Editor’s Note: This story originally appeared in the 2020 summer edition of Flathead Living.

Hilary Shaw has come to recognize the particular look of longing that flickers over the faces of longtime Flathead Valley locals — especially the gray-haired, old-school hippie types — when they learn that she works as the executive director of the Abbie Shelter.

“When I meet folks who say they knew Abbie, I can tell these thoughts are swirling: their joy at having a friendship with her, and the grief at her loss,” Shaw, 39, says. “They get a misty look in their eye and a distracted smile.”

Abigail Frederick was a peace activist, an ardent pacifist and a devoted Quaker. She founded the newsletter Peaceweaver to articulate “new patterns of peace in the Flathead Valley.” She was a poet and a potter. Turtles became her totem, her mascot for living in harmony with the earth. With her husband Bruce, she was a parent of two boys: Catnip Echo Ridge and Eli Snowind. In late August 1991, when her boys were 19 and 15, a car struck Abbie as she was bicycling to her home, which was halfway between Whitefish and Columbia Falls. She died of injuries related to the accident. She was 38.

“I often think about the impact in this world that the full force of an Abbie life long-lived might have looked like,” says Kim Sands, 64, of Whitefish, who participated in peer counseling with Abbie. “Always, I sigh with a sense of this imagined loss.”

In 1987, Janet Cahill hired Abbie as the first paid staff member of an organization called the Kalispell Rape Crisis Line. The hotline was almost a decade old, established by a group of “founding mothers” in response to a 1979 national study, which showed that 25 percent of women were experiencing sexual violence in their lifetimes — and that 90 percent of them were taking this secret to the grave. The activists wanted to listen. Abbie also worked at a daycare, and occasionally, when she went to court to advocate for a client of the Line, she had swirls of nail polish decorating not just her nails, but also her hands.

“I knew I wanted her to work for us because of her spirit — she had this warm, kind spirit,” says Cahill, 73, of Evergreen, who was the organization’s executive director for 25 years. “Everyone she talked to, she made them feel safe.”

After Abbie’s death, Cahill says, she honored her lost friend by continuing on with the work. As the community grieved, they redoubled their efforts. Volunteers mobilized to acquire a private facility for sheltering clients — an ambitious goal for the small group — and in 1994, they succeeded. To memorialize their lost comrade, they adopted a new name: the Abigail Frederick Memorial Shelter, or Abbie Shelter for short.

Today, the nonprofit fields about 100 calls per month and serves more than 1,000 people every year. On the 24-hour violence-free helpline, volunteers consult callers who are in abusive relationships, are planning to leave one, or have recently left. Court advocates provide steady support throughout civil and criminal legal processes. An on-staff mental health therapist offers free individual counseling and leads a Tuesday night support group. Educational workshops, presentations and seminars reach thousands of local adults and children. To manage this all, the Abbie Shelter employs seven paid staff members, including one to coordinate a roster of about a dozen volunteers.

The organization is beloved: This past April, when the Whitefish Community Foundation hosted a Day of Giving in response to COVID-19, the Abbie Shelter received more individual gifts, and more dollars overall, than any other participant.

“I feel a deep sense of responsibility for carrying on Abbie’s legacy,” Shaw says. “She was an incredibly vibrant, warm person, and that’s how we want our clients to experience our service … For generations of staffers [of the shelter] to come, they’ll know her without even realizing they do, just because of who we are … She’s just a shimmering spirit all around us.”

Abbie’s friends acknowledge that when people pass away, it’s easy to put them on a pedestal, but, they say, Abbie was really like that. They insist the plain truth is that she was the warmest person you could ever meet. They think of her often, as they grow “Abbie Applesauce” trees in their yards, when they wear turtle-shaped earrings, and every night while setting their supper tables with her handmade plates,

They read her writings and remember her way of living, which she expressed succinctly in one poem dedicated to her “dear friend” anger. She experienced the emotion as a powerful thunderstorm of outrage. For her, the silver lining of the tempest was how it pushed her to action. As Abbie wrote, addressing her anger directly, “I treasure your energy/ the lessons you teach/ the fiercely loving place you come from/ inside of me.”

