“Aw, the Byrds all want to fly,” Maureen Byrd says, the irritation in her voice obscuring the unwitting pun she’s delivered. “The ground is not fast enough.”

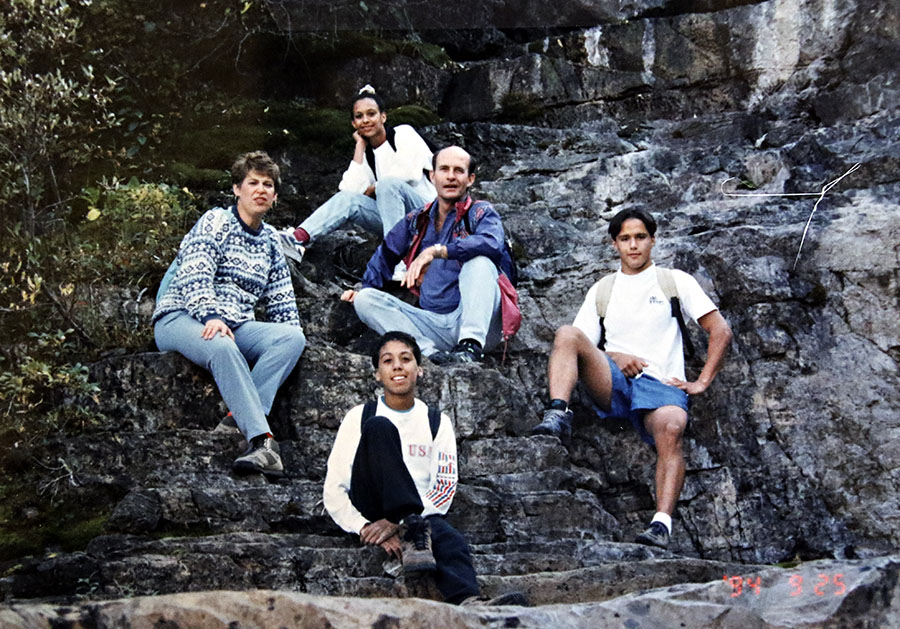

Byrd is, in this moment, seated around a large dining room table with her youngest son’s arm around her shoulders and her two other children — and their three spouses — ringing the rest of the table. They have been smiling, laughing and joking for hours, pouring glasses of red wine and sharing stories about their lives and the life of a man sitting just a few feet behind them, on a recliner, with his grandchildren playing all around him.

The man, Maureen’s husband Chris, is the source of Maureen’s irritation, or at least he was some 20 years ago when he brought home a RANS airplane kit, a 10,000-piece puzzle that would one day become, he hoped, a functional way for this Byrd to soar. Chris worked on his plane for years, painstakingly assembling the fever-dream equivalent of an IKEA bookcase. The plane came with a 1,000-page manual, and Chris read every word, jotting down notes in the margins as he went along until one day, around the turn of the 21st Century, it was finished, so he took the plane to a small airstrip near the West Glacier KOA and prepared to spread his wings.

Chris was a licensed pilot but it had been at least 10 years since his last flight, and, preparing to take the maiden journey in a plane he assembled himself, his wife and two of his children came along to watch the spectacle and, grimly, to know where to look for his body if things went sideways.

Almost immediately, things went very sideways. Maureen screamed as the plane rose from the airstrip, tilted violently and dove directly at a thick patch of trees.

“I thought for sure he was going to crash,” Maureen says.

Chris did not crash, though, and once he mastered the controls, he ended up playing in the wilderness for hours, practicing landings in the backcountry while his family was waiting back at the airstrip, unsure of when, or if, he would be coming back.

He did come back, of course, because he always did. When he was 14 years old and drove the 430 miles to Enterprise, Oregon by himself on a tiny 50cc motorcycle to work on a farm, Chris came back. When he hopped on a pogo stick to his family’s store and continued to pogo down the aisles as he shopped, he came back, still pogoing. When he was working at the Hungry Horse Dam, a job he loved, and decided to tiptoe around the dam’s glory hole for still unknown reasons — a ludicrous stunt that, had he fallen, would have certainly killed him — he came back.

“One of the most confident human beings I’ve ever known,” O’Brien, Chris and Maureen’s oldest son, said. “Everything that he did was with full confidence. He never wavered. Never backed down.”

Bernida and Herman Byrd came to Northwest Montana to help build the Hungry Horse Dam, and in 1947 they gave birth to a son, Chris, who would years later tempt fate at that very same dam. Chris is one of 12 siblings, and he and his brothers and sisters added another 60 grandchildren to the brood a generation later.

In the late 1960s Chris matriculated to Carroll College in Helena where he took a freshman biology class and was partnered with a young woman, Maureen (herself one of 10 siblings from a farm in South Dakota), on the first day. They married in 1969 and will celebrate their 50th anniversary next year.

