When L. Ron Hubbard, the founder of the Church of Scientology, died on January 24, 1986, mystery encircled his death just as it had cloaked the final decades of his life.

Hubbard started Scientology in the early 1950s as a program of spiritual ideas called Dianetics. The advent of the Dianetics theory appeared in The Explorers Journal, with members and associates of the Explorers Club the first to examine his official description of it. Hubbard’s religiosity and grand exploration were both byproducts of traveling to so many far-flung lands through a greater quest for answers to be developed in Scientology, which was significantly influenced by a number of decisive years spent in western Montana.

Hubbard was born on March 13, 1911, in Tilden, Nebraska. After moving from his birthplace, he spent his first two years in Durant, Oklahoma, where his grandfather Lafayette Waterbury had established a horse ranch. His grandfather, known as Lafe, was described as “a big buff man, hail fellow well met, friend to all the world,” according to the Hubbard biography Bare-Faced Messiah. Lafe and his wife produced a son and six daughters, including Hubbard’s mother Ledora May. His father, Harry Ross Hubbard, served in the United States Navy during Hubbard’s early years.

When his father returned from service, the Hubbard-Waterbury family moved to Kalispell, where Hubbard’s grandfather acquired several dozen acres of land for the breeding of blooded mustangs and owned several “famous studs.” His father worked at a local newspaper. It was also in Kalispell that Hubbard said, at just 3 and half years old, he learned to read, write and ride a range bronco named Nancy Hanks, he recalled in the biography Master Mariner: At the Helm Across Seven Sees, “with a single snaffle bit, no quirt, no spurs and a cut down McClellan cavalry saddle, the skirts of which had to be amputated so as to get the doghouse stirrups high enough for me to reach them.” He claimed that he had photos to prove that he was writing well at such a young age. The story that Hubbard retold was one of “an early bond of friendship” formed in the fall of 1914 as the young man danced to the beat of Indian drums and impressed Blackfeet Indians at a tribal ceremony held on the outskirts of town. (Several critics later writing exposes of Scientology dismissed his tale as fanciful and “pure fiction.”)

“I lived in the typical West with its do-and-dare attitudes, its wry humor, cowboy pranks and make nothing of the worst and most dangerous,” he said in Master Mariner. “The weather of Montana is of course brutal. The country is immense and swallows men up rather easily hence they have to live bigger than life to survive. There were still Indians around living in forlorn and isolated tepees, the defeated race, making beautifully threaded buckskin gauntlets and other foofaraw. Notable amongst them was an Indian called “Old Tom” who was sufficiently dirty and outlaw and interesting, a full-fledged Blackfoot medicine man, to be a small boy’s dream.”

Hubbard moved one year later with his family to “The Old Homestead,” outside of Helena. In some of his biographical notes, he wrote, “I grew up with old frontiersmen, cowboys, and had an Indian medicine man as one of my best friends. Until I was 10 I lived the hard life of the West … in a land of 40-degree-below blizzards and vast spaces.” He later spoke of his first real home, “Old Brick,” a property that stood at the corner of Fifth Avenue and Beattie Street in Helena. It served as the home for the entire Hubbard-Waterbury family, including grandparents, Hubbard and his six sisters, Harry Ross, Ledora and a feisty bull terrier named Liberty Bill.

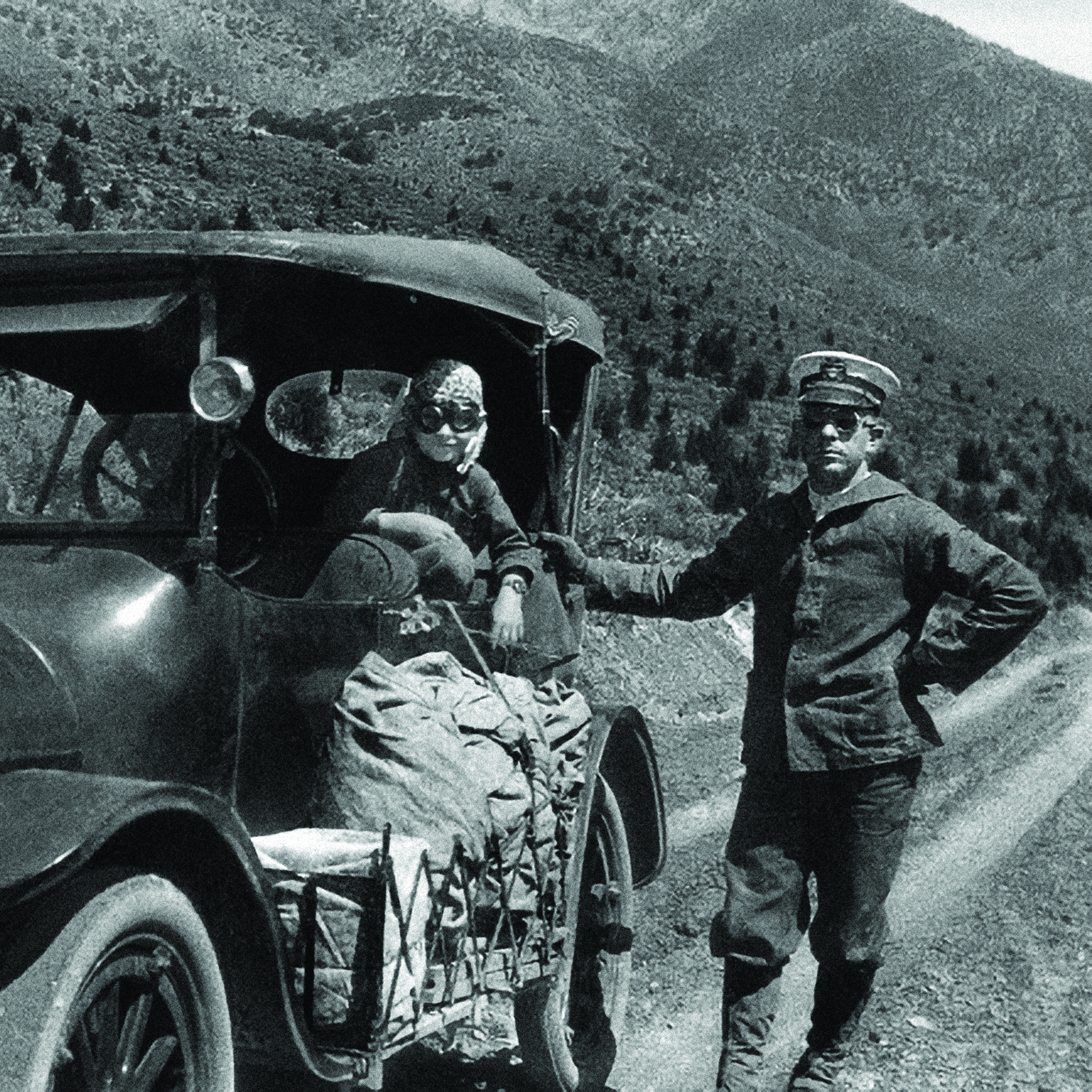

He became a world traveler at the age of 10, thanks to his father’s Navy career, and began his writing discipline by keeping a diary of his travels. After Ross was promoted to lieutenant in the Navy in 1921, the Hubbards embarked on a life of constant movement, relocating almost yearly to posts in Guam, San Diego, Seattle and Bremerton in the state of Washington, and Washington, D.C.

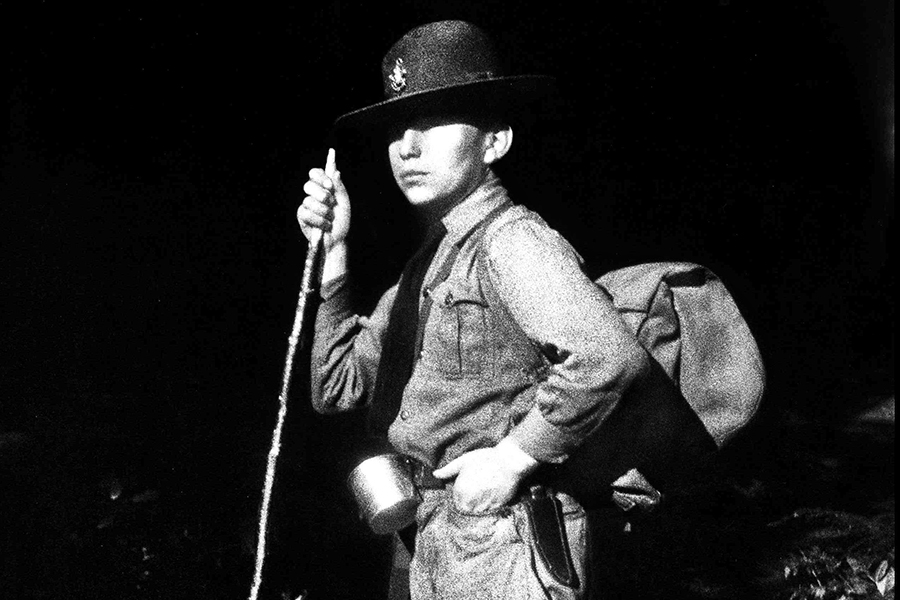

Hubbard always returned to Helena in those early years and attended Helena High School in 1927-28, where he wrote for the school newspaper. He regarded Helena fondly as his “hometown,” according to his early journals, and recounted some of his adventures in a piece in the Helena Daily Independent in 1927. One of the highlights of his travels was witnessing an execution in China, according to the article. He also noted that he had the “distinction of being the only boy in the country to secure an Eagle Scout badge at the age of 12 years,” which he did while in Washington, D.C. The 1928 Helena High School yearbook has a photo of the staff of the bi-monthly school paper, “The Nugget,” including thickly red-haired Ronald Hubbard, one of two “joke editors.” His friends called him “Brick.”

