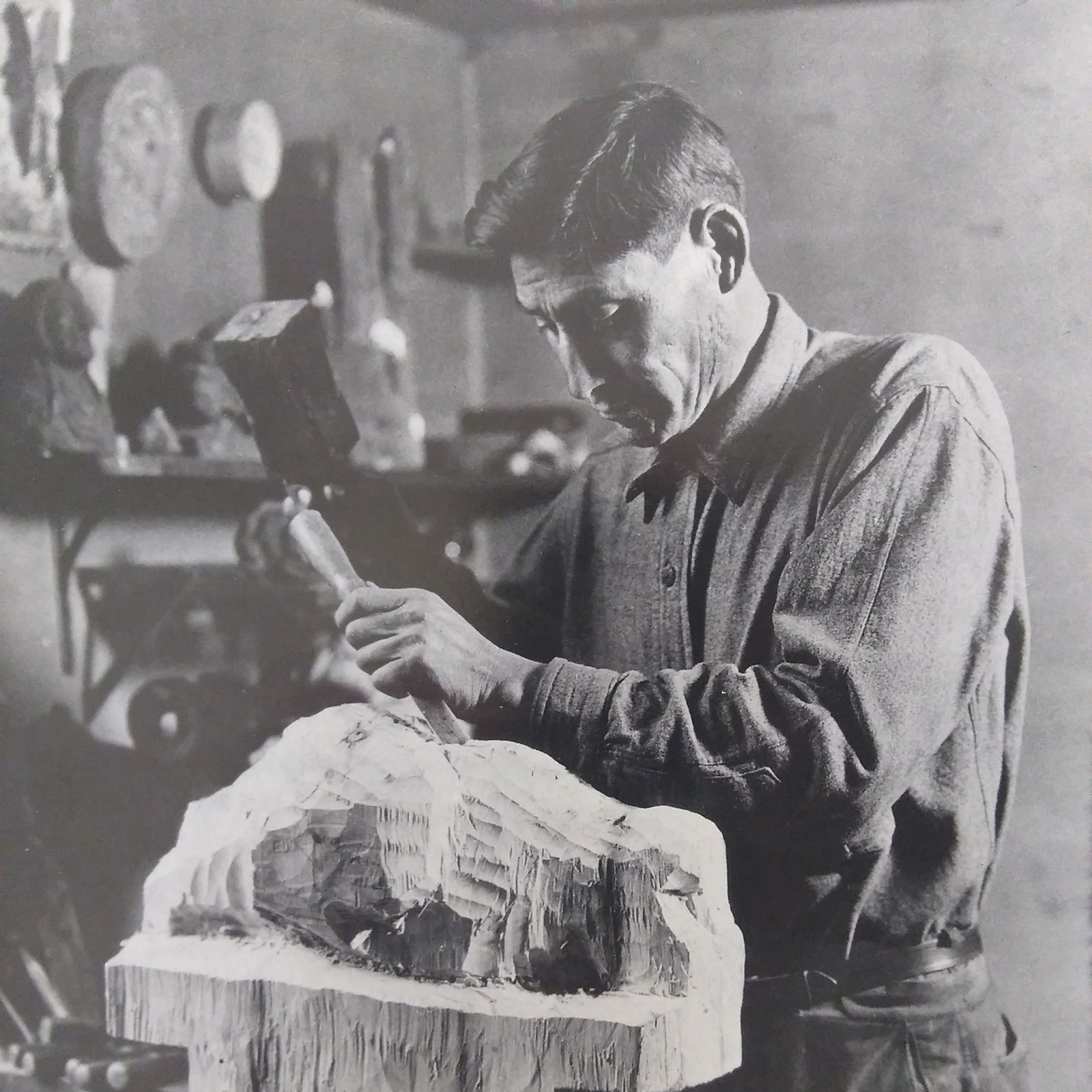

Acarver of craggy animals, his stony, weather-beaten face practically seemed engraved, too. His lined hands, flowing with fluency, were hearty and coarse like oak or boulder, and no less substantial.

