A faint “yip yip yip” punctuates the quiet winter air like the sound of a radio in another room. I scan the snowy road and watch expectantly at the nearest turn for a glimpse of the Schurke family and their sled dogs.

The volume goes up, followed by an explosion of snow, white fur, pink tongues and flying paws. This arrival plays like a movie, with the beautiful dog sled team erupting from a wintry Mission Mountain landscape plastered against cobalt skies. It’s a breathtaking sight. The sled slows at the “whoa” command and then stops. Mark, Samantha and their sons, Otto and Dietrich, greet me with smiles.

It’s a perfect day for what is, surprisingly, a rare outing for the Schurke family — “kind of like the shoemaker whose kids have no shoes,” Mark says with a laugh. Winter is busy for Base Camp Bigfork because of the popularity of their dog sled excursions.

Mark says it’s a bucket-list goal for people to have a hands-on experience mushing a team of the rare and enchanting Canadian Inuit dogs, the original sled dog of the high Arctic and last remaining aboriginal dog of the Americas. These dogs have an insatiable appetite for pulling and can transport at least twice their weight in payload.

As we lounge in the potent March sun, the dogs engage in “conversation” with one another, ranging from a gentle nuzzle to the baring of teeth and startling bursts of growls — a display of the tug-of-war in establishing pack hierarchy, similar to that of their ancestor wolf. Shortly afterward, the entire team is sprawled out amicably napping in the snow. Mark tips the sled on its side as a makeshift bench, and the Schurkes huddle together for a cup of warm cider.

It all began 20 years ago when Mark was introduced to this unique breed, also known as the Eskimo dog, when he did an internship with his uncle, Paul Schurke of Wintergreen Dog Sled Lodge in Ely, Minnesota. Paul is known internationally for his sled dogs and arctic explorations. Mark became fascinated with the Canadian Inuit dog, whose double coat, tough athletic build and passion for pulling made them essential to the Inuit people dating back 4,000 years for hunting, navigating and surviving in the harsh Arctic climate. The dogs also made it possible for explorers to reach the North and South Polar regions.

A changing economy and culture included the introduction of the snowmobile in the late 1960s, which replaced the dog sled as transportation and threatened the future of the Inuit dog. Estimated populations of more than 20,000 dogs dwindled to 250 when the dogs fell into disuse and were killed or died from disease. A small group of people jumped in to save the breed, and there are an estimated 500 dogs today.

Paul Schurke owns the nation’s oldest sled dog center with 65 dogs, which is thought to be the largest working kennel of Canadian Inuit dogs in the world. Mark felt fortunate to have him as his mentor and remained at Wintergreen Lodge as kennel manager and a guide for several seasons. He fell in love with the dogs and living on the edge of wilderness.

“I felt as if I was at the beginning of the story,” Mark said. “It was eye opening.”

This experience led to a move to the Bigfork area with his wife Samantha where they established Base Camp Bigfork in 2008 to share their love of outdoor adventure. Even though dog sledding is at the heart of their business, they operate year-round offering lodging, guided outings and summer and winter gear rentals.

Mark notes that the relationship with a working sled dog is different than that of a pet. Base Camp dogs live outside in an open kennel with large pens to allow them to live the pack life that is in their blood. A thick forest surrounding the kennel area helps blend the chain link fence and dog yard into the environment. Wooden signs bear the names of the dogs and a wall serves as a sort of dog hall of fame for retired or deceased dogs. Litters sometimes carry a theme such as Kapow, Zap and Smash, and others bear Inuit names such as Anernek, Pitsiak, Tukpiq, Unama, Toyuk, Sus, and Suka.

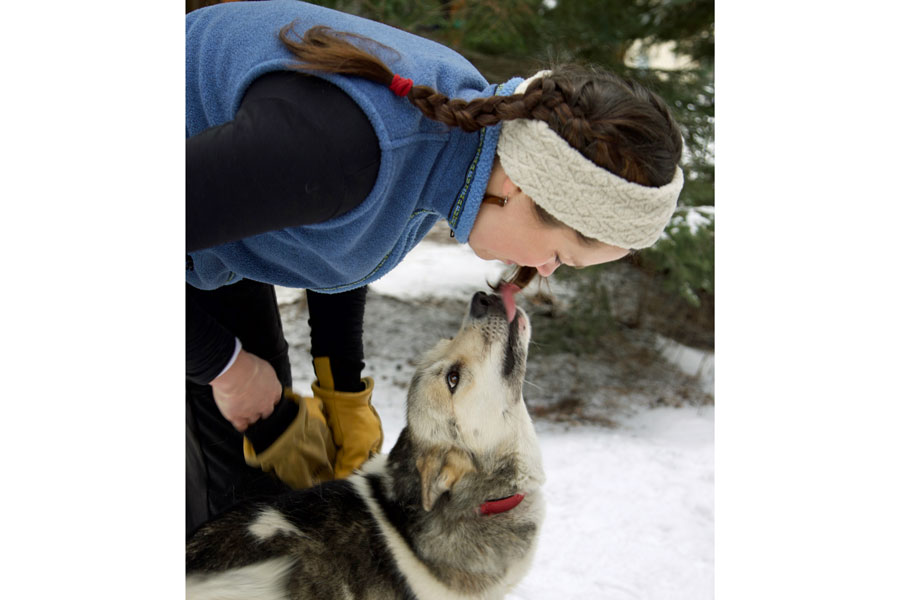

Each of the dogs has its own personality, which is considered in their placement in dog sledding. Although intense, they are also personable and affectionate. Mark encourages interaction, which can include harnessing and caring for the team as a part of the experience, but because of their size, strength and excitability, he monitors human interactions with the dogs.

The regal dogs are characterized by a broad chest, muscular legs, pointy ears, wedge-shaped heads and bushy tails that curl over their backs. The hardy breed has been naturally selected by the harsh Arctic climate, and healthily work as sled dogs nearly to the end of their lives.

When released from the pen, the dogs race around with excitement but fall into a calm compliance when it’s their turn to be harnessed and clipped into the tug line. Pulling is so instinctive that the Inuit dogs require little training or encouragement when hooked up to the sled. Control of the tremendous dog power is maintained by voice commands, a brake, shifting of body position and a pedal kick when needed (for instance in deep snow or going uphill).

Mark dons his cross-country skis to guide the dogs and be close to the sled to intervene if needed. This allows guests to experience the thrill of mushing in a safe and secure way.

The romance and beauty of their dogs and sledding have been captured in a number of films, television shows and advertising photo shoots, including a Warren Miller film, a documentary and two Montana Office of Tourism commercials.

Mark has become an expert in the niche world of Inuit dogs.

“I have a unique relationship not many have experienced,” he said. “It is such an honor to be involved in preserving the dog and the dog sled experience.”

That is much of his motivation in offering recreational dog sledding to others.

But today is reserved for the Schurke family. Mark throws back the last of his cider and the family packs up. The dogs spring up from their snowy bed ready to go. Mark sprints ahead of the sled on skis, after which the dogs are allowed to follow.

It’s a glorious day for the Schurke family and, of course, for the dogs. After thousands of years, this is still what Inuit dogs love to do. I hear, “hup hup, good dogs,” as they disappear into the sun and around the next bend.

Editor’s Note: This story appears in the winter edition of the Beacon’s quarterly magazine Flathead Living, on the newsstands across the valley.