Lessons From Night of the Grizzlies

The unthinkable tragedy that unfolded 50 years ago in Glacier National Park claimed the lives of two young women and at least five grizzly bears. It also dramatically reshaped the nation’s policies on wildlife and grizzly management.

By Tristan Scott and Justin Franz

Late on the night of Aug. 12, 1967, seasonal ranger Leonard Landa settled into bed after another long day working in Glacier National Park. A schoolteacher in Columbia Falls, Landa was in the midst of his third summer season in Glacier, stationed at the bustling Lake McDonald Ranger Station.

The summer of 1967 was an unusually busy one in the park. Visitation was rapidly increasing, with more than 900,000 people converging on Glacier the previous year. It was also an incredibly dry summer, and, after a series of lightning storms ripped through the park, raging wildfires depleted resources and cast a chalky pall over the Lake McDonald Valley.

Not long after Landa and his wife retired to bed at the ranger station on the north end of the lake, the emergency radio crackled to life. A panicked 22-year-old ranger-naturalist was on the line, reporting there had been a bear attack at the Granite Park Chalet. Landa had a hard time believing what he was hearing. Bear attacks were rare in Glacier National Park; since its creation in 1910, only 11 people had been reportedly injured by grizzlies in eight separate documented incidents.

No one had ever been killed, according to park records.

As a smoky half-moon hung over Lake McDonald, Landa and his wife listened to the drama unfold at Granite Park, tracking the sequence of unprecedented events occurring a dozen miles north of their cabin, culminating in a tragic ending. They eventually succumbed to exhaustion and fell asleep.

Early the next morning, Landa awoke to the frantic sound of people rapping on his cabin door. A group of four park lodge employees in their late teens and early 20s burst through the entrance. They were yelling over one another in chaos, and after a few moments, Landa stopped them, seeking order. He pointed to a young man, instructing him to explain what happened. The boy said a bear at Trout Lake had harassed their hiking party the night before, eventually attacking a girl and dragging her off.

Incredulous, Landa said they were mistaken, that the attack had occurred at Granite Park. The four young people persisted — no, they said, their friend at Trout Lake had been dragged away by a bear.

“I quickly pieced together that we were talking about a second incident,” Landa said in a recent interview.

The unthinkable had happened.

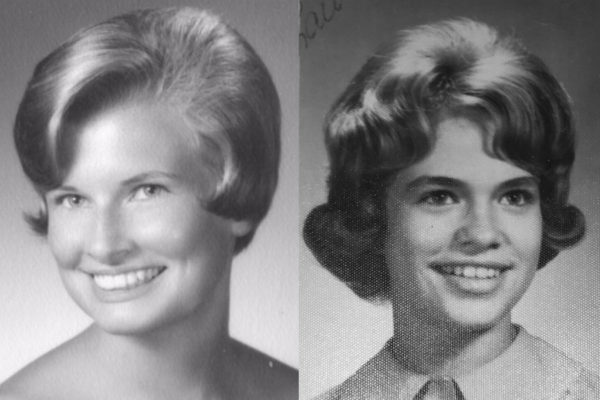

Two young women, at campsites nine miles apart from one another, situated on opposite sides of 9,000-foot Heavens Peak, had been mauled and killed by different grizzly bears on the same night. They were the first bear-related fatalities in park history.

The tragedy, indelibly etched into history as the “Night of the Grizzlies,” would forever change the lives of those involved, and it would transform the nation’s bear management policies.

Granite Park Chalet

Twenty-two-year-old ranger-naturalist Joan Devereaux was barely out of college at Ohio State University, where she majored in botany, when she arrived for her seasonal post at the St. Mary Ranger Station on the morning of Aug. 12, a Saturday.

The day prior, a series of dry lightning strikes laid siege to the valley, and fire lookouts reported more than 100 ground strikes and at least 20 new starts. The emergency wildfire response quickly exhausted the park’s roster of male rangers, and while Devereaux hadn’t been scheduled to lead an overnight group hike — her first as an employee — she volunteered as a last-minute replacement for naturalist Fred Goodsell, who was dispatched to help with the fires.

