High school sports have a big problem, and it has nothing to do with the players on the field. It has nothing to do with the fields and gyms where the games are played, with the hours required of stretched-thin student-athletes and coaches, with the increasing costs of equipment, travel and private coaching, with the inherent injury risks associated with sports, and with big-money outside forces threatening to undermine the entire prep sports construct, although those remain concerns.

No, the most critical problem with high school sports is with officiating and, no, it isn’t that they blow every call, don’t know the rules or are out to get your son/daughter/niece/nephew/friend/neighbor’s team because of some unseen bias.

But the problem with officiating is so dire that it could change some of the fundamental ground on which prep sports is built. It could move football’s famed Friday night lights to other nights of the week, could jeopardize the safety of the student-athletes on the field of play and could put at risk the tenuous order of game competition that helps teach the lifelong lessons learned through sport.

It’s a problem that is not new to the people who are part of the profession, and one completely lacking a clear solution. And it’s one that has been getting worse, in the minds of almost every prep sports stakeholder, and putting so much pressure on the piping that connects schools and athletics to the community they serve that the whole system is threatening to burst.

There is a persistent and pervasive problem in modern refereeing: There just aren’t enough of them to go around.

“As I have stated before, I don’t think that the schools … will begin to change until the system crashes and we have games cancelled because we no longer have officials to cover them,” one regional referee director in Montana put it, in an email to the officials in his area.

“I believe we are right on the edge of the cliff statewide, and the edge is crumbling right now.”

The National Federation of State High School Associations (NFHS) launched a major campaign to attract new officials in 2017, including a website (www.highschoolofficials.com), hashtag (#becomeanofficial) and targeted outreach, and while the program has been modestly successful, the country still faces a drastic officiating shortage from coast to coast.

“We talk, nationally, all the time when we get the 50 state directors get together, about officials,” said Mark Beckman, the executive director of the Montana High School Association, commissioner of the Montana Officials Association (MOA), current NFHS president and a former official himself.

As of Aug. 23, there were 1,319 officials registered to work in the state of Montana for the 2019-20 season, a number that should rise to approach the 1,630 officials registered last year once additional winter and spring sports officials sign up. It’s an improvement insomuch that the numbers are not in decline, but even 1,600 puts an undue burden on referees who need to cover games at the more than 170 member schools in the state, and it’s a stark drop from the 1,947 officials who were registered for the 2016-17 season. Worse still, officiating shortages exist in just about every sport and in just about all of the 11 geographical areas by which Montana officials are divided.

The state’s officials in the six sports that require sanctioned judges — football, basketball, wrestling, volleyball, soccer and softball — are overseen by the MHSA, MOA and the 11 regional directors, but the actual game assignments come from local, sport-specific pools. The Kalispell pool falls within Region 1, and its malleable footprint can mean those officials are responsible for games at Flathead, Glacier, Whitefish, Columbia Falls, Bigfork, Eureka, Thompson Falls, Plains, Polson, Ronan, Libby, Troy, Hot Springs and Noxon high schools, sometimes assisting other pools and sometimes asking other pools to chip in here. Further complicating matters, certified officials also work nearly every junior varsity, freshman, sophomore and middle school game — those contests are vital for training the next generation of referees — plus contests at non-MHSA schools like Stillwater Christian.

As the 2019-20 season gets set to kick off, there are only 158 total officials, spanning the six sports, registered in Region 1. There were 191 officials in Region 1 at the end of last season, and while the local total may approach that number again by the end this year, it still represents a total well below a level that would make everyone comfortable and confident in the pool’s ability to cover all the games.

There are three levels of officials in Montana — apprentice, certified and master — and only the top two levels, certified and master, are recommended to work varsity contests, according to the MOA handbook. In football, the state’s most popular sport, which kicks off on Aug. 30, the officiating shortage is at a critical level. The Kalispell pool has only 17 certified and master officials, and five-man crews are the absolute minimum required in a varsity game to maintain order and player safety. Having only 17 available varsity officials is as low of a number as Warren Dobler, a veteran referee gearing up for his 31st season and a former head of the Kaispell pool, can remember.

“That’s getting right down there,” Dobler said. “When I first started I think we were upwards of 25 plus, and usually 22-23. That was pretty good, but the last few years it just keeps bumping down.”

