The walls of Josh Fields’ house are filled with trophies.

These relics protrude from the crisp, clean walls, the most eye-catching features in a spacious, well-kept home outside Columbia Falls. The trophies were earned by Fields, secured by Fields and are displayed by Fields.

These things we keep are reminders of conquests, treasures acquired through patience, skill and determination. They are carefully selected to tell particular stories, about our lives, our passions and our achievements.

Asking the 38-year-old Fields about the trophies on his walls elicits plenty of stories.

“The buffalo was a special permit that I drew in 2006,” he says. “And these elk here are local bulls … The moose, I was fortunate enough to draw the tag, and that’s (from) just right here in the North Fork, too. All local stuff and fair chase, public land, just the way I grew up doing it and the way that I’ll keep doing it.”

There is also a mountain lion, and some mounted bucks, all harvested by Fields with his bow. He calls archery hunting his “passion” and being out in the woods his “church.” He is a dedicated archer, with a faux deer riddled with arrow holes in the driveway to prove it, and he and his wife chose their home in part because it is in the kind of untamed territory where Fields does his hunting.

But the house also holds other trophies, different from these. A handful are sparsely displayed upstairs, in a small, unremarkable room, and the rest are in boxes in the garage, shielded from prying eyes and revealed only to those who ask to see them, or more precisely only to those who know to ask for them at all.

These trophies tell a story, too: that Josh Fields is the greatest professional baseball player Northwest Montana has ever produced.

Fields is not hiding his professional baseball past; it only appears that way because he’s so reticent to make a big deal out of a prior life, one that ended 10 years ago.

“You really hate to talk about yourself,” Fields says. “I’ve always been that way. My grandma always said, ‘You never talk about yourself; you always wait until you’re asked.’”

In his first life, Fields reached uncommon athletic heights despite not being blessed with uncommon physical traits. His Baseball-Reference.com profile lists him generously at 6-foot-1, and while he dominated Flathead Valley American Legion baseball as a teenager, his fastball topped out around 85 miles per hour — excellent for Montana but subpar by professional or major college standards.

Still, Fields was a three-sport athlete at Columbia Falls High School, going from quarterbacking the Wildcats football team on to basketball season and then to Glacier Twins baseball. His head coach with the Twins, Julio Delgado, said that while Fields was undersized, “maybe 145-150 pounds soaking wet,” he showed potential from a young age.

“Everything about him, you could tell that he had some ability,” Delgado said. “As he matured and grew stronger, you could tell that he had a chance.”

“I had, I think, some of the intangible instincts that you really can’t teach because I watched the game and I played the game every day,” Fields said. “I was with my uncles and I was learning and learning and learning.”

Fields grew up with family all around him in Columbia Falls and started throwing a baseball as soon as he could walk. He would cry when it rained as a child because it meant he couldn’t go outside to play. Even as he aged, Fields’ love of the game never wavered.

“Freshman year of high school, you write down what you want to do,” Fields remembered. “Mine was, ‘I want to be a professional baseball player.’ I still have it today. That was all I ever dreamed or thought about, really. Maybe I’m just one of those weird kids or something, but that was it. There was nothing. It was baseball or nothing for me.”

Standout athletes in Montana, particularly baseball players, have few options collegiately even today, and it was that much more difficult when Fields was in high school, before the internet and social media connected athletes from the most remote locations to recruiters around the country. Fields graduated high school in 1998 and knew that he wanted to find a college where he could challenge himself.

“I wanted to be able to play with the best or I’ll come home,” Fields said. “I didn’t want to go someplace that wasn’t recognized or I really wouldn’t have the opportunity to be seen by professional scouts and really test my skills.”

Fields wound up, with an assist from Delgado, at one of the best junior college programs in the country, Mesa (Arizona) Community College. Baseball-Reference.com lists 31 Major League players who have come from the school, including Mike Deveroux, Mickey Hatcher and Shea Hillenbrand. But Fields went to Mesa with no guarantees of even making the team, let alone having the type of success that would lead to a professional opportunity.

“(Delgado) was a big part of me getting a workout down there,” Fields said. “He had told me before I left here, ‘You’re going to go down there, you’re going to make that club and you’re going to stay there. You’re not going to quit.’”

“Coming from (Montana) and being a state MVP and all of that, I was maybe the least-talented kid down (at Mesa),” he continued. “I don’t want to say it was a shock, because I had traveled a little bit before I went there, but in the baseball world it was night and day.”

Fields, of course, ended up making the team and starred at Mesa where he received professional-caliber guidance from his pitching coach, Zeke Zimmerman, now a coach in the Los Angeles Angels minor league system. Zimmerman helped Fields fine-tune mechanically and add zip to his fastball, which would top out in the low-90s as a professional.