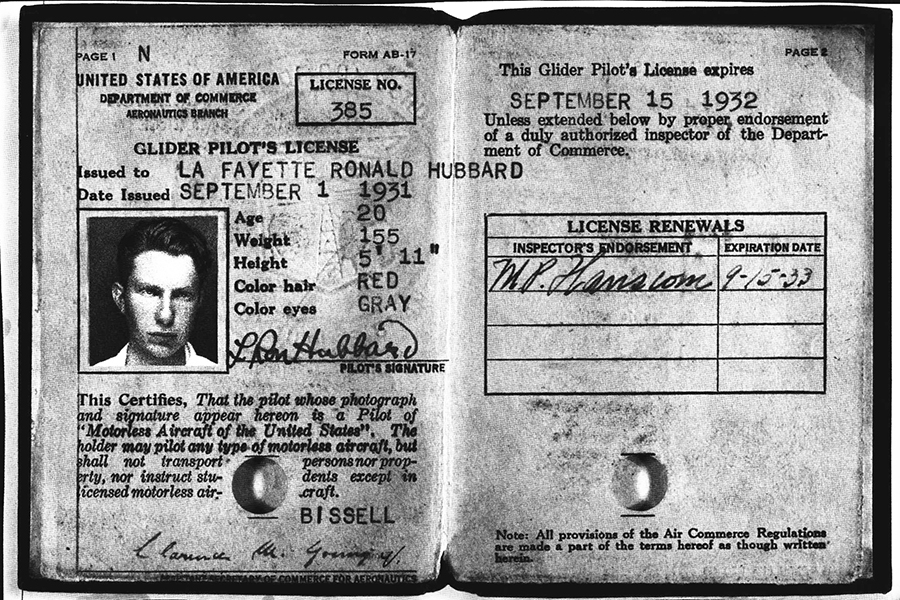

Years later, Hubbard dropped out of George Washington University in 1932 and tried his luck at freelance journalism but soon quit in favor of pulp fiction writing. Most pulp fiction writers told exaggerated tales: mass-market, action-packed stories published in cheaply produced magazines. Dianetics was pitched and written as science fiction, but by the summer of 1950, Dianetics was making its advance up the best-seller lists, and by August 1950, more than 500 “Dianetics clubs” had sprung up across the nation. “A new cult is smoldering across the U.S. underbrush,” declared Time magazine on July 24, 1950.

The wandering spirit of Hubbard’s childhood in Montana stimulated a lifelong love for adventure, and according to Vaughan Young, author of a Hubbard biography, Hubbard attributed his success partly to the “rough and tough atmosphere” of Kalispell and Helena ranch life. He was a dreamer who saw himself as the hero of his own rich adventure story. Considerably less kinder assessments of Hubbard can be located in a number of court records, affidavits and even some of Hubbard’s own early writings, which present the founder of Scientology as a natural-born fabulist whose claims contained many embellishments, joined with, in many instances, out-and-out fabrications.

Hubbard later renamed Dianetics as Scientology, which took hold as a basis of religious beliefs and practices. Two researchers sent on behalf of the Church of Scientology, Pam Schwartz and Mary Pirak, of Hollywood, California, even visited Helena in January 1975 to research Hubbard’s roots and promote their church. There was no Church of Scientology in Montana, they said; the closest were in Salt Lake City and Omaha. (To this day, no church has found its roots in Montana.) Scientology remains a prevalent religion in Hollywood circles today.

Hubbard last visited Montana in 1975 when he and his father came for the funeral of his maternal grandfather. His mother died in 1959. His parents and maternal grandparents are buried in Forestvale Cemetery near Helena. In a profile of Hubbard in The New York Times around that time, the author’s behavior was described as increasingly erratic. While his fortunes had swelled, his friendships had dwindled, almost to the point of his full isolation. He resigned his leadership position in the church in 1966 to devote himself to writing. But he hadn’t been heard from, and even church representatives usually had difficulty pinpointing his whereabouts. A lawsuit by his son to have him declared dead or incompetent was thrown out in July 1975 by a California judge. Hubbard refused to appear at any of the proceedings, and he spent his later years outside the public eye.

Yet, in 1984, two years before his death at age 74, the reclusive science fiction writer opened up one final time to a biographer and recalled how he spent “the most memorable parts of his youth” at Kalispell and “The Old Homestead” outside Helena. He recalled that he never was allowed to ride any of the blooded stock bred by his grandfather, only range broncs and mustangs. “It did not matter how often I was thrown,” he said. “When a mustang exploded under me, goaded on by a frozen saddle blanket, it was I who was always scolded and cautioned not to be mean to the horses. It never seemed to surprise these adults that I remained alive under all this.”

Brian D’Ambrosio lives in Helena, Montana. His most recent book, “Montana Entertainers: Famous and Almost Forgotten,” was released in July 2019.