He had been robbed of the ability to speak or hear, yet his was a life without margins. By way of nimble fingers and fixed eyes, he felt the urge of the senses, scrounging ordinary wood that he hewed and chipped deeply, lovingly, with the characteristics of his own spirit and that of his subject matters.

Indeed, John Louis Clarke’s physical deficiencies did not handicap his eloquence in sculpting or painting. Perhaps, conversely, something about that silence bestowed him with an indomitable outlet for his interior emotions, a conduit which speech might not have ever been able to adequately or wholly express.

Learning the Language of Art

The son of Horace and Margaret Clarke, John Clarke was born into history near Highwood, about 25 miles east of Great Falls, in 1881. Sources vary as to his exact birthdate, but Clarke himself listed March 23, 1881 in a letter written in 1964.

His father, Horace John Clarke, was half Blackfeet, the son of Malcolm Clarke, a classmate and friend of Civil War General William Tecumseh Sherman.

According to a biographer of the Clarke family, Malcolm Clarke was a famous pioneer fur trader who “bought a toll road between Prickly Pear Canyon and Helena, headquartering at the north end of the canyon, that had been chartered by the first territorial legislature.”

Malcolm, a member of the American Fur Trading Company, was “adopted into the Blackfeet tribe,” but after the company’s relationship with the Blackfeet turned increasingly unstable, he “was later killed in a horse stealing raid, near Helena by Indians.” Malcolm was purportedly killed by Mountain Chief’s son, and in the attack, Horace, John’s father, was left for dead.

John’s mother, Margaret, was “a full-blooded Blackfeet,” known as First Kill, the daughter of Blackfeet Chief Stands Alone. First Kill, who was born in 1849 and died in 1940, married Horace Clarke in about 1876.

When John was 2, he was afflicted with deafness, most likely the result of a near fatal bout of scarlet fever. Because of this, he never learned language. Despite this trauma, or because of it, Clarke developed strong artistic proclivities, fashioning clay animals that he would present as gifts to his relatives. Struck by the uncanny likenesses of these creations, Margaret encouraged her son to amble the mud banks near his home to gather more clay. She also instructed him to be quick to observe wildlife, but methodical in examining it, instilling in the boy a sense of accuracy in shape and form not teachable in art schools or in books. Perhaps, even then, Margaret recognized that art would be Clarke’s source of understanding and compassion, his refuge.

Clarke lived in Highwood until he was 7, when his father sold the family ranch. Around this time, his family members and elders, recognizing the permanence of the young boy’s lack of communication, named him Ca-ta-pu-ie, meaning Man-Who-Talks-Not. The same year the family moved to the Sweet Grass Hills, where his father “cultivated sheep and mining interests.”

Taught to read and write at Fort Shaw Indian School, Clarke was sent to a series of schools for the deaf, including periods at the North Dakota School for the Deaf at Devil’s Elbow from 1894 to 1897 and the Montana School for the Deaf and Blind at Boulder (the school is now at Great Falls) from 1898 to 1899. At one such school, St. John’s School for the Deaf in Milwaukee, Wisconsin, Clarke was introduced to woodcarving through a vocational training course in furniture decoration. During the course, it was said that he excelled in altar carving. He must have impressed somebody in Milwaukee with his ability because he was asked to carve church alters in that city.