Just as he had hoped, Fields was seen by dozens of scouts at Mesa. However, despite the high level of competition, interest in Fields from big league clubs was still fairly minimal. Ahead of the 2001 Major League Baseball Entry Draft, the right-hander had personal workouts with just three teams — the Colorado Rockies, Tampa Bay Devil Rays and Chicago White Sox.

“I knew I wasn’t going to be a high-round pick, but I was a guy that just wanted an opportunity,” Fields said.

That hunger was evident in the eyes of at least one professional scout, John Kazanas, who has been evaluating players for the White Sox since 1988 and has signed, among many others, all-star pitcher Mark Buehrle.

“One of the first things is he’s one of the better competitors,” Kazanas said of Fields. “He wasn’t that 6-foot-2, 200-pound kid that really had great velocity and stuff, but he acted like he was. His makeup in competing and trying to get better was outstanding. There’s not a category on your (scouting) sheet about what’s in his heart, but he was a nasty competitor.”

Kazanas convinced his bosses to pick Fields in the 23rd round of the 2001 draft. When Kazanas announced on a conference call filled with scouts from every other major league organization that the White Sox were taking a kid from “Hungry Horse, Montana,” those on the line burst into laughter at the town’s bizarre name.

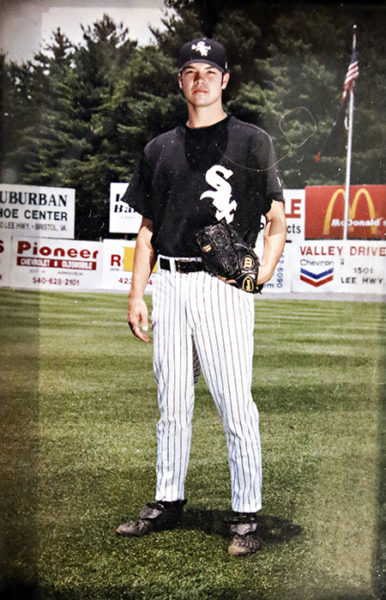

Fields was in Bellingham, Washington, playing for a wood-bat summer league team when the call came that he had been drafted. He was in a small hotel room, with his roommate sleeping in the adjacent bed. Fields signed his contract almost immediately and began his professional journey with the club’s rookie league affiliate in Bristol, Tennessee shortly after that.

“That was an eye-opener,” Fields said of Bristol. “I think that was some of the worst numbers I ever put up. Guys were smarter, (hitters) started to really think and I couldn’t just get by with my stuff now. I had to learn how to pitch.”

Thankfully for Fields, he was a quick study. By the next season, Fields was a key piece of the bullpens in Low-A Kannapolis and High-A Winston-Salem, both in North Carolina. In 2003, he was Winston-Salem’s closer and pitched the Warthogs to the Carolina League Championship that fall, closing games in the postseason.

An invite to the prestigious Arizona Fall League would come soon after, and a promotion to Class AA Birmingham in 2004 where he faced off against some of the best prospects in the sport — and thrived, appearing in 52 games for the Barons and posting a 2.55 ERA and tidy 1.01 WHIP. He was on the fast track to the major leagues, with what was becoming one of the top organizations in baseball. The White Sox would go to win the 2005 World Series.

“When I was at my best, it was a video game,” Fields said. “I could put [the ball] wherever I wanted, whenever I wanted at some point in my career. I could do that. That’s what they do up there and that’s what people talk about. You don’t realize how talented they are. It’s unbelievable.”

Ken Kolanowski is near Fields in age and he, too, has lived more than one professional life. He is a former sports agent and met Fields in the fall of 2003, just a few years after Kolanowski’s own playing career had ended and he was breaking into the business of player representation.

“He had some great success starting off and needed some guidance,” Kolanowski said of those first interactions. “That was the first client I recruited, and that’s one of the reasons he was so near and dear to my heart. He was as committed to me as I was committed to him.”

Everyone, it seemed, who came across Fields had a positive story to share, whether it was about signing autographs longer than needed, about hunting trips taken together in the offseason or about his refusal to relent in the face of long odds. Perhaps that affection was, in part, because of his underdog story of a small-town kid from a non-traditional baseball region about to defy all of the odds. In more than 130 years of baseball history, only 23 Montana-born players have reached the major leagues, according to Baseball Almanac, but Fields was about to join that group.

It’s what made what happened next that much more heartbreaking.

“(It was) 2005, Charlotte and Richmond Braves,” Fields says, his voice catching. “I’ll never forget it. Aug. 11, I want to say.”

“Freaking, like, 20 days away from September call-up, man, but you don’t know that or realize that at the time.”