Activities directors around the Flathead Valley are used to having to go outside of the local pool to find officials, but this year even that might be a struggle. Officials prefer not to have mixed crews — some from one pool and some from another — because of familiarity concerns, and that means the 17 Flathead Valley officials can only work three games per week, likely all of which are scheduled at the same time, on Friday nights. Kalispell pool scheduler Joe Sullivan said there are 198 football games in the Kalispell pool’s coverage area this year.

As of the morning of Aug. 26, Bigfork High School Activities Director Matt Porrovecchio was still confirming officials for his team’s opening game (on Aug. 30), and Sullivan added that because of extreme shortages in Missoula, dipping into that pool, as is routinely done, may be a challenge this fall.

“(Missoula) lost seven officials, four of which who were master officials, and that’s devastating,” Sullivan said. “I texted (the Missoula pool scheduler) and asked, ‘You have any idea which dates you’ll need us?’ He said, ‘Every day.’ … They’ve gone so far as to tell schools down there you have to go Thursday or Saturday, or we can’t service you. And I’m afraid that we’re headed in that direction.”

And those fears are just over varsity games. Factor in sub-varsity contests, travel outside the pool area, conflicts with day jobs, injuries, illness, or the occasional request for a day off, and the numbers get tighter. In recent years, schools have had to regularly move game times or dates, and some sub-varsity games have had to be skipped entirely by MOA-recognized officials, instead either canceled or refereed by non-MOA officials, sometimes even parents from the crowd.

On top of the 17 certified and master officials, there are only five additional apprentices to help at the lower levels, even with three new refs signed up this year. It’s an equation that requires master officials to work not just varsity contests but almost all sub-varsity ones as well. Officials like Sullivan and Chris Parson, the head of the Kalispell football pool, a former helicopter pilot in the Marine Corps, the director of Flathead Valley Community College’s Continuing Education department, and a 10-year veteran football official, have to go to extreme lengths to balance refereeing with personal and work commitments.

“I typically do a double-header (on Fridays),” Parson said. “I’ll do a freshman game and then I’ll roll right into the varsity game. (You’ve) just got to; there’s not a lot of options.”

Parson said it’s not unusual for a football official to work a sub-varsity game on Monday night, another on Tuesday night, attend a study group with other officials on Wednesday night, add a third game on Thursday night and then work a doubleheader Friday. And they do all that in a job that requires good physical conditioning and even more mental discipline, even for a former Marine.

“It makes for a long afternoon and evening,” Parson said. “You’ve got to keep yourself focused in that second game, which is a key element, and that’s not easy.”

Todd Fiske, the Region 1 all-sport director and a basketball official with 30 years experience, says days can be even longer for hoops crews. He recounted the story of a three-man team from Kalispell being called to Noxon for a night, driving the nearly 150 miles to get there, then working the junior varsity girls game, varsity girls game, junior varsity boys game and varsity boys game, before getting back in the car and driving home. Officials make $60 for varsity contests — pay is less for sub-varsity and middle school games — and receive a travel stipend, but no matter the money, such a scenario is still far from ideal.

“We do four games on the same night; you come home, you’re just dead-ass tired,” he said. “Well, that’s not effective.”

Fiske said he sets aside the money he makes every year from refereeing for his family, and has used that money to pay for family vacations and outings with his wife. And that’s important, because since officials all work separate day jobs, then get taken away sometimes every night of the week, personal relationships can be difficult to maintain.

“I got to give kudos to my wife,” Dobler, the veteran football referee, said. “I mean, for 30 years she has let me, on Friday nights, go do my thing, and many other nights during the week. So that’s a family dynamic that each individual has to wrestle with as well.”

Dobler and Sullivan are both on the other side of 60, and Fiske has the scars of his own three-decade career, and their age makes them more the rule than the exception. Older referees have made it through the struggles of raising a family or advancing in their career while making time for officiating, two factors that cause loads of promising young officials to walk away from the job. But every year officials get older is a year they get closer to retirement, or face difficulty because of the physical realities of aging. Sullivan said two officials in the football pool have come back to work after bouts with cancer, and called he and Dobler’s generation “a Medicare group” while referencing his own two hip replacements and a knee surgery in recent years as evidence of the physical toll the work takes.

“You look at these guys reffing football, 90 percent of them have some fake joint or fake limb,” Porrovecchio said with a grim laugh. “They’re a dying breed and it’s hard to find people who want to put the time in. It’s a tough gig and it’s gotten tougher.”

Data on referee ages is not available in Montana, but no one is particularly encouraged about the current age breakdown that skews much more toward the gray-haired types. The primary stakeholders in prep sports identify two main areas of focus to change that: recruitment and retention. And the major impediment to improving either of those isn’t the schedule, isn’t conflicts with work — some games, particularly sub-varsity games, are played in the afternoon, before many employers are comfortable excusing their employees — and isn’t injury, although those all contribute. The main impediment is one you already know without reading another word.

“Why would I go make 35 bucks to get screamed at?” Grady Bennett asks, rhetorically, through a laugh. (Some sub-varsity games can pay as little as $25).

Bennett spent 25 years coaching basketball in addition to serving as the Glacier High School football coach since 2007 (and teaching at the school). Three years ago, Bennett stopped coaching basketball, decided to “make 35 bucks to get screamed at” and took the test to become a basketball a referee. His friends thought he was crazy.

“The first time I told them I’m going to get into officiating, they said, ‘Why in the world would you ever do that? Why would any human being want to do that?’” he said.

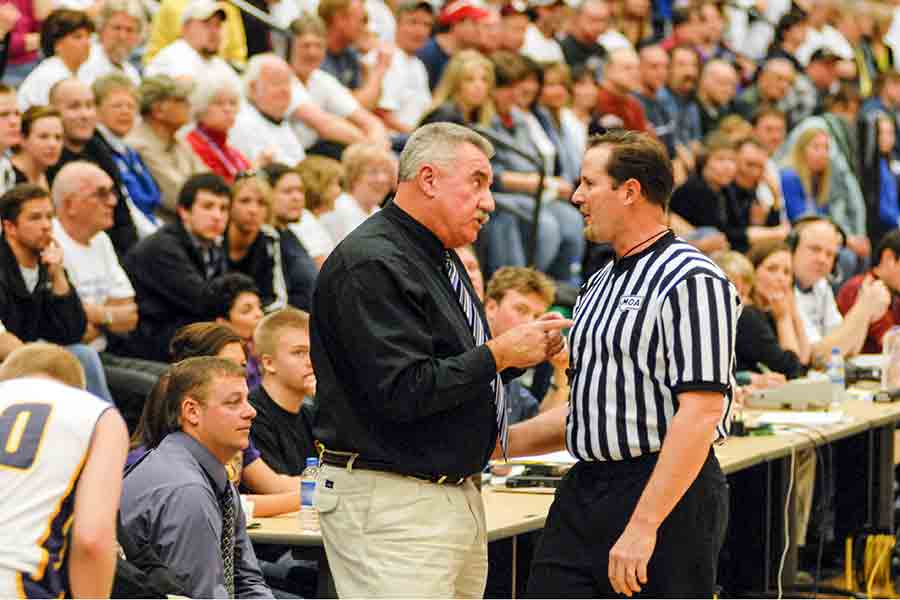

It’s a given, today anyway, that officials must deal with verbal abuse during games as a reality of the job. Fans, coaches and players, in descending order, are the primary offenders, and while it varies from sport to sport, it’s always there. Like the shortage in officials, it’s not a new problem, but it is one that is trending in the wrong direction.

The National Association of Sports Officials National Officiating Survey, completed by more than 17,000 officials from all levels and all sports in 2017, found that almost 57 percent of officials believe sportsmanship is getting worse, more than 64 percent had removed a spectator from a game, and a whopping 84 percent believe they are treated unfairly by spectators. (Coaches were not immune either, checking in at over 70 percent on the “treated unfairly” question.) Perhaps most troubling of all, an astounding 46 percent of officials reported they have “felt unsafe or feared for (their) safety” because of the behavior of players, coaches, administrators or fans.

“The work around good sportsmanship is a really big factor,” Fiske said.

No local official interviewed for this story recounted feeling unsafe in a game environment, but all of them had stories of out-of-control fans. Somewhat counter intuitively, they also reported that the abuse they receive is worse in middle school and sub-varsity games, a factor exacerbating retention problems.

“I had a couple of games this last year where our varsity refs helped out with sub-varsity basketball,” Bryce Wilson, Flathead High School’s activities director, said. “They came back afterward and said, ‘That’s worse than any varsity game I do.’ … One guy, he told me right then that, ‘I refuse to do a sub-varsity game again.’”