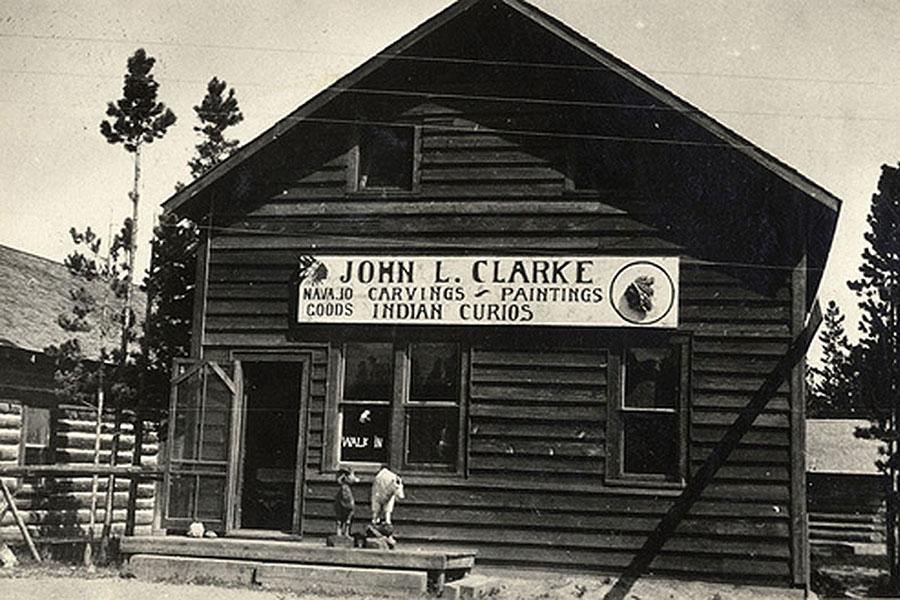

East Glacier Studio

The Clarke family eventually moved to the community of Midvale, most likely in 1913, which later became East Glacier, “where they had a land grant north of the Great Northern Railway tracks and where the Glacier Park Hotel now stands,” according to one account of the area’s history.

The mass and extent of the fledgling park — it was established as America’s 10th national park just three years earlier, in May 1910 — was a great benefit to John Clarke, providing the backdrop of observation and inspiration to live his art wholeheartedly. It would not have been unusual to see Clarke hunting or fishing or traveling around East Glacier in his Jeep on the search for burls, weather-beaten roots and twisted pieces of lakeshore wood.

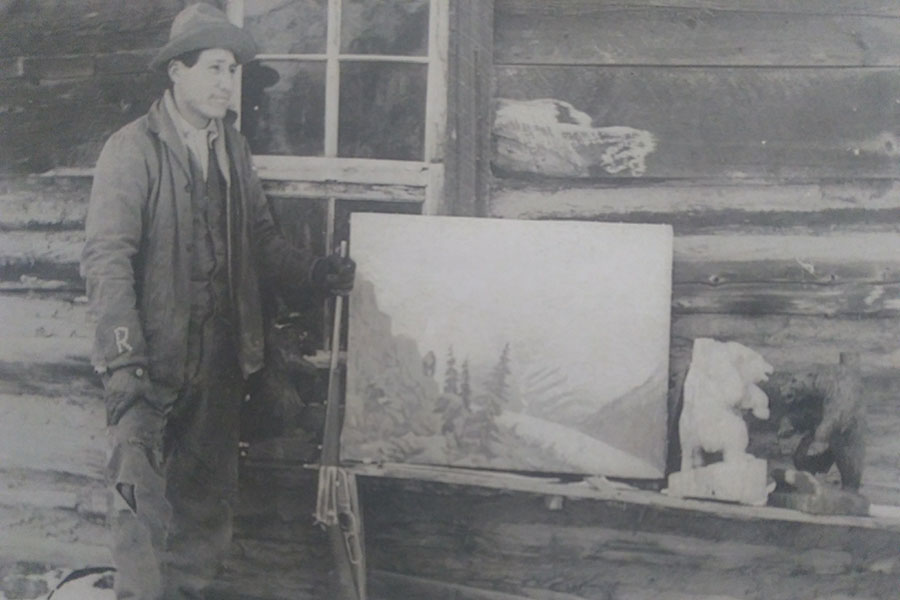

Clarke’s studio was a scene from the animal kingdom, from bears to horses, to buffalo and mountain goats. Soft, spongy cottonwood, though difficult to carve, was his favored medium of wood; its suppleness allowed Clarke to rough the fibers into realistically shaggy animal fur. He commonly used heavy bark, cedar, walnut and maple, too. Not limited to carving, Clarke also addressed the world in crayon and painted in oil.

Clarke worked through the long winters under the sway of the park’s soothing, yet severe, beauty. Living simply with few possessions, he kept his body healthy. Under the golden thaw of sunshine, he would exhibit his art outside, in full display of the tourists who often lined the perimeter of the small studio. With dark eyes peering through his glasses, he would chisel for them a reproduction of his favorite puppy, from the trunk of a tree that he had chopped down on the mountainside.