Chris eventually graduated from Montana State University in 1970 with a degree in plant and soil science, before he and his new bride joined the Peace Corps and were stationed in Ecuador, although they were, in Maureen’s words, “not successful volunteers,” struggling with the lack of structure that then plagued the Peace Corps program.

So they came back to the United States, settling shortly thereafter in a two-bedroom cabin just 500 yards away from the home where Chris was raised, and just a block from the family business. Byrd’s Food Mart, located where U.S. Highway 2 now runs through the Bad Rock Canyon, would become a staple of the region and employ a number of Herman and Bernida’s children, including Chris and Maureen. The shop included a laundromat, trailer park and butcher shop, where Chris cut game and Maureen wrapped it. Eventually, a liquor store opened inside, and Chris and Maureen took ownership of that business, later moving it to its own building and adding a second liquor store, Montana Liquor and Wine in Kalispell. Two of their children followed them into the family business, with Brenden taking control of the Kalispell store and O’Brien and his wife, Melanie, opening O’Brien’s Liquor and Wine in Columbia Falls, in 2004, four years before the family sold the Hungry Horse store.

The liquor and wine business was never part of the plan, but living in Northwest Montana was, and for the affable Maureen and hard-working Chris, they made a good pair in retail, serving their customers with aplomb, doing almost all of their own construction and, of course, recruiting their kids to help.

“If somebody had told me then that this is what you’re going to do for the rest of your life, I would have told them they were crazy,” Maureen said.

“We live where people come to vacation,” she added. “They get two weeks out of the year and we lived here year-round. And it was worth it.”

The land in Martin City that Chris and Maureen own, surrounded by other Byrds, is a spectacular piece of earth. And where once stood a cabin now stands a gorgeous house that Chris and Maureen built themselves, aside from the odd assist from a few family members to raise the walls. Off the kitchen, a large sliding glass door presents a breathtaking backdrop, something straight out of a Montana tourism brochure. There are snow-capped mountains, dense forests and a bucolic creek splintered from the Middle Fork Flathead River running through all of it.

Chris and Maureen would raise their family here, and years after that two of their children — O’Brien and Tiffany — would join them in homes nearby, a flock of grandchildren in tow. In the 70-plus years since the Byrds first landed in Bad Rock Canyon, jobs have not always been easy to come by, there has rarely been money to spare, but the family has persisted.

“That was the mentality of this Martin City/Hungry Horse area,” Brenden, the Byrds’ youngest son, said. “There’s a lot of other families up here, but the Byrd family’s stuck it out in tried and true times, when there was no income, when there was no economics here, they found a way to stick it out and stay and keep roots in this area.”

Brenden and his siblings are spending most of the evening back at the kitchen table cracking each other up. One story in particular has everyone roaring with laughter.

“I still have people ask me now, like, ‘I just don’t see you and your dad’s resemblance,’” Brenden says. “And I’m like, ‘Yeah, I’m not bald.’”

The punch line kills in this particular room. Brenden, tall and lean with a full head of hair, truly does look nothing like Chris, who is of average build and afflicted with male pattern baldness. That, and Brenden is dark-skinned, like his sister, Tiffany, and their brother, O’Brien, who has a medium complexion. Maureen and Chris are very white. The couple had talked about adoption from the earliest stages of their relationship.

“We just felt like (adoption) was something we could do and something we should do,” Maureen said. “So I never got pregnant, and then everything just kind of fell into place. It wasn’t traumatic for me or Chris; he didn’t care if we adopted or had our own. He was very happy with adoption.”

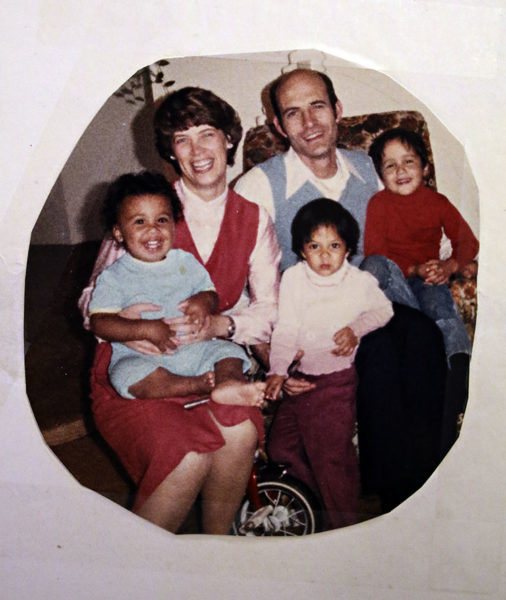

It was an advertisement in a church newspaper that first alerted Chris and Maureen to Catholic Social Services, an adoption agency, and not long thereafter they received a letter in the mail telling them that their son, O’Brien, was ready to be brought home. The family of two became three when O’Brien was two months old, in 1977, and their lives changed immediately.

“It was a religious experience for me,” Maureen said. “I wasn’t prepared for how much I loved him. I thought I’d love him like I love my brothers and sisters, and it was totally different. It gives me shivers right now. It was really amazing.”

