Editor’s Note: This story originally appeared in the summer 2019 edition of Flathead Living.

Montana’s connections to the National Football League are extensive, including a player on the earliest Green Bay Packers team (Butte-born Jack McAuliffe), a player on the first San Francisco 49ers squad of 1964 (running back Earl “Pruney” Parsons, who was born in Helena), one on the first Oakland Raiders team of 1964 (guard Wayne Hawkins, born in Fort Peck) and one of the most dominant offensive linemen of the 1940s (Anaconda-born Francis Cope, who earned all-decade honors as a New York Giant).

We’ve given birth to or sharpened the skills at the college ranks of several Super Bowl participants and even an NFL Player of the Year (defensive end Doug Betters, Miami Dolphins, 1983).

Many of our links are, perhaps not surprisingly, unusual. “Frosty” Peters set a record of seventeen field goals in a college football game, all by dropkicks, when he was a freshman at the University of Montana in 1924, against Billings Poly. Frosty later starred for the University of Illinois and spent time in the NFL.

One of the earliest and most characterful, though largely forgotten, associations between Montana and the NFL is Nick Lassa.

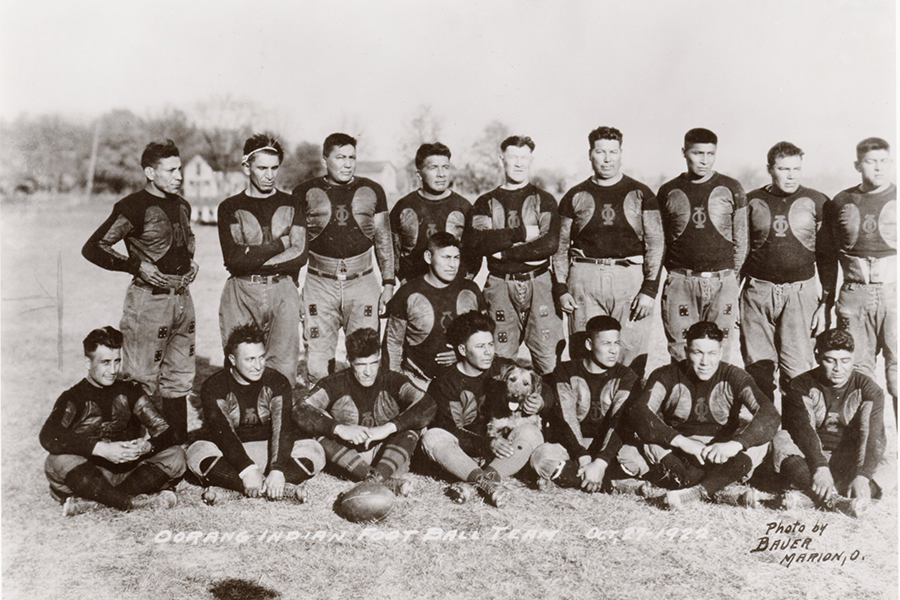

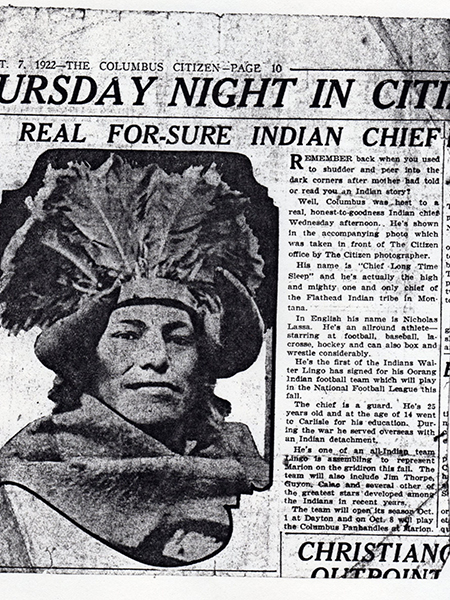

Lassa played as a guard in the NFL in 1922 and 1923 with the Oorang Indians, an all–Native American team based in La Rue, Ohio. Nicknamed “Chief Long Time Sleep,” or “Long Time Sleep,” he was born on July 11, 1898 in the Flathead Valley. A Native American, he was perhaps a member of the Blackfeet tribe, as one newspaper clipping called him “a Blackfoot from Montana.” Other sources propose that he was a Cherokee or a Flathead.

“He’s actually the high and mighty one and only chief of the Flathead Indian tribe in Montana,” reads the September 7, 1922 Columbus Citizen.

Lassa attended and played college football at the Carlisle Indian School and Haskell Indian Nations University. He is said to have been sent to Carlisle at the age of 14 for his education, and “during the war he served overseas with an Indian detachment,” presumably referring to World War I.

The Fort Worth Star-Telegram referenced Lassa in its news brief of the Haskell-Texas Christian game of 1921: “Lassa wore a derby downtown and played football with his hair tied in a topknot with a white cloth.”

In 1921, the Haskell team won five out of nine games scheduled, with a team averaging “scarcely heavier than an ordinary high school aggregation.”