Lamp carvings on desks in the big hotels and the little animals for sale in their novelty shops would have been identifiable to locals as Clarke’s work. His first exhibition outside of the area was held in Helena in 1916. Among the pieces exhibited was a bison bull and cow, which through a long string of events commanded the attention of someone associated with an esteemed sculpture school in New York. According to a 1933 edition of True West, “Critics, artists and gallery conductors from the east came to the park, saw what he was doing and encouraged him.”

His reputation as a sculptor accrued due to his ability to depict the animals of the wild with realistic accuracy. He traveled around to work at fairs and made his living solely from his art, selling pieces that ranged from five to five hundred dollars.

Though unable to correspond through sound — “deaf and dumb,” “deaf Indian” or “deaf and mute” are written descriptions that commonly prefaced the artist — Clarke was very responsive to people, communicating with the same pencils and pads that he used for sketching.

“John liked people very much, and they liked him,” said artist Bob Morgan, in a radio program that aired in February, 1972, about Clarke titled “The Man Who Speaks Not.” “Why, there were people who went back to East Glacier year after year just to see John Clarke. And he had a special way to reply when someone wrote to see when their work would be completed. He would send a post card, on which was sketched the work in its present state. It might show a half finished figure, or even a Jeep heading out over the country to take the artist where he could observe wildlife.”

A Revered Sculptor

Clarke was considered a great sculptor because of his aforementioned keen perception of wildlife, his long hours of observation of the animals in their true habitat, his superior anatomical precision, and his meticulous practice in depicting them in their natural poses. “His figures are correct to the finest detail and his work, like that of western artists, is a definite contribution to posterity,” trumpeted the Great Falls Tribune in 1932.

Indeed, President Warren G. Harding owned an eagle holding an American flag carved by Clarke, which was displayed in the White House. Business magnate John D. Rockefeller purchased four of his carvings in 1924 alone. A visit from Charles M. Russell (1864-1926) to Clarke’s studio was an annual summer occurrence for many years, until ill health made it impossible for the prestigious landscape and bronze artist to visit. According to a newsletter published by the Montana School for the Deaf and the Blind in 1927, Russell’s arrival “gave the deaf mute new vision, for there was always friendly, helpful criticisms,” while courage was “born anew” in Clarke’s heart “for Russell never overlooked good points nor forgot to mention them.”

In 1918, Clarke married a woman named Mary Peters and they adopted a daughter, Joyce, in 1931. The family lived in the back of his studio. A writer from the Glacier Reporter described Clarke’s home and studio as “old and decrepit.”

“John sits on the front porch on the warmer days smoking his pipe and gazing at the Rocky Mountains in the distance,” according to the Glacier Reporter story. “The porch is laden with twisted and gnarled tree stumps and branches which the old Indian carves into beautiful mountain settings.”

In 1940, Clarke was commissioned to deliver two relief panels in wood for the entrance to the Museum of the Plains Indians and Crafts Center in Browning. It’s difficult to say how many pieces he completed in his lifetime and how many of them have endured. It has been written that Clarke’s works number in the thousands, but no official tally or log has even been conducted.

Nevertheless, late in his eighth decade, he could still be found many hours a day hunched over his work bench in his cabin, whittling bears and mountain goats, his graying hair flopped and split on his deeply etched forehead while his ripened, muscular hands maneuvered back and forth with the carving tools. When not immersed in art, he could be found “beautifully seated, peaceful and smiling,” according to the recollection of one visitor.

Working up until his death, Clarke’s final months were punctuated by moments of extreme physical discomfort: almost blind, his eyes were so clouded with cataracts that he was unable to discern much beyond indistinct silhouettes. His final known production — a carving of a large grizzly springing itself out of a bear trap — was carried out with the primal touch of awareness and harmony.

Pronounced dead at 4:30 a.m. on November 20, 1970, in Cut Bank Memorial Hospital at age 89, John Louis Clarke was laid to rest in East Glacier Cemetery, in his beloved Glacier National Park.

While his studio was demolished years ago, his work lived on at the John L. Clarke Western Art Gallery & Memorial Museum, established in 1977 in East Glacier, where his art continues to articulate the essence of his voice.