Field Notes from a Century on the Shoreline

Morton J. Elrod, one of Montana’s most distinguished naturalists, founded the Flathead Lake Biological Station in 1899 as a testament to the power of intensive fieldwork, and today it is one of the most respected institutions of its kind in the world

By Clare Menzel

Jim Elser walked toward the shoreline at Yellow Bay, a sheltered inlet of Flathead Lake that opens up to miles of teal water to the south. During a pause in the day’s chilly downpour, the sun broke through the clouds, hinting at spring. Elser considered summer. Come June, students from 20 different states and three countries will begin arriving at this secluded property on the lake’s eastern shores to participate in aquatic and terrestrial field ecology courses.

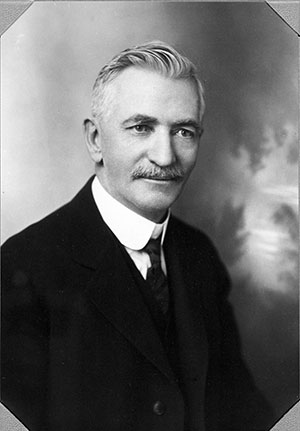

Elser, a renowned freshwater ecologist, is the director of the University of Montana’s ecological research and education center, the Flathead Lake Biological Station, one of the best institutions of its kind in the world. Earlier, Elser had shown a visitor to a small building on the 85-acre campus called the Brick Lab. Built in 1912, it was one of the first structures erected along Yellow Bay. Today, it serves as a museum, housing historical artifacts from the station’s 118 years of operation. Among the items: an umbrella, sunglasses, Glacier National Park’s first guidebook, an elaborate cane, bulky camera equipment. These belonged to Morton John Elrod, a Pennsylvania-born scientist who became UM’s first professor of biology. He was also known for establishing the National Bison Range in Charlo, writing that first guidebook of the national park, serving as its first naturalist, and creating the Nature Guide Service there.

Optimistic and principled to the point of obstinacy, Elrod was a champion of educational fieldwork. He founded the station in 1899 and considered its success his career’s highest priority. He toiled to nurture its development into a respected institution. It became his obsession and his legacy, a love letter and lasting monument to educational field research in Northwest Montana.

Elrod, born April 1863 in Pennsylvania, began teaching as a high school student. He didn’t stop until he was 71, when he suffered a paralytic stroke in June 1934 that robbed him of his ability to speak and write. He worked as a high school teacher and principal in the late 1880s, and then in 1890 became a professor of biology and physics at Illinois Wesleyan University. He taught there until 1896, when he accepted a position at the nascent University of Montana in Missoula, which was founded in 1893.

“Without doubt, the irrepressible allure of the wilderness persuaded him to migrate west,” George Dennison, who served as president of the university from 1990 to 2010, wrote in his biography of Elrod, Montana’s Pioneer Naturalist. “His friends thought it foolish for a man of considerable promise to waste time with this struggling institution in the remote, frontier wilderness of Montana.”

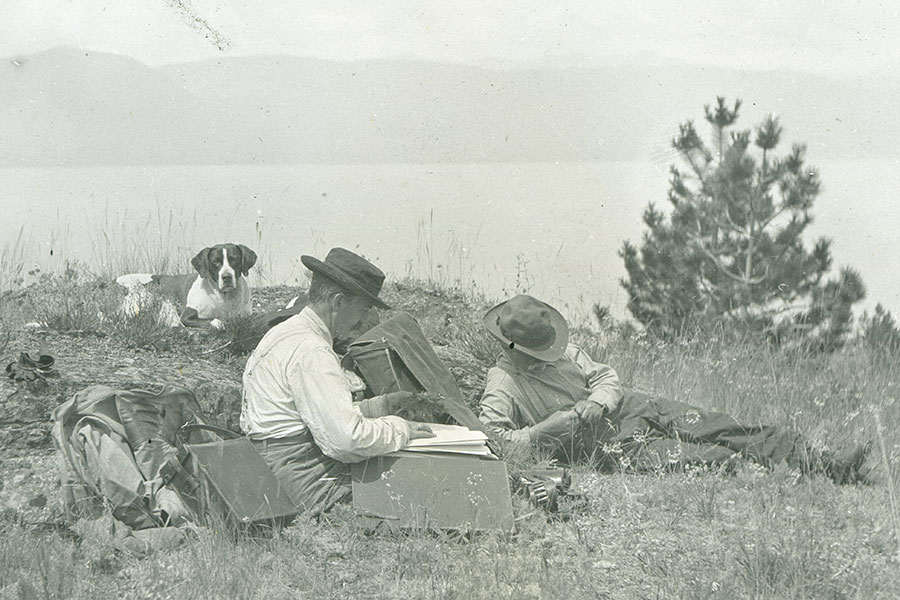

But Elrod, who was then 33, embraced the challenge; in fact, he sought out remoteness. He was humbled by the mighty mountains and became a voracious adventurer, traveling ever deeper into the rugged lands that would become Glacier National Park. Communing with nature, he wrote, is “the richest reward” of such travel. And while, as Dennison wrote, “the wonder of the area at times overwhelmed him,” the naturalist was also driven into wilderness by what he could learn there.

“It is only when one ascends the mountains that the grand panorama is unfolded, and the book of nature is spread out, as it were, where an invitation is extended to all who will read,” Elrod wrote. The mountains and valleys, he believed, were a “scroll on which is written the great story of the past.”