Not long after, Tiffany and Brenden joined their older brother, and from the very beginning all three of them knew they were adopted, and all three now know who their birth families are, at Maureen’s urging. It never was, and still isn’t, a big part of any of the children’s identities. Years later, in fact, Brenden and his wife, Megan, would adopt a daughter, also via Catholic Social Services.

“I forgot I was adopted for 99.9 percent of every day,” O’Brien said. “That’s my mom, that’s my brother, that’s my sister. The fact that we were brown — really brown in the summers — (and) our parents are really white didn’t even dawn on me. Like I never even thought about it.”

That did not mean everyone else in town was so colorblind. O’Brien was called the n-word by a classmate in second grade, and ran home when the boy and two friends challenged him to a fight after school one day. When he got home, Chris asked him why he ran. The next day, when the same thing happened, O’Brien punched the boy in the face. That was the end of that.

There were a handful of other moments tinged with racism, but for the most part the kids said they were unbothered growing up, something they almost certainly owed in part to the fact that they were in the Byrd clan. Herman, their grandfather, was a noted community leader — the boys said they once talked themselves out of trouble when a cousin asked a furious homeowner if he knew Herman Byrd — and the children grew up surrounded by a group of at least 10 intrepid cousins who stuck closely together. It was an upbringing that sounds like a work of fiction.

“Did you read ‘The Adventures of (Huckleberry) Finn’ as a kid?” Brenden asks. “OK, (our childhood) pretty much followed right along the line.”

The family almost never watched television, had no video games in the house and would gather together for breakfast and dinner daily. In between was pure freedom.

“You’d wake up, have breakfast, meet the cousins and disappear until somebody had to be somewhere,” Brenden said. “It’s just amazing to imagine, as kids, to have almost a 30-acre piece of Forest Service property that surrounds (you) to run free and wild.”

And, as one might surmise for the children of a man who lived most of his life without fear, there was no shortage of childhood adventure, whether it was riding motorcycles, getting pulled behind snowmobiles or jumping off cliffs.

“If I ever needed money to, like, go out with a girl, I would go to (mom),” O’Brien said. “If I ever wanted to go camping with my buddies or take my motorbike somewhere, I’d ask dad.”

In May, Chris Byrd hopped in his car and drove away, and his family was terrified that this time he would not come back.

It was a decade ago, in hindsight, that Maureen says she and her children first saw the signs that something was wrong. For Chris’ wife, it was the way he obsessed over the building of their Kalispell liquor store, so much so that he skipped a planned trip to visit his daughter and son-in-law, then living in South Korea. For Chris’ two boys, both high school soccer coaches, it was the way their dad lost track of their seasons, something he used to follow closely.

“You’re just not listening, you’re not paying attention, you don’t maybe care as much any more,” O’Brien remembered thinking. “But when mom first said, ‘Hey, I think dad’s got dementia,’ I started thinking, ‘Oh my God, that makes more sense.’”

In 2014, doctors discovered shrinkage in the frontal lobe of Chris’ brain, an incurable, irreversible degradation of the confident, brilliant and thoughtful man who built almost his entire life with just his bare hands. Doctors told Maureen they believe the shrinkage is related to a trauma, but no one is sure what that trauma was or when it happened, and it wouldn’t matter even if they did.

“For me it’s been every day, just enjoying every little moment that I have with him,” Tiffany said. “And just loving him the way he is.”

These days, Chris spends loads of time with his grandchildren, who watch the same cartoon over and over again, an experience their grandpa doesn’t seem to mind. As his condition has worsened, the family has purchased a watch he wears that tracks his location, and Maureen now needs to bathe her husband, who has fallen in the shower more than once. But, they say, Chris seems at peace.

“I am really grateful that he’s happy; well, not happy, he’s content,” Maureen said. “He’s not happy, he’s not sad. He just is.”

When Chris jumped in the car and took off in May, his watch wasn’t tracking his location. No one had any idea where he was. A bulletin was put out by the Flathead County Sheriff’s Office and local TV stations shared the alert. He made it all the way to Eureka, somehow, before he was discovered, safely, but along the way the Byrds heard from dozens of other family members, friends and even total strangers who knew the family, knew of the family, or just wanted to help.

“That’s how deep this family is in this area,” Brenden said. “It was amazing the phone calls from random people, like, ‘What can I do?’”

What the Byrds will do is keep on, keep building, keep serving their customers and keep together as a family. There are no plans to move Chris to a convalescent home — perhaps nothing sounds less Byrd-like — but instead to keep Chris involved as long as he can. When Chris’s dad, Herman, suffered a stroke late in his life, his sons still strapped him to motorcycles and snowmobiles, a whole half of his body limp, so he didn’t have to stop living all the way to the bitter end.

“There’s just so little of what he was like left,” Maureen said. “He’s still pleasant, thank God, but I think it’s been a hard adjustment for all of us. We miss him.”

Read more of our best long-form journalism in Flathead Living. Pick up the winter edition for free on newsstands across the valley.