Clad in her signature gray-and-green National Park Service uniform and armed with an encyclopedic knowledge of plants and wildflowers, Devereaux’s charge was to guide an interpretive tour along the Highline Trail and spend the night at Granite Park Chalet. With about two-dozen hikers in tow, the party arrived at their destination in the early afternoon of a hot and hazy day.

Describing the day’s events later, Devereaux recalled: “The whole trip in was one that was quite normal, no incidents, the usual marmots and flowers.”

Shortly after the group arrived at the chalet, 19-year-old Julie Helgeson, a University of Minnesota student working in the East Glacier Lodge laundry for the summer, and Roy Ducat, 18, a busboy at the lodge from Ohio, struck out for Logan Pass.

In black magic marker, they hastily scrawled “Glacier Park Employees Need Ride” on a pillowcase and began hitchhiking from East Glacier, arriving at the pass and the start of the Highline Trail around 3:30 p.m.

Along the stunning 7.6-mile hike to Granite Park, on an exposed bench-cut trail that tracks along the Garden Wall, Helgeson and Ducat encountered another group of chalet-bound hikers eating lunch — Helena residents Riley Johnson, his wife, Roberta, and their 9-month-old son, who was affixed to Riley’s back on a pack board. Also with them were friends Dan and Judy Regan.

“We were sitting having lunch when the boy and the girl came by and stopped and chatted with us,” Riley Johnson said. “They got up and moved along, and I didn’t see either of them again until the incident. But we did get to meet them.”

The scene at the chalet that evening was pleasant as guests basked in the sun and watched the smoke swirl around the fires flanking Lake McDonald Valley. Dinner conversation in the main chalet was punctuated with excited chatter about the summer’s most talked-about spectacle at Granite Park — the dusky arrival of grizzly bears who each night frequented the makeshift garbage dump about 100 yards below the chalet, where concessioner employees deposited ham bones and other dinner scraps to entice the bruins.

The food-habituated bears arrived right on schedule, interrupting a group sing-along of “Row, Row, Row Your Boat,” and the guests poured out of the chalet in droves to watch.

“The chalet concession workers had a habit of separating their garbage in order to attract bears to the area … in a clearing where the bears could easily be seen when they came in to feed. I was kind of shocked by this,” Devereaux told park ranger Riley McClelland in an interview two days later.

The first bear to arrive was a large, dark-colored female grizzly, weighing 250 pounds, and the second was a silvertip sow, about 100 pounds larger than the blackish one.

“These were the only two bears we saw in the evening,” Devereaux said. “It was relayed to me by the young man who works up there that there is a third bear that comes in the morning and about midnight. This is a sow with a pair of cubs, and she is apparently quite bold and not frightened by much of anything.”

The 275-pound sow would arrive on schedule, too, but only after the guests were fast asleep.

By the time Helgeson and Ducat arrived at the chalet around 7 p.m., there were no rooms available inside, so they opted to sleep out al fresco in a primitive campground about one-quarter mile below the chalet.

On their way down the trail to camp, Helgeson and Ducat stopped and visited with a young couple named Robert and Janet Klein. Apprehensive about the bears, the Kleins opted to sleep closer to the chalet beside a trail-crew cabin; if a bear approached, they reasoned, they could climb atop its roof for safety.

Helgeson and Ducat carried on down the trail to the campground, spread their sleeping bags on the ground and watched the sunset before going to sleep.

Sometime after midnight, Helgeson awoke to a bear sniffing at her sleeping bag and whispered to Ducat to “play dead,” but moments later the bear knocked them both from their unzipped sleeping bags and sunk its teeth into Ducat’s right shoulder. He remained still and quiet, and the bear turned on Helgeson, biting her before returning to Ducat and biting his left arm and the backs of his legs. The bear returned to Helgeson a final time and dragged her off by her arm.

The Kleins estimate they went to sleep around 10:30 p.m., but woke up two hours later to the sound of screaming.

“We heard the screaming … and the main words I heard were just, ‘Help me, help me,” Klein told rangers. “Someone was yelling this over and over again.”

He continued: “This screaming went on it seemed for a long time — it was probably about a minute-and-a-half or two minutes — and it seemed to get farther and farther away and die down, and finally it reached a crescendo and went down from there and finally stopped. We didn’t know what to do.”

Sitting bolt upright in their sleeping bags, the Kleins heard rustling minutes later, and Ducat appeared in the dark before them, bleeding and in shock, mumbling, “a bear, a bear.”

Along with Don Gullet, another overnight hiker camped nearby, the Kleins leapt into action, climbing atop the trail crew cabinet with flashlights to alert the guests inside the chalet, while Gullet swaddled the injured Ducat in his sleeping bag.

Yelling toward the chalet, the Kleins flashed their light three times. And three times again. They flashed the emergency signal over and over again.

After what seemed like an eternity, someone called down from the balcony above: “Everything OK?” the guest hollered.

“No,” Robert Klein called back. “Bear.”

According to Devereaux, several guests at the chalet began to assemble a search party. The young naturalist dressed quickly and fetched her emergency radio as the group gathered outside, still not understanding the gravity of the situation.

“We were reluctant to accept there had been a bear attack,” said Riley Johnson, the hiker who earlier encountered Helgeson and Ducat on the Highline Trail. “But something was awry, that’s for sure. The one thing that we impressed upon Joan was that she was the one in the uniform and she needed to use it. Here you have 65 people with all kinds of different emotions and experiences, all different ages, up to 79 and down to my 9-month-old son. All different ranges of talent, different fears and levels of panic. And Joan took charge, and she did a doggone good job. Everyone rallied around Joan.” She would later receive a Distinguished Service Award for her efforts that night, the Interior Department’s highest honor.

With Devereaux taking the lead, a group of 10 or 12 guests began heading down the trail from the chalet toward the campground.

“We got about halfway down when we heard the boy screaming, ‘Bear, bear,’” Johnson said. “And then we knew what we were in.”

The group soon stumbled upon a horrific scene.

“We discovered immediately the young boy laying there,” Devereaux reported. “We were informed then that there might be another person, and he started mumbling and moaning about the girl having been dragged off. I immediately began talking over the radio to the west side and the fire cache over there. After several attempts the word came through and they began to understand what we were talking about, and I radioed in that we had an emergency, that there was some bear damage and it was very critical.”

Supervisory ranger Gary Bunney intercepted the radio call at the park’s main fire cache, situated at headquarters in West Glacier, which was being monitored around the clock due to the fires. On the line was Devereaux, requesting helicopter assistance and medical supplies. Three doctors happened to be staying as guests at the chalet that night, but they needed surgical equipment, she said, as well as a transfusion apparatus and plasma. And Ducat needed immediate medical evacuation from the area.

The impromptu search crew transitioned into rescue mode.

Johnson helped break into the trail crew cabin and unearthed an old bedspring, which the group used as a stretcher to carry Ducat up to the chalet while they waited for the helicopter, splaying him out on a dining room table for medical treatment.

“Dan (Regan) and I guided the team up and brought the boy into the lodge,” Johnson said. “I was holding the lanterns over the table where the boy was for the doctors. They were just trying to stop the bleeding. He was conscious, he was talking, and I was standing there with the two lanterns so the doctors could work on him.”

Meanwhile, the search party reorganized to go look for Helgeson, but when Devereaux received word on the radio that a helicopter was en route, she redirected the crew to build small fires around the perimeter of an impromptu landing pad, delaying the search for the girl.

When the Bell helicopter arrived at 3:15 a.m., the pilot, John Westover, could scarcely see the narrow landing zone through the haze of smoke and glare of the guests’ flashlights on the helicopter’s plastic dome, and Devereaux ran inside to ask if any of the guests had any knowledge about landing helicopters.

A young Air Force veteran who had just returned from the Vietnam War, Jack Dykstra, volunteered that he had experience landing helicopters on aircraft carriers and used a pair of flashlights to expertly beckon Westover to the landing zone, using military signals that Westover recognized.