Toward the end of her first pregnancy, a tenacious heartburn afflicted 19-year-old Abbie. To remedy the indigestion, she drank catnip tea. “They were calling me Catnip before I was even born,” her son, now 48, says. Catnip came into this world on Echo Ridge, in Idaho. His parents lived there in a commune of “less than a dozen grubby hippies,” as he recalls.

Abbie had followed two of her siblings there from Iowa City, Iowa, where she grew up as the youngest of eight kids. Her father, Manford Kuhn, died from polio when she was 10. Her mother, Agnes, was a pen pal with Eleanor Roosevelt, and one of the founders of the Iowa City Friends Meetings, a worship gathering of Quakers. “I think my mom got a lot of her salt [from Agnes in the] prim and proper, mid-60s freaking Iowa,” Catnip says.

Out west, Abbie met Bruce, who had a huge handlebar mustache and founded the first anti-war newsletter by an active-duty serviceman, in the late 60s, according to family lore. Soon after Catnip was born, the little family relocated, leaving their pet bobcat behind on the commune. After three years of rambling in Eastern Washington, Idaho, and Northwest Montana, they came to the Flathead Valley. They landed first in a farmhouse, where Eli was born in 1977, and then moved to 7 acres south of Highway 40. They lived in a mobile home with some additions, including a potting studio, and later built an affordable, cookie-cutter house on top of a hill, where Bruce’s pot patch had been, Catnip says.

They had goats and a litter or two of kittens, from the tortoise-shell calico cat named Caterpillar. They tended gardens and canned huge, steaming pots of food. Abbie saved her pottery mistakes in a big garbage can, and invited anyone who was angry to come over and smash them up. She loved spiritual tunes and old folk singers like Joan Baez, but whenever she did her fitness exercises on her mini-trampoline, she would play Van Halen’s “Jump.” The house was always messy, with laundry piles and dishes scattered about. Her mind was elsewhere.

Abbie was a founding member of the Whitefish Peace Alliance, which later became the Flathead Peace Alliance, an anti-war group. In remembrance of the devastating World War II bombing of Hiroshima, the activists set floating candles on the Whitefish River at twilight. Abbie and a friend canoed downstream to the next bend in the river to intercept the trash. In the wee hours of a cold March morning in 1985, the Alliance organized a demonstration at the Whitefish railroad depot, calling attention to a train that passed through hauling enough nuclear warheads for an explosion 1,400 times more powerful than Hiroshima. In a letter published by local newspapers, Abbie wrote that the vigil had kept “the light of hope alive” in her heart that “we’ll see an end to the nuclear insanity and find new ways to live with our sisters and brothers the world over, peacefully.”

Eli, who is now 43 and lives in Hamilton with his wife and two young sons, aged 9 and 5, sometimes tells people he grew up on the picket lines. “I grew up really admiring how empathetic she was about changing the world … I admired her strength; it was neat to watch. I also remember her getting yelled and screamed at, ‘die, hippie, die,’ in front of me,” he says. “It was confusing as a really young child, knowing about all these horrific things going on in the world, between nuclear weapons and domestic violence. That was kind of scary.” Still, he was Abbie’s little shadow, always there hanging onto her skirts while she waved her “no nukes” sign.

“Not everybody would connect domestic and sexual violence advocacy to peace and justice advocacy, and anti-war advocacy,” Shaw, the current Abbie Shelter executive director, says. “She was the beacon of progressive thought in the valley.”

Abbie bonded easily with new people, which helped her spread her word of peace. A common refrain among her people is: “She was my best friend, but she had lots of best friends.”

“She saw the good in everyone,” Dee Blank, of Whitefish, says. “Her dancing, round, light-blue eyes would stay on yours with an eager, happy smile of anticipation of whatever you might come up with. