Tina Buckingham was excited.

It had only been a few years since she moved west from Boston to raise a family in Montana, and now her career in show business was following her as well. To her delight, young stars in Jeff Bridges and Sam Waterston were filming “Rancho Deluxe” in Livingston, and she jumped aboard quickly as a production assistant for the 1975 release. But that wasn’t the project she was excited about.

No, a couple years later, Bridges and Waterston were coming back. And joining them was the hottest new director in Hollywood: Michael Cimino. His second movie, “The Deer Hunter,” won the Academy Award for Best Picture in 1978, and literally the next week Cimino and that movie’s Oscar-winning star, Christopher Walken, were in Kalispell, of all places, to create Cimino’s next masterpiece. The incredible cast for the new movie included Walken, Bridges, Waterston, Kris Kristofferson (the film’s star), John Hurt, Isabelle Huppert, Mickey Rourke and an un-credited Willem Dafoe, in his first movie.

Buckingham had to be a part of it. So she drove to Kalispell, popped into the one hotel big enough and luxurious enough to accommodate the Hollywood elite, and wasn’t going to take “no” for an answer.

After being rebuffed initially at the Outlaw’s front desk, she worked her way onto the ostensibly closed set, convinced an assistant director to give her a shot, and landed a role as an extra in what was shaping up to be one of the biggest, boldest and most expensive film productions of all time.

She was going to be in “Heaven’s Gate.”

As it turned out, the fact that Tina Buckingham does not actually appear in “Heaven’s Gate” is an almost too on-the-nose illustration of the excess that doomed the movie’s production. The stories of “Heaven’s Gate” have been well documented and are so numerous that an entire book was written about it, Steven Bach’s “Final Cut: Art, Money, and Ego in the Making of Heaven’s Gate, the Film that Sunk United Artists.”