It marked the first of several emergency landings Westover made on the precipitous landscape that night, and the guests recall his acts of bravery as heroic. After loading Ducat into the helicopter, Westover ferried the injured teen to Kalispell for medical treatment.

Meanwhile, ranger Bunney, armed with a .300 H&H Magnum rifle, remained at Granite Park to determine the fate of the missing girl. He and a group of about six guests departed the chalet for the camping area, carrying a washtub in which they’d made a fire. When they arrived at the campsite, it was strewn with shoes, sleeping bags and other belongings, and a trail of blood led downhill. Continuing down the mountain, they discovered a coin purse, and after another 225 feet the blood trail disappeared.

Fanning out, the group heard a faint noise and located Helgeson another 52 feet downhill, lying on her stomach wearing only her cutoff jean shorts. She had been dragged about 342 feet from the camping site and was critically injured, with deep lacerations on her arms and legs, and a punctured lung.

“It hurts,” she said repeatedly.

After rendering first aid with what supplies they had, members of the group wrapped her in sleeping bags, loaded her on the bedspring and carried her to the chalet.

It was 3:45 a.m., and Bunney radioed Chief Ranger Ruben Hart that Helgeson was alive and needed immediate helicopter assistance. Westover, who had by then returned to park headquarters, agreed to make another emergency flight.

Inside the chalet, a team of doctors tended to Helgeson, while a young priest, Father Tom Connolly, sat at the head of the table consoling her.

“I remember the doctors working feverishly, but two big arteries were cut and he kept saying to the nurse, he said, ‘I don’t know, I don’t know,’” recalls Riley Johnson. “Finally as he was working on several wounds, he just stopped and said, ‘She’s gone.’ And everyone just kind of stood up. You could hear a pin drop in that room of 65 people. Everybody knew what had just happened. How many people in their lifetime witness an actual death, particularly a crisis death like that? Not many. It was a trying event for me and my wife.”

Helgeson was pronounced dead at 4:13 a.m., moments before Westover landed the helicopter a second time.

After sending the guests back to their rooms, Devereaux washed the tables and “made it a point to clear up as much as possible of the evidence … so it wouldn’t be so oppressive in the morning when they woke up.”

She made sure the signal fires were out cold and tried to fall asleep, though sleep never came.

The next morning, a somber mood pervaded the chalet as guests made breakfast, packed up their belongings and prepared to hike out.

“The mood there was quite evident that something had happened — rather a depressed feeling was felt by everyone, even the young children sensed this and most of them had been informed about what had happened,” Devereaux said.

A total of 60 guests hiked out together down four-mile Loop Trail, with Johnson taking up the rear to “sweep,” ensuring no one was left behind.

Before departing, he counted 59 guests. Recounting, he again came up with 59 guests. Knowing there should be 60, he began to panic, but then remembered his son.

“I forgot that my own kid was strapped to my back,” Johnson said. “They called me the backpacking father who couldn’t count.”

After shuttling their cars from Logan Pass and driving away from the park, members of the Granite Park group would soon learn that the tragedy they’d witnessed was only half the story.

Trout Lake

On that same Saturday afternoon, Judy Voris burst through the doors of the Lake McDonald Lodge gift shop with news.

Voris was one of the dozens of college students who worked at the lodge and the surrounding shops in the summer of 1967. Since June, the University of Evansville student had been working the counter at the Camp Store, selling everything from ice cream to souvenirs. It was at the Camp Store where she met Ren Fuglestad, one of the “Jammers” who drove the bright red tour buses around the park. Fuglestad asked Voris on a date, and the seed of a summer romance was planted.

Elated by the development, Voris rushed to the gift shop in the lodge to tell her roommate and one of her closest friends in the park: Michele Koons.

But when Voris ran into the gift shop, Koons wasn’t there. Voris remembered that Koons had gone camping at Trout Lake with four other employees — she had even borrowed Voris’ sweatshirt.