“You cut your teeth in the fifth, sixth, seven and eighth grade gyms,” Fiske said. “These little junior high games where there’s like 14 people and dad or mom are up there complaining, or a coach that’s complaining, you hear it all.”

Every official knows criticism comes with the job, and officials are fairly sympathetic to the hyper-competitive coaches, players, parents and fans who spit fire their way. Competitiveness is baked into sports, and when someone’s flesh and blood is involved, officials are patient so long as the offenders avoid personal attacks. But being insulted for hours can’t help but wear on everyone, especially officials who are new to the profession.

“When you look at it from the majority of people, it’s a good thing, because they’re supporting their sons or daughters in their activities,” Beckman, the MHSA commissioner, said. “But then always what happens, when there’s that intimate involvement, there can be ones that are saying, ‘I’m so tied up in this I’ve let myself go across the boundary line a little bit.’ They paid their money and they’re really invested and they’re emotionally tied to it.”

Ross Gustafson, the normally mild-mannered head coach of the Flathead basketball team, said he makes a goal every year of maintaining his composure when interacting with officials during a game. But even he is not immune to falling prey to his emotions.

“If you walked up and met (a referee) on the street, you’d never act that way,” he said. “That’s one thing I try to keep in mind because I run into these guys around town and they’re all great guys and gals, and you’ve got to remember that. That’s the challenge for me, is remembering that aspect in the heat of the moment.”

Through it all, the MHSA, the activities directors, schedulers, and referees have found a way to make it work, sometimes by shifting games to other nights of the week, sometimes by subbing in a parent on a sub-varsity game, and sometimes by paying extra mileage to bring in officials from out of the area. But something has to give.

Those working today in Northwest Montana do their best to sell the perks of the job, beyond just the extra walking-around money. Through officiating, they say they remain involved in the sport they love, stay in shape, impact the lives of young men and women by teaching the sport and teaching sportsmanship, and sharpen life skills like working under pressure, acting decisively and exercising patience. And above all, they boast about the camaraderie; officials run in tight circles socially, routinely gathering after games to swap stories over a burger and a beverage.

But no one has a good answer to the question of how this trend will turn around. The default seems to be that there will always be enough referees because, well, there have to be. Sure, the numbers have been declining, and the refs are getting older, and some day they’re all going to retire, and people don’t want to get screamed at for three hours, but there just can’t be competitive sports without them. And no one is predicting the end of competitive sports. The MHSA has a slogan it uses on materials to drive up referee recruitment: “Without referees, it’s just recess.” That’s a clever one-liner but unwittingly portends a future where games are conducted under the nearly lawless dog-eat-dog rule of the schoolyard.

All hope is not lost, however. Bennett, the Glacier football coach and newbie basketball referee, is one of the success stories. He’s someone who decided to take the plunge and do this, despite the busy schedule, despite knowing what the worst impulses of some coaches and fans can be, and says he expects to continue doing it for the foreseeable future.

“I really can’t convince anybody (else to do this) — I’m not kidding you,” Bennett said. “For me, it’s the passion of loving education and caring about young people so much and wanting to be part of the sport. I just like to help the kids out … It’s just kind of my passion in life.”

And maybe there are more people like that, and maybe there will always be, to keep the fields and courts of high school sports safe and orderly. Because without more people like him, the next time you load the car to enjoy a football Friday night, you might just be going to watch recess.

So You Want to Referee?

The Montana High School Association wants you to give officiating a shot, in one of the six sports — volleyball, football, wrestling, soccer, basketball and softball — that fall under the Montana Officials Association. To get started, fill out the brief questionnaire at www.highschoolofficials.com or call the MHSA at (406) 442-6010.

To become a member of the MOA, officials must pay annual dues ($65 for one sport; $30 for each additional sport), be at least 18 years old, and score 60 percent or higher on a rules examination. Officials must also purchase a uniform compliant with their sport and be “of good moral character.” To maintain membership, officials must attend at least six “study club” sessions annually in most sports. Officials in soccer and softball need only four study clubs per year.

In Montana, referees are paid $60 for varsity contests and are compensated 12 cents per mile for their travel. Drivers receive additional mileage for travel to games, paid at the federal rate.