable duty, similar to the way Cooley helped him as a young man. Trembath leads as a fire safety and education specialist, talking with crews and members of the public about the intricacies of wildfire, how it can be dangerous but beneficial on the landscape when handled right. He has seen the nation change how it fights wildfires but still struggle to keep up with severe incidents year after year.

“I don’t think we have a public that has a lot of acceptance of fire,” he said. “They think fire is bad, and it’s not necessarily bad. Fire just is. It’s really something that you need to learn and understand a little bit more of. It needs to be feared at times but it should be embraced as being good for a lot of different things.”

His primary motivator, he said, is to share the lessons he learned from a lifetime on the fireline and help others gain the insight he’s earned the hard way.

“You get your credentials partially through education, but a lot of it is through your performance on the fire line. It’s a practical education,” he said.

“If I can keep some folks out of trouble, that’s worth it.”