Back then, if lodge employees wanted to embark on an overnight trip, they had to get permission from home. A few days earlier, Koons, a 19-year-old from California, had called her parents and told them she wanted to spend a night at Trout Lake. Located about four miles from Lake McDonald, Trout Lake is surrounded by mountains and requires a strenuous hike over Howe Ridge.

Koons and her four friends — Denise Huckle, a 20-year-old lodge clerk; Paul Dunn, a 16-year-old busboy at the East Glacier Park lodge; Ray Noseck, a 23-year-old gas station attendant at Lake McDonald; and his brother Ron Noseck, a 21-year-old waiter at East Glacier Park — arrived at Trout Lake at about 5 p.m. on Aug. 12. The group set up camp, hung their food in a tree and went fishing. Koons, who didn’t fish, volunteered to stay behind and keep an eye on camp. After a few hours, the four other campers joined Koons and started cooking a dinner of hot dogs and trout. Soon after, Koons saw a grizzly bear.

“Here comes a bear,” she said, gesturing to the brush.

The female bear was no stranger to Trout Lake, with numerous people reporting encounters that summer.

“That bear did not have a lot of fear,” a local ranger said later. “The bear would go into camps, scare people off and then chow down on food that was left.”

As the bear approached, Koons and her friends ran for the lake. The sow rummaged through the campers’ supplies and ripped open a bag of food before retreating to the woods. The group quickly gathered their belongings and set up a new campsite closer to the beach. They discussed hiking back to Lake McDonald or Arrow Lake, where there was a shelter, but they decided to stick it out at Trout Lake because it was getting dark and they had heard the shelter was already full. They built a large campfire on the beach in hopes of keeping the bear at bay. They laid out their sleeping bags around the fire and went to sleep at about 11:30 p.m.

A few hours later, the group awoke to find that the bear had returned. The grizzly grabbed a bag of cookies that had been left out and headed back into the woods. Over the next few hours, the bear would return to the camp multiple times. At about 4:30 a.m., the bruin moved in closer to the five campers, who played dead in hopes that it would just sniff around and then leave. But the grizzly walked up to Paul Dunn and bit his sleeping bag. Dunn jolted up, startling the bear, and then quickly climbed a nearby tree. The bear moved on to the other campers, who heeded Dunn’s warning and ran. Everyone climbed trees except for Koons, who couldn’t get out of her sleeping bag in time. The bear bit her in the arm and began dragging her into the trees.

“Oh God, I’m dead,” Koons screamed as the bear hauled her away from her friends. It was the last time anyone heard from her.

The remaining four campers stayed in the trees for an hour or so. When it was light enough to see, they climbed down, grabbed some gear and sprinted back to Lake McDonald to report the incident and get help for Koons. They burst into the Lake McDonald ranger cabin shortly after 8 a.m. and found seasonal ranger Leonard Landa.

“They were talking so fast and were so excited that it was hard to tell what was going on,” Landa said.

Once Landa determined they were talking about a separate bear attack from Granite Park Chalet, he contacted park headquarters and announced that he was heading to Trout Lake. Landa asked two of the hikers to come along to direct him to where they had camped. The three arrived at the lake at about 10 a.m. and began yelling for Koons. On the beach, they found four sleeping bags. Minutes later, they discovered Koons’ sleeping bag, bloody and torn, about 20 feet from the others. They went deeper into the woods, where Landa spotted a small piece of flesh. He followed a trail of blood into the brush and found Koons’ body, about 40 feet from where she had fallen asleep the previous night.

Not long afterward, Bert Gildart arrived. Earlier, Gildart, a seasonal ranger, had been helping guide a piece of firefighting equipment over Going-to-the-Sun Road when he heard a ranger at Granite Park frantically trying to get ahold of headquarters to report a bear attack. Gildart helped relay the message on his radio and then continued down to West Glacier. After a few hours of sleep, Gildart was woken up by another ranger and ordered to respond to a bear attack at Trout Lake. Confused, Gildart responded that the attack had happened at Granite Park. The ranger told him there had been a second mauling.

“I just couldn’t believe it,” Gildart said.

