Growth and Uncertainty

Kalispell Regional Healthcare is expanding across the Hi-Line while serving as the medical centerpiece for a large region amid a pandemic and preparing for the unsettling potential of fall flu season intersecting with a spike in COVID-19

By Myers Reece

In an April 30 introduction to a bid proposal to acquire Marias Medical Center in Shelby, Kalispell Regional Healthcare CEO and President Dr. Craig Lambrecht wrote: “The events of the last several weeks have forever changed healthcare as we know it.”

The long-term details of Lambrecht’s assertion will be further clarified in the coming years, but in the interim, nobody disputes the seismic shifts thrust upon the health-care industry in response to COVID-19. And as the medical centerpiece of a sprawling service area, KRH has felt and continues to feel the brunt of those reverberations in Northwest Montana.

Yet, KRH Chief Transformation Officer Cindy Morrison says the Kalispell-headquartered hospital system has demonstrated an adaptable resiliency partly rooted in an unlikely source: the turmoil of a highly publicized federal lawsuit and settlement that was accompanied by a leadership shakeup and a litany of newly imposed requirements, which ushered in changes to operational structures, processes, direction and decision-making.

That difficult but revelatory process laid a foundation of readiness that wasn’t immediately obvious in the initial upheaval of March and April but has crystallized since, according to Morrison, who Lambrecht recruited from Sanford Health, where they had both previously worked, last summer to help steer KRH through its transitional period — indeed, as her job title suggests, to guide the hospital’s “transformation.”

“You’re climbing toward a goal, and that first climb is steep, but at some point you top out and you begin to start to see the fruition of all those labors and all that decision making,” Morrison said. “It was because of that, all of those decisions we made starting last fall and all of those adjustments we made, all of that paid off wonderfully.”

Morrison praised the KRH workforce and leadership for embracing and executing those challenges, which set the stage for the greatest collective health care test they’ve faced: a global pandemic seeping into their backyard.

“I think it’s a testament to the people here who care about health care as a community asset,” she said. “To rally people around an idea and a vision, it’s not all roses. But we’ve come a long way, and I think that’s because of the people. I think it would be totally fair to say that our board and administration are very proud of them.”

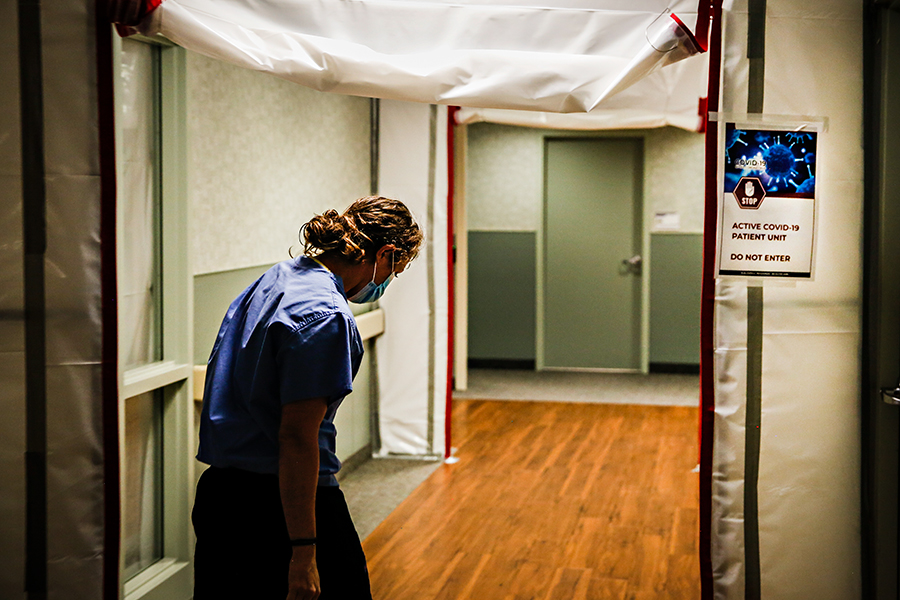

COVID Response and Impacts

When the first confirmed COVID-19 cases hit Montana in March, local health officials suffered from severe shortages of resources such as personal protective equipment (PPE) and testing, mirroring scarcities nationwide, while they also faced the prospects of combating a highly contagious novel virus with limited scientific research available.

Hospitals nationwide, including KRH, eliminated elective procedures and other services in order to prepare for worst-case COVID-19 scenarios. But as Montana avoided the surges seen in early hotspots such as New York, hospitals statewide began gradually re-implementing services in phases.

Rich Rasmussen, president and CEO of the Montana Hospital Association, said hospitals are still catching up on delayed procedures. Furthermore, the costs of tightening operations and eliminating elective procedures led to huge sums of lost revenue, some of which has been made up through federal stimulus and the return of services.

Rasmussen said a clearer picture of the precise financial damage will be available later this month when his organization releases a hospital survey that captures second-quarter losses.

Lambrecht announced in April that roughly 600 employees at KRH would be furloughed due to revenue losses expected to total $16 million per month without financial austerity measures. To date, since mid-March, the hospital says it has seen more than $30 million in revenue losses compared to last year, factoring in the expense-control actions, and continues to experience revenue declines.

Those losses have been offset by $30 million in federal stimulus funds, Morrison said, as well as the reintegration of non-COVID services. She said the “vast majority” of furloughed employees have returned to work, and while she couldn’t say whether the hospital will end the year in the black, she says the outlook is far better than a few months ago.

Beyond finances, Dr. Doug Nelson, KRH’s chief medical officer, noted the rollercoaster medical impacts of eliminating services, then reintroducing them and now beginning to limit them once again amid the recent uptick in COVID-19 cases and hospitalizations. Nelson said the changes are a response to the case increases and the potential for more moving forward.

“We have plenty of capacity in our hospital and we continue to do elective procedures, but we have started limiting the number of patients having surgeries that require hospitalization,” Nelson said last week. “We haven’t eliminated that by any means; we’ve just limited it because the future is uncertain.”

KRH has a dedicated 12-bed COVID unit, which has recently held as many as 10 hospitalized patients, plus an additional 18 beds with intensive-care unit (ICU) capabilities. If necessary, the hospital has options for further COVID-19 patient capacity, including 16 intermediate-care unit beds.

The vacant shelled third floor of KRH’s Montana Children’s medical center was repurposed into a temporary “alternate-care facility” to accommodate non-COVID patients in the event of a surge in COVID patients at the regular hospital. The U.S. Army Corps of Engineers oversaw construction of the project, which was completed in May and funded by the Federal Emergency Management Agency and state of Montana.

Nelson points out that fewer than 30% of COVID patients admitted to KRH have needed a ventilator, even if they have all been treated in the dedicated unit.

“It’s a minority of patients that have had to be ventilated and intubated,” he said.

Nelson cited a variety of examples illustrating the degree to which KRH and the region are better equipped to fight the disease than in the pandemic’s earliest months. For one, testing capacity and options have dramatically improved, although supply chains remain unreliable, and the hospital can now treat patients with remdesivir and dexamethasone.

More broadly, the hospital has had time to dial in its COVID procedures, while the epidemiology has also had time to mature.

“We’ve had a chance to hone our operations and plan and prepare for the potential of a large surge in patients who require hospital care,” Nelson said. “I think there’s no question we’re better prepared now to deal with a significant surge of COVID in our community than when we started in March.”

Eastward Expansion

At their June 11 meeting, the Toole County Commissioners unanimously accepted KRH’s bid to acquire Marias Medical Center in Shelby, which includes a critical-access hospital, the Heritage Center assisted-living facility and Brittan House staff housing, as well as the Marias Care Center skilled nursing facility, operated by third party EmpRes.

The commissioners selected KRH over Benefis Health System in Great Falls, which also responded to Toole County’s request for proposal.

Upon finalization, expected by the end of this year, those medical facilities will become subsidiaries of KRH, joining a health care system that already includes three hospitals — Kalispell Regional Medical Center, The HealthCenter and North Valley Hospital — plus Montana Children’s, Brendan House and Pathways Treatment Center. KRH also has what Morrison calls a “management agreement” with Cabinet Peaks Medical Center in Libby.

Northern Rockies Medical Center in Cut Bank and Pondera Medical Center in Conrad have also signed letters of intent to “explore a deeper relationship with Kalispell Regional Health and join the regional health network,” according to the 66-page acquisition bid proposal submitted to Toole County.

“The details of those partnerships will be synchronized with that of Marias Medical Center to ensure alignment and synergy across the network,” the proposal stated. “A regional health network will strengthen the ability for each entity to serve the healthcare needs of the local communities.”

The proposal also stated that KRH has engaged with Blackfeet Community Hospital, Blackfeet Emergency Medical Services and Glacier County Emergency Medical Services to “listen to their needs and challenges.”

The document notes that discussions with Hi-Line institutions intensified after KRH initiated and funded a Unified Incident Command Structure to help counties along the Hi-Line and Lincoln County “coordinate activities and communication” while providing “clinical resources, expertise and tools that rural facilities didn’t have.”

In the proposal, KRH described the scope of its current operations, including 354 total hospital beds, 47 clinics and 4,000 employees. Among those employees are 500 medical staff and 197 employed physicians representing 66 specialties. The physician figure is significant when considering that KRH didn’t employ a physician until 2009, as doctors were previously in private practice and non-hospital clinics.

Morrison noted that health care has been consolidating for decades, and hospitals elsewhere started taking private physicians into their employment ranks well before those in Montana did. Multi-state conglomerates are often leading the consolidation trend, rather than state-headquartered local hospital systems. If an entity such as KRH doesn’t step in, a bigger out-of-state system might.

“It’s the same recipe: If a large system was in here, they’d be making a similar pitch,” Morrison said. “The fact that Montana hasn’t been very consolidated yet is kind of unique.”