Fields started the 2005 season with the Triple-A Charlotte Knights, the final level before reaching the big leagues, and he was as successful there as ever. He pitched 68 1/3 innings over 55 appearances in Charlotte, with a 2.75 ERA and 1.19 WHIP. He and his agent, Kolanowski, had been told it was only a matter of time before he was going to be called up to Chicago, and that was almost certain to happen come Sept. 1 when major league rosters expand from 25 to 40 players.

But then came Aug. 11, when he had to leave a game due to a shoulder injury.

“I just wore down,” Fields said. “It’s so long ago now that I think it’s almost suppressed, the bad part of it, but I was hurting pretty good and I was probably hurting for a while. I think I was broken down at that point and I was like, ‘Man, I just need to get fixed and I’ll come back.’”

“When the first [injury] came through, it was so close and it was just heartbreaking,” Kolanowski said, still emotional all these years later. “I knew he was getting tight and having some tenderness. I remember that call and he broke down on the phone (and said), ‘It’s over. I busted my labrum.’ He was running on all cylinders and the best he could have been at that time. It was heartbreak for him; it was heartbreak for me to go through that.

“He was crushed. As much as you can imagine times 10.”

Fields did tear the labrum in his right shoulder, an injury that even today is often career-ending. Still, the Montana kid did not give up right away. The late super-surgeon Dr. Lewis Yocum performed two operations on Fields, and he did actually return to a professional mound, although he was never the same. In a professional career that lasted eight total seasons and spanned 266 games, Fields made only 26 of those appearances after 2005.

Baseball is a cold, cruel profession, and the White Sox released Fields early in 2007. It is a results-based business, and after surgery, no matter how many people in the organization liked him, or how competitive he was, Fields was no longer getting results. His dream was over.

“Your window is short,” Fields says today. “Mine was a 20-day window to make the big leagues if I look back at it now. When I went down that day … that was my window.”

The windows in Fields’ house showcase the splendorous greenery and mountain peaks outside his home. A look inside those windows shows Josh Fields, family man, playing with his two young boys and chatting playfully with his wife, Carla.

The two of them met right as Fields’ career was ending, in 2008, and he was preparing to retire from baseball and come home to Columbia Falls. They were married in 2012, and had their first child, Keller, in 2016 and their second, Reid, earlier this summer.

Carla, a nurse, is also a Columbia Falls native, and says she would have loved to see her husband pitch as a professional. But Josh, in most ways, is happy to share his new, second life with Carla and to have avoided mingling that relationship with his all-consuming job as a baseball player.

“She really knows nothing about this career that I lived, which is also a good thing,” he said. “You have to be selfish (playing baseball). It’s this or nothing — you really don’t have the time or the energy to give to anything else, especially in my position where you didn’t get a million bucks to sign.”

In his eight professional seasons, the most Fields ever made was playing in the Venezuelan Winter League, where he earned less than $10,000 per month. Fields lived with host families throughout some of his career and scraped by on mostly meager wages, plus $20 a month that Kazanas would mail him and the occasional player perk, like the gift certificate to a Mexican restaurant he once won for being named his league’s Pitcher of the Month.

“Ask him how much money he had when he met me,” Carla quips, overhearing the conversation. They both laugh.

Fields has a day job today, working for the City of Whitefish, but the job he cherishes most is as a dad. His eldest son already has a baseball bat and ball he totes around the house, and for Halloween last year father and son both dressed up as Josh Fields, professional baseball player.

“There’s nothing better (than being a dad),” Fields says, beaming. “I’m blessed with two boys now — happy, healthy boys — and it’s good, man. It’s real good.”

“He’s the best dad,” Carla lovingly adds.

In the years since retirement, Fields has stayed mostly out of the sport he still loves. He coached a youth baseball team for a short while and says he would like to do that again, especially once his sons are old enough to play. But for now this new life is his priority.

“It feels like 1,000 years ago (that I played baseball),” Fields says. “It was good to get away. I didn’t want to be defined by that.”

Fields can look back on that career without regret. There is disappointment, to be sure, that he didn’t reach the big leagues, didn’t enjoy stardom there and didn’t make the kind of money that could have set him and his family up for life, but there is not regret. And there is no feeling of failure.

“Put it this way: I don’t need anybody to tell me I’m good,” he says. “I know what I did was pretty special, and the people that are close to me, old coaches and things like that, they remind you, but I don’t need to be reminded of that … I’m very proud of what I accomplished.”

“He beat a lot of odds to get to where he did,” Kazanas said. “He was one of those guys.”

Read more of our best long-form journalism in Flathead Living. Pick up the fall edition for free on newsstands across the valley.