Gildart and Landa loaded Koons into a body bag that had been delivered by helicopter. The body was flown to West Glacier and turned over to the local coroner. Landa helped the two hikers gather items they had left behind and then directed them to hike out with a horseback rider. Landa and Gildart continued on to Arrow Lake, another three miles up the trail. There they found a group of hikers and gave them an armed escort back to Lake McDonald.

By the time Gildart and Landa arrived at Lake McDonald that evening, news of the Trout Lake attack had spread. T.J. Tjernlund was a 16-year-old dishwasher at the lodge and often spent his free time chatting with the girls at the gift shop, including Koons, who was friendly and widely liked. On the morning of Aug. 13, rumors were flying around the lodge about a death at Trout Lake.

“We were in the dining room that afternoon when one of the girls walked in crying and said, ‘It was Michele,’” Tjernlund said. “Everyone felt numb after that.”

“I went down to the lake and sat there for a while, just trying to absorb what had happened,” Voris said. “It seemed impossible to lose someone you were so close to.”

The following day, Gildart and Landa were ordered to return to Trout Lake and find the bear that had killed Koons. At the lake, they set out cans of fish, but after the bear hadn’t appeared for a few hours, they continued on to the Arrow Lake shelter to spend the night.

Gildart woke up around 5:30 a.m. the next morning and went outside to go to the bathroom. In the pre-dawn light, Gildart spotted a large female bear 40 to 60 feet away.

“Leonard,” Gildart called out, “get the guns.”

Unafraid of the two men, the grizzly walked toward them. As it inched closer, the two men raised their rifles and opened fire, killing the animal. They radioed headquarters to report the shooting. A biologist and an agent with the Federal Bureau of Investigation arrived later that day by helicopter to recover parts of the bear, including the head, claws and stomach contents. When they cut into the sow, they discovered a clump of blond hair, leaving no doubt that it was the right bear.

Later that week, Gildart made a third trip to Trout Lake to pick up the trash that had initially attracted the bear. They filled 17 burlap bags. Fifty years later, the mounds of garbage from Trout Lake remain one of the most enduring images of that summer for Gildart.

“The 1967 maulings changed everything,” Gildart said recently. “Bears were looked at very differently after that.”

In 1968, journalist Jack Olsen wrote a three-part Sports Illustrated series about the attacks that was later turned into the book, “Night of the Grizzlies.” In it, he stated there was a one-in-a-million chance of two fatal bear attacks occurring so close to one another on the same night. For a long time, Gildart believed that, but over time he has changed his mind.

“The more I thought about it over the last 50 years, the more I realized that it was only a matter of time,” he said. “It was inevitable that there would be a fatal bear attack in Glacier National Park.”

Bear Management

As the park’s first-ever research scientist hired weeks before the fatal attacks, Cliff Martinka’s charge on Aug. 13, 1967 was, at least initially, straightforward: “Shoot the bears. Pretty simple,” Martinka told the Beacon prior to his death in 2014.

Five grizzlies were shot and killed in the days that followed, including the two bears that rangers believed had killed Helgeson and Koons. But in the weeks and months to come, park management and the public started asking questions about grizzly bears’ relationship to Glacier Park and its visitors.

The inquiries turned up a dearth of information and a glut of misguided theories about what led to the attacks, including rampant speculation that lightning had provoked the bears.

The killings would eventually prove to be a bellwether event for bear management in national parks.

They also led to Martinka’s first research assignment.

“I started to do some work on grizzly bears,” Martinka said. “We were trying to piece together what the bear population looked like in those days, without having any technical information except some bear sightings. There was amazingly little work going on with grizzly bears.”

“In many respects,” he added, “that night kind of defined my career.”

Two weeks prior to the fatal night, David Shea, a park ranger and biologist, hiked to Granite Park Chalet on three occasions, instructed by his supervisors to report on the “garbage disposal situation” and to observe grizzlies in the area.

“They were putting out food because it was entertaining,” said Shea, who spent 36 years working in the park. “I can’t believe it’s been 50 years, but a lot of good has come out of that tragic night. I can remember when Glacier’s bear management plan was three pages long. Now it’s around 50 pages, and grizzly bear research has been a major focus.”

Along with Martinka, Shea joined Chief Park Naturalist Francis Elmore, research biologist Robert Wasem, naturalist John Tyers, and seasonal ranger Kerel Hagen on a mission to Granite Park Chalet, where over the course of three days the men would shoot and kill three grizzly bears.

“As a biologist and naturalist, I really like bears,” Shea said. “They are curious and intelligent animals, and I didn’t enjoy killing them. But those bears were so tied into humans and garbage, they had come to associate the two.”

Following the deaths of Koons and Helgeson, the park established a pack-in, pack-out policy for food and garbage, eliminating dispersed camping and establishing designated campgrounds, as well as designated cooking areas. Park officials installed wire cables so that backcountry campers could hang their food, and launched an aggressive bear education program.

“There is Glacier National Park before the Night of the Grizzlies, and there is Glacier National Park after the Night of the Grizzlies,” said Jack Potter, a 41-year employee of the park, who retired in 2011 as chief of science and resource management. “It changed everything.”

It’s a sentiment that has not been lost on friends and family of Koons and Helgeson.

“Michele was instrumental in changing how the National Park Service managed bears,” said Michele’s younger sister, Krista Petersen. “I think that’s something she would be proud of.”

Petersen was 13 years old when Koons died, but she still remembers her older sister as someone who was full of life and adored by all.

“She was cute and perky and funny and all that,” she said in an interview last week.

The two deaths received heavy media attention almost immediately. Television networks sent correspondents to Montana, and the story appeared in nearly every newspaper in the nation. Petersen said her parents worked hard to shield Koons’ three younger siblings from the attention, although her mother kept an envelope with stories about the incident.

One year younger than Julie Helgeson, Laurie Helgeson George recalls her favorite cousin’s magnetic and outgoing personality, which was evident in the last letter she ever received.

“I had just graduated from high school and she had finished her freshman year of college, and she was describing her upcoming trip to Glacier Park and how excited she was,” George said. “When it happened, I can remember it like it was yesterday. I heard my dad yell and I ran downstairs. I can remember watching Walter Cronkite on CBS News talking about it. It was the main headline because it had never happened before, but when it happens to someone who you love, who has the same last name as you, it just hits so close to home.”

Over the years, people who knew Koons and Helgeson have reached out to the families to express condolences and convey memories.

A few years ago, Judy Voris — now Judy Fuglestad — spent several days in San Diego visiting with the family and remembering her roommate from the summer of 1967. This year, a man from Massachusetts reached out on Facebook to tell Petersen that he had met Koons when he was 11 years old, just a few weeks before she died. He wrote that he had been on a family vacation in Glacier and went to the gift shop multiple times to visit with her.

“My Dad liked us to go fishing, but my favorite pastime was going to the gift store,” the man wrote. “There was a girl there, a lot older than me, and I had a little boy crush on her. She was sweet and friendly and each time I came by, she always made me feel like I was the most important person she had run into that day. I made any excuse to go to the gift store at least twice a day to buy gum and candy. Of course, I didn’t need more — I just wanted to talk to the girl that made me feel special.”

In the weeks before the fatal bear attacks, both Koons’ and Helgeson’s parents visited their daughters in Glacier National Park, and saw firsthand how happy they were working and playing in its wild and pristine environment.

“Julie’s parents talked about what a good time she was having, and her love of nature, the people and the animals,” George said.

After Helgeson’s death, Father Tom Connolly, the priest who held her hand and prayed with Helgeson while she lay dying on a table in Granite Park Chalet, visited her parents in Minnesota. He told them that while it was tragic, Helgeson died surrounded by beauty.

“I think that brought them comfort,” George said. “That she was in such a beautiful place.”

Petersen said Koons’ family camped, saw where she worked and met her friends. Even a half-century later, Petersen said it was clear that her sister loved being in Glacier.

“Michele lived a lot of life in 19 years,” she said.

Editor’s Note: This narrative is based on numerous interviews with witnesses, as well as National Park Service incident reports compiled after the tragic events and made available to the Beacon through a public records request.