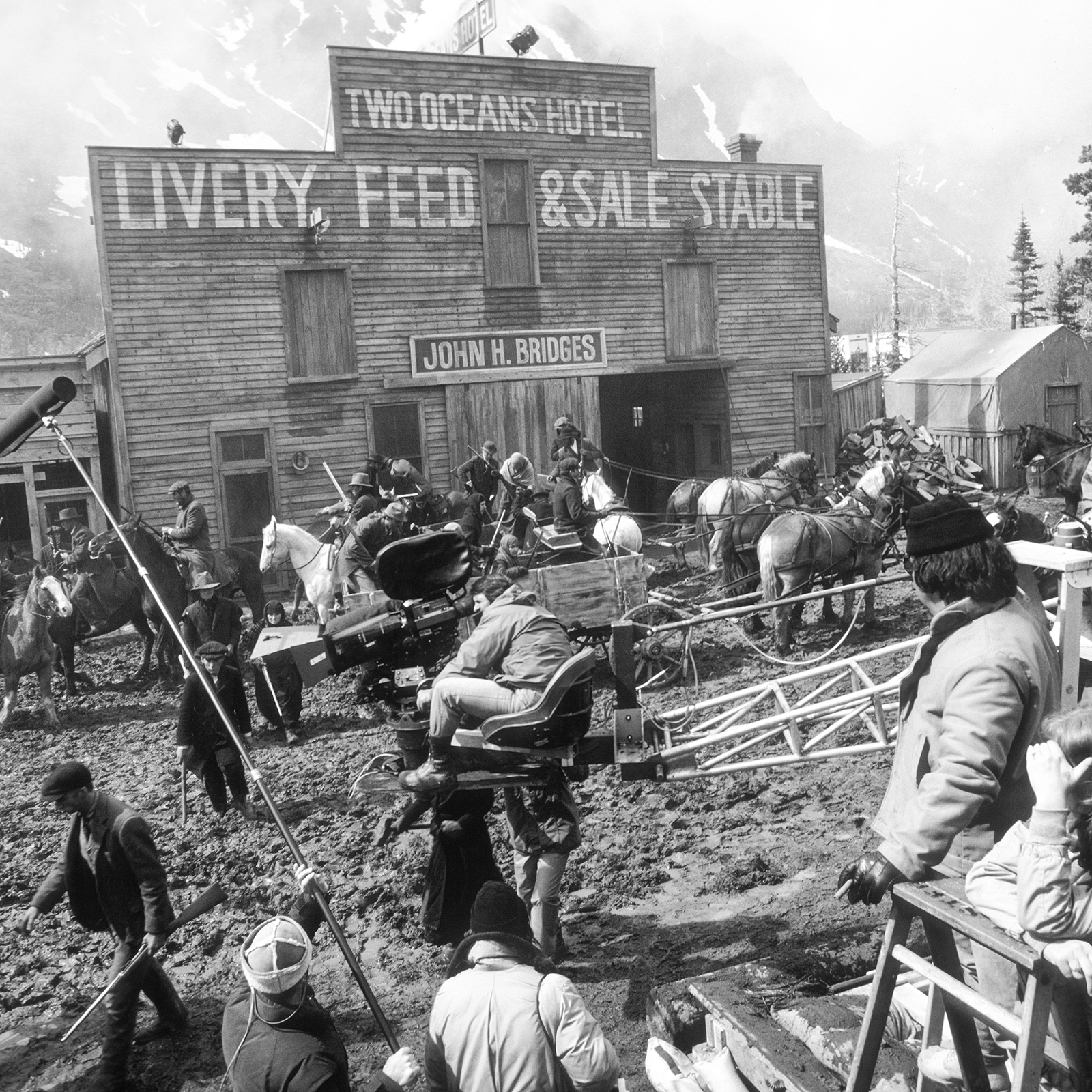

The movie, which Cimino also wrote, chronicled the Johnson County Wars of 1890 when Wyoming ranchers fought European immigrants moving to the area, but the plot is the least enduring part of the movie’s legacy. The production was an exercise in excess, bloating from an already ambitious initial cost of nearly $12 million to a final budget of $44 million, and upon its release it grossed less than 10 percent of that.

Garry Wunderwald, the director of the Montana Film Office from 1977-90, was in charge of bringing major motion pictures to Montana, and he pulled out all the stops to court Cimino. He helped the director buy two new Jeeps, rented a fleet of two dozen Chevrolets, convinced the National Park Service to approve filming in Glacier National Park, found a $5,000 chrome-plated, pot-bellied stove for a scene in a roller rink, and even located a train depot out of state, in Wallace, Idaho, that better fit Cimino’s vision than the one in Kalispell.

Wunderwald set the crew up at the Outlaw Inn, and the nine-month production would call the hotel home almost the entire time, renting a nearby warehouse to store the vast wardrobes needed to appease the exacting director. Cimino would build elaborate facilities to make his movie look precisely as he wanted — and run up the tab on its financiers — including a house of ill repute called the Hog Ranch that, after filming was done, Bridges relocated to Livingston and made his Montana home.

As for the shooting itself, much was done in the area near Two Medicine Lake, and since it and Kalispell are easily two hours apart, every day’s work began extremely early for Bridges and extras like Buckingham, who spent three months working on the movie in the spring and summer of 1979. Buckingham would rise at 3 a.m. every morning, five days a week, during that stretch to begin her day.

“We get (to Two Medicine) and it’s still dark,” she recalled. “We get off the bus and we eat breakfast and got back on the bus and waited for our call. We went for our placements, still in the dark, because obviously directors love that sunrise shot and we would do sunrise to sunset, truck back around the park, take off our wardrobe and do it all over again.”

The conditions were no easier on the film’s stars.

“I remember we would all get in vans, early in the morning, about 5 o’clock in the morning, take a two-hour drive out to location, to the battlefields,” Bridges said in an interview. “That was quite an adventure, going long distances on dirt roads. I remember sleeping on the floorboards and inhaling all that dust going to and from work.”

When the movie was finally finished, Cimino presented a five-hour-plus epic to executives. They trimmed it to a more palatable 219 minutes for its debut in November 1980, but after critics reacted in horror, it was re-released in April 1981 at nearly two and a half hours. The reception wasn’t much better.

“I saw the long version of the film in New York back in November and it was pretty much of a mess,” the late critic Gene Siskel remarked on “Sneak Previews,” the TV show he hosted with Roger Ebert. “Now, however, the film’s been cut by 40 percent. It runs two hours and 18 minutes and it’s still a turkey.”

Buckingham had a different experience the first time she saw the movie. She went to a nearby theater, excited to get a look at herself in action and at the meticulously detailed and stunningly beautiful scenery — the one nice thing most people agree on about the movie.

“I was in close proximity to some of the actors in many scenes,” she remembered with a laugh. “So there I was in the theater — I would go, ‘I was in this one. Here I come, here I come!’ And I was just off-camera, or they cut away from the place where I was.”

Despite her exclusion from the screen, Buckingham still cherishes her experience. Since working on “Heaven’s Gate,” she has enjoyed a long career in the movie industry that has included a job as a location manager for “A River Runs Through It” and casting director for a handful of other productions.

“It was wonderful,” Buckingham said of working on Cimino’s movie. “If I had never gone on, if the movie business had died down, I would have had my 15 minutes.”

Bridges, too, spoke glowingly of his experience, and he believes critics have treated “Heaven’s Gate” unfairly.

“It’s a wonderful movie,” Bridges said. “I remember how disappointed we were when we heard the terrible reviews that movie got, and that really colored people’s viewing experience. Fortunately, the movie still survives and people can enjoy it. My own opinion is that it’s a masterpiece and it really magically puts you back in time.”

That “Heaven’s Gate” became one of Hollywood’s cautionary tales, that it essentially ended Cimino’s career and that it almost single-handedly put the studio that produced it — United Artists — out of business, is no fault of the Outlaw Inn, of course. But it is the movie most synonymous with a roaring era for the now-beleaguered hotel, which once stood as a crown jewel of the Flathead Valley.

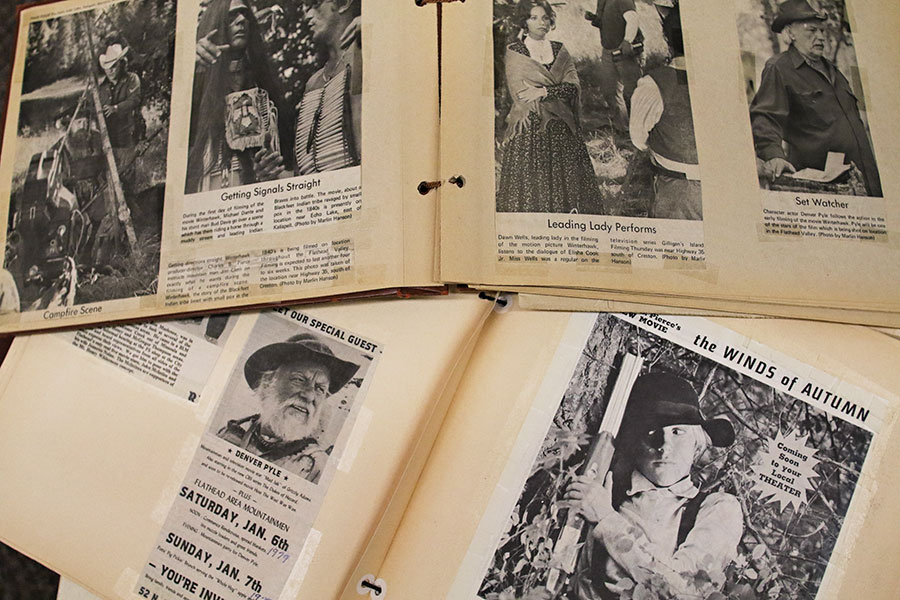

Ron Kelley operated his barber shop, the King’s Lair, out of the Outlaw Inn for decades, and was there in the 1970s, cutting movie stars’ hair, when crews for movies including “Heaven’s Gate,” “Winterhawk,” “Damnation Alley,” “Winds of Autumn” and others set up shop at the Outlaw. Kelley would sometimes even pick up cast members at the airport when they flew into town and bring them down a mostly-empty U.S. Highway 2 toward Kalispell’s downtown.

“There was nothing here; that’s what surprised people,” Kelley remembered. “Of course, we swung down Main Street and now we’re leaving town (headed south) and they started to say, ‘Man, we’re leaving this little village?’ Well, then we round the curve and they finally see that hotel and they gasp.”

The Outlaw, in fact, was one of the reasons films had started coming to Kalispell in the first place. Wunderwald, a third-generation Montanan and professional photographer who had vast knowledge of cities and landscapes throughout the state, would bring dozens of productions to Big Sky country during his 13 years working for the state. When it came to selling a place like Kalispell to Hollywood producers and directors, the Outlaw was part of the pitch.

“Kalispell had accommodations,” Wunderwald said. “The Outlaw Inn was very well-managed, it was fairly new, and (production teams) liked it there because that motel had room. It had parking space. And they wanted entertainment for their crews, (and the Outlaw) had bands there at night and some really nice rooms.”

Buck and Rusty Torstenson opened the Outlaw in 1973, and Kelley remembered the owners immediately seeking to gain the hotel and conference center business from around the world as a luxurious gateway to nearby outdoor recreation.

“The Outlaw looked for things (like movie productions),” Kelley said. “That’s what made the place run — they did not spare money. I can vouch that at one time I saw 23 busses sitting in that lot and they’d come here from everywhere, Australia to Europe.”

Nights at the Outlaw while the movies were in town became the stuff of legends, too. According to “Shot in Montana,” a book by Brian D’Ambrosio, Kristofferson would “jam with his band in the hotel’s lounge when he wasn’t rehearsing scenes” during his work on “Heaven’s Gate,” and movie stars would routinely mingle with locals at the hotel’s adjoining restaurant and bar, Hennessey’s Steak House, usually undisturbed.

“People definitely would hang out at the Outlaw, and they could see Kris Kristofferson and Christopher Walken,” Buckingham said. “And they were totally courteous, totally respectable. That has been my experience in every single movie I have worked on in Montana. (Movie stars) will tell you they feel comfortable here because they can go out in public and not be treated differently than anyone else.”

That’s not to say that every night at the Outlaw was quiet. Michael Dante, an Italian-American who starred in the 1975 film “Winterhawk” as a Blackfeet warrior, was relaxing one night during filming with his co-stars when one of them brought out a bow and arrows used for filming.

“The (Outlaw) was memorable — that was our headquarters and a very fun place. They had great music every night,” Dante said. “When I think of it I think of the night that (actor) Woody Strode … he shot two arrows in the ceiling in the dining area.”

The productions became an obsession of the local media as well. Newspapers breathlessly covered the movements of actors and production teams, traveled to shoot the action on set and interviewed the industry’s key players. The Outlaw even capitalized on the fame, branding itself in one print advertisement as “Home of the Stars.”

The movies made an impact beyond just the hotel, too. Wunderwald aggressively recruited films to Montana and found that most towns, government agencies and local businesses were more than happy to welcome the cash influx that movies brought with them.

“All these film projects were adding to the economy of Montana,” Wunderwald said. “They hired all these people.”

Production companies paid private landowners for use of their property, had local contractors build pieces of their sets, and employed hundreds of other locals in various odd jobs. And beyond that, he said, the retail businesses in town enjoyed a tremendous boost. Dry cleaners were swamped, photo labs developed mountains of negatives, restaurants and bars saw a swell of business, and much more.

“There’s all these other things you do not think about,” Wunderwald said. “The car washes — the guy told me he was going to invest in another car wash just from ‘Heaven’s Gate.’”

In the years after “Heaven’s Gate,” film productions would intermittently come through Kalispell for movies like “Big Eden,” “Beethoven’s 2nd” and “Devil’s Pond.” But the days of major productions taking up residence here disappeared. The Outlaw has gone through several rounds of new ownership in recent decades — it now operates as the FairBridge Inn, Suites and Outlaw Convention Center — and endured a series of blows to its reputation, not the least of which was the conviction of early Outlaw investor Dick Dasen Sr. on prostitution and sexual assault charges during a much publicized trial in 2005.

In 2015, however, director Sarah Adina Smith came to Kalispell to shoot a dark mystery called “Buster’s Mal Heart” about a hotel clerk and a mountain man on the run from law enforcement, a movie that would be released one year later to critical acclaim. The director came to Montana in part because of a grant offered by the Montana Film Office, the same place where Wunderwald once toiled and worked to out-sell other states and countries that offered financial incentives to productions looking for scenic backdrops.

Wunderwald, though, always had a different few aces up his sleeve. Montana had no sales tax, for one, a fact he promoted aggressively to big-spending producers. And Montana also had the people who were eager to help, who would rather pick up a hammer than gawk at a movie star, and a special place that could accommodate even the day’s biggest stars.

Such a place is central to Smith’s “Buster’s Mal Heart” starring newly minted Oscar winner Rami Malek. In the movie, Malek spends a fair bit of time inside a spacious, dimly lit hotel, a place that feels plucked from a bygone era. The place is the Outlaw Inn.