The relationships with other medical institutions bring KRH closer to its goal of becoming a fully integrated health care system, Morrison said. They also help the hospital achieve its ambition of remaining independent and locally controlled by virtue of building “economies of scale” and diverse partnerships, she added.

“You can do a better job when you’re united under one umbrella,” she said.

Morrison said the pandemic has exposed the “fragility of health care,” especially for small rural hospitals operating at razor-thin margins, and noted that COVID-19 might accelerate consolidation.

KRH had previous ties to Hi-Line hospitals, notably exemplified in its assistance provided to Marias Medical Center early in the pandemic when Toole County was struggling with an outbreak at a long-term care facility that killed six residents.

As for the expansion efforts occurring amid the uncertainty of a pandemic, Morrison points out that discussions with Marias, Northern Rockies and Pondera were in motion well before COVID-19, based on longstanding relationships. In the case of Marias, Morrison said both sides felt the timing was right for a deal, which they believe will enhance operations across the board.

“We believe it was a win-win,” Morrison said.

Rasmussen, CEO of the Montana Hospital Association, said KRH’s supply of resources and expertise to Marias Medical Center during Toole County’s early COVID-19 outbreak allowed the institution to weather the storm.

“Had they not stepped in and helped them, that facility was facing temporary closure,” Rasmussen said.

KRH says in the bid that it will establish a new 501 (c)(3) to acquire the assets of the critical-access hospital and commit certain funds “in lieu of payment of the purchase price,” including $1.52 million in debt and $1.05 million in notes payable and capital leases. Other funds include $1.5 million over five years for infrastructure and health care services, $1.4 million in operational capital, a $1.2 million “transfer MRI” and a $1.01 million upgrade to the IT and electronic medical-records system.

The proposal also states the intention to maintain all current employees who meet KRH’s hiring protocol.

Ward VanWichen, CEO of Marias Medical Center, says KRH has been providing rural health care assistance along the Hi-Line for decades, and recalls the relationship in the late 1990s when he worked at Northern Rockies Medical Center in Cut Bank. He said the current deal upon finalization would bolster Marias Medical Center’s “efficiencies, effectiveness and economies of scale,” including access to expertise and capital.

“It keeps health care local, it sustains us, it helps us move progressively into the future in different ways that we might not have been able to do as a standalone,” he said. “I think we’re all very excited about this opportunity.”

In the big picture, Rasmussen noted that KRH’s partnerships with rural health care providers isn’t unique, citing as an example the Billings Clinic system, which has affiliates across Eastern Montana. He said those relationships give rural hospitals access to new capital, expanded capability to improve aging infrastructure, more highly specialized services, and various other benefits.

“It’s becoming more and more difficult for small critical-access hospitals to survive without some level of partnership with somebody else,” he said, adding: “What’s taking place across the Hi-Line is a big brother or big sister is stepping in to help them grow and respond to their communities.”

Uncertain Fall and Winter

Last week, Rasmussen said stakeholders held a call to develop a plan for the state’s response to the forthcoming influenza season. This is normally the time of year that public-health departments and hospitals discuss how they will roll out the flu vaccine, but the atmosphere is muddied by questions over testing and resources. Rasmussen noted that flu-test manufacturers have shifted resources to COVID-19.

“We’re having that conversation in the middle of a pandemic for which a lot of the testing resources are being taxed,” he said.

Moreover, there would be health-care consequences if suddenly this fall there’s a surge in people requesting COVID tests because they are experiencing symptoms that are also associated with flu and common colds. Hospital bed capacity and PPE availability are additional concerns.

“If we have a very tough flu season, our beds are going to be filled with flu patients, and then there are COVID patients and emergency patients, and you’re trying to figure out how to do elective procedures,” Rasmussen said.

The convergence of flu season and COVID-19 also weighs on Dr. Nelson’s mind at KRH.

“I’ll admit I am concerned about that,” Nelson said. “Unless we’re able to get a hold of that epidemic from a public-health perspective, I’m concerned about the flu patients and having that many patients with symptoms very similar to COVID-19 and requiring testing or isolation.”

On the flipside, the precautions that have become habit for many people during COVID-19 — hand hygiene, staying home when sick, social distancing — also help prevent influenza and colds.

“We can decrease the overall burden of illness just by doing these measures,” he said.

Perhaps most critical of all, Nelson said, is widespread mask wearing, whose effectiveness has been “demonstrated repeatedly in countries across the world.”

“I think it’s absolutely, absolutely, absolutely important that people wear masks,” he said. “It’s really the best method we have to reduce transmission between people, which is how (COVID-19) spreads.”

Nelson is confident that whatever the next few months bring, the KRH workforce is capable and ready, as it has been throughout the pandemic.

“I’m so proud of the entire staff, our physicians, our nursing staff, our other staff, everyone has just stepped up to do the right thing to take care of patients. I couldn’t be prouder,” he said, adding: “This is stressful. It’s stressful for all of us to have social distancing in our lives, and it’s particularly stressful for health care workers. They’re on the front lines of trying to keep people healthy.”