He felt that a student could truly learn only by doing; class study necessarily had to be supplemented with work in the laboratory or field. As he explained in a 1903 Department of Biology report, every student must “get the information first hand and … learn to use all of the senses and correlate the information gained.”

His “dedication to such a unique pedagogical approach deserved a great deal of credit,” Dennison wrote. While active learning is embraced in modern times, it wasn’t popular in Elrod’s era.

Elrod often clashed with his peers and superiors at the university. Dennison describes him as obdurate, insubordinate, dismissive, and self-righteous. Elrod characterized himself as “utterly honest and reliable, possessed of no little talent, willing to work hard for the attainment of valued goals, and committed to the best interests of the university, Missoula and Montana.” He was unwilling to compromise on principle and, as Dennison wrote, “relentlessly critical of and impatient with the university’s labored growth.” He chafed at the leadership of the university’s first president, Oscar John Craig. He became frustrated by the university’s limited resources and the number of students Craig admitted to the institution who were, in Elrod’s opinion, academically inferior.

Though his standards were perhaps unreasonably high, they made him a good teacher. He did not coddle his students. “He never spoon-fed anybody,” Jessie Bierman, a student of Elrod’s who went on to work at the bio station before becoming a leader in child health, said in a 1986 interview. She called him a “marvelous man” and “wonderful teacher.” Professor Charles Adams, a peer at the University of Chicago, described Elrod as a “great teacher” and “man of integrity.”

Those hardened principles made him tenacious. The biology station was established in 1899, just years after he began working in Montana. It launched with little financial support from the university and only bare essentials at a temporary site on the Swan River near Bigfork.

“The object sought in establishing the station,” Elrod wrote, “was to provide a place where some investigations could be carried on, where kindred spirits might meet to work out plans and ideas, and where students could be taught to collect and study material as it is in the wild.” He also included among goals for his students “a better appreciation of living things, plant or animal.”

Biological stations had already been established at universities in Michigan, California and Washington, but Elrod considered Montana’s to be the best, due to the intact natural environment. Flathead Lake is, after all, the biggest freshwater lake west of the Mississippi.

During the station’s first session, he and his pupils undertook surveys, sampling biological specimens and characterizing the terrain, ecology and lake. The majority of these research efforts were descriptive, engaged with collecting, identifying and classifying specimens of the plants and animals living near and in Flathead Lake.

In 1908, Elrod produced his initial report on fish and food sources in the lake. In 1916, he published a study identifying nine species of fish. Then in 1921, Elrod and peer Francis Ross completed their most comprehensive study of Flathead Lake fish, identifying 11 more, such as rainbow trout and bluegill sunfish.

During World War I, and afterward as the nation recovered from the conflict, the station “entered a bleak period,” as Dennison wrote. “Worsening economic conditions” required “aggressive leadership to muster the necessary resources.” The administration was, at turns, unwilling and unable to provide enough financial support, in Elrod’s opinion. He sourced a significant percentage of the station’s project funding from the Fish and Game Commission, among other government entities. For years, lack of funds dogged Elrod, hampering his ability to perform research of the caliber he wanted and to produce publications that he believed would convince the university of the station’s value. In a fight to ensure that the bio station met its potential, he worked many summer sessions without compensation. But his zeal alone couldn’t keep the center open, and in 1931 he submitted his last report. The biological station closed its doors. Three years later, Elrod suffered his stroke.

The station would reopen in 1947, and university relations, as well as funding prospects, have improved under the leadership of the five succeeding station directors. Each of them — Gordon Castle, Richard Solberg, John Tibbs, Jack Stanford, and now Elser — furthered Elrod’s vision, making sure to stay true to his pedagogical approach. They have overseen increasingly rigorous scientific work, testing general theories that fit into a broader national and global ecological framework. They cemented the station as a place where kindred spirits — now perhaps as many as Elrod had imagined — gather from across the globe to study nature, in nature.

Like Elrod, Elser has big plans for the center. He credits his predecessor, Stanford, the institution’s longest-serving director, with dramatically increasing the station’s research profile, expanding the facilities, and establishing reliable income sources through federal and philanthropic funding. The station now receives a quarter of its funding through the University of Montana; another quarter from philanthropic giving; and half from external grants from entities such as the National Science Foundation, U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, and Montana Fish, Wildlife, and Parks.

While the Jefferson Project at Lake George in Upstate New York claims the title of the “world’s smartest lake,” Elser hopes to build the smartest watershed in the world here in Montana.

“We want to know not just what’s going on in the lake in a very intensive way; we’d like to know what’s going on everywhere upstream,” he said. “We’d like to have a more extended sensor network system that’ll tell us about the chemical, physical and biological properties.”

The station now maintains four permanent faculty positions, including Cody Youngbull, a research professor and technologist who is developing a host of sensors and drones to measure lake activity.

“Scientists here, it’s a common phrase for them to say, ‘If only I could measure this; if only I could see this,’” Youngbull said. “By us building sensor space here, now the answer is, ‘Yes, we can build it and answer those questions.’”

The most technologically advanced tools Elrod worked with included binoculars and cameras, but he’d still recognize the science conducted at the biological station, and the philosophy driving it. Students don’t sit in front of PowerPoints, nor have their days ever been filled with lectures. They’re out there on the same lake, on the same river, and in the same mountains as Elrod was. What they’re finding is new, but their reasons for searching haven’t changed from a century ago.

Read more of our best long-form journalism in Flathead Living. Pick up the summer edition for free on newsstands across the valley. Or check it out online at flatheadliving.com.