A newspaper clipping from November 1921 refers to Lassa as “a giant guard” and “a 206 pound guard” performing at a weight above the Haskell average, which was slightly above 166 pounds. He was removed from the lineup at the end of the season due to injury.

Somehow he ended up in Ohio as a member of one of the NFL’s original 18 teams. The inventory of inaugural clubs included the Chicago Bears, the Green Bay Blues and five teams from the Buckeye State; the Oorang Indians squad lasted two seasons, 1922 (nine games) and 1923 (eleven games), of which Lassa played every game.

Formed by Walter Lingo, owner of Oorang Dog Kennels, to help market and promote a breed of dog known as the Airedale, the Indians team was organized by Jim Thorpe, heralded in his time (and even now by many) as the greatest all-around athlete in the world.

Thorpe, star of the 1912 Olympics, served as the team’s player-coach, earning $500 a week to coach the football team and run the Airedale terrier business. The team lived in makeshift housing at the Airedale kennel. Lingo bought the rights to his pro franchise for $100, “half the price of one of his trained Airedales,” according to his own brochure. During his team’s debut season, he “sold over 15,000 dogs.”

The Indians lacked a home field, traveling to larger cities such as New York, Chicago, Philadelphia and Pittsburgh. Owner Lingo entertained the idea of playing home games, but dismissed the thought “because the area was too rural.”

When the team formed, Lassa was purportedly the first player to arrive in La Rue. The Lima News described Lassa’s unique arrival:

“The squad mascot was a coyote, brought from Montana by Nick Lassa, nicknamed Long Time Sleep because he was so hard to rouse in the morning. Besides practicing football the Indians are running these Airedales at night. When the Airedales start yipping, Jim Thorpe’s hounds start howling, Lassa’s coyote lends his voice and the bears used in training the Airedales start growling, the place sounds like a circus zoo.”

Other surnames or nicknames on the squad included Wrinklemeat, Laughing Gas, Xavier Downwind, Dick Deerslayer, Baptist Thunder, Joe Little Twig and Bear Behind the Woodchuck. The players were reported to have originated from several different tribes, including Cherokee, Mohawk, Chippewa, Blackfeet, Winnebago, Mission, Caddo, Sac and Fox, Seneca, and Penobscot.

The Oorang Indians played their first NFL game on October 1, 1922, a contest with the Dayton Triangles at Triangle Park. According to newspaper reports, “tickets were $1.75 and over 5,000 spectators showed up.” The intermission was chock-full of theatrics, with Lassa and his teammates changing into “Indian garb” and putting on a show in conjunction with the howling Airedales. In addition to “chasing bears and treeing coons, the players threw tomahawks and shot rifles, did Indian dances and re-enacted World War I battle scenes that included Native American scouts and code talkers.” On several occasions, Lassa wrestled a bear as part of a halftime show at one of the Indians’ games.

Lassa was said to have worked on some of the farms in the area owned by Lingo. Anecdotes of a number of residents recall spotting the big, powerful man jogging in his shorts between La Rue and Marion. Years later, one La Rue old-timer shares his memories about “that nice fella” Lassa to an Ohio author researching the history of the Indians team:

“Well, Nick Lassa stood out because he was here for so long. He was a nice fella. He raised a little hell once in awhile. He was just nice to have around. I remember going to a county fair with him once and you’d have these fellas that had a wrestling ring and they usually had an older wrestler with him. Nick would wrestle this poor sap and win some money. Sometimes he’d win $50.00.”

Oorang played not only football but baseball and basketball as well, while Lassa also boxed and is said to have excelled in lacrosse and hockey. In a March 5, 1920 Kansas newspaper, Lassa is referred to as “heavyweight wrestling champion at Haskell and a member of the R.O.T.C. team.” Indeed, Lassa’s two favorite pastimes in fact appear to be wrestling and “raising hell,” or sometimes both at the very same time.

“Lassa would usually win between 10-20 dollars per match and that money would allow the whole team to go out partying all night,” according to one account, before adding: “The chief, when the spirits have put him in the proper mood sometimes puts on the Tribal ghost dance or the Snake dance, according to the way the spirits have worked.”

After the team folded in 1923, Lassa stayed near LaRue, earning his living as “a professional wrestler and a circus strongman,” and he continued working for Lingo and several other farmers. An Ohio newspaper from December 27, 1927, shows a photo of Lassa and Thorpe, as well as two members of the “World Famous Indians” basketball team in advance of their contest with the Isaly Dairies on the floor.

“Chief Long Time Sleep is a Flathead. That is an Indian tribe and is spelled with a capital f. The chief is 41, the last in a long line of medicine men, being the direct descendant of old Chief Ki-Ki-Che. The chief therefore should get class A rating in any list of first families.”

While his teammates dispersed to many different communities, mostly in Ohio, and started an assortment of careers — one was a police officer, another operated a printing press — Lassa is said to have left the area in the early 1930s. He reportedly halted his rowdy lifestyle, quit drinking, raised a family, “and became a respected member of his community.”

Nick Lassa died in Missoula on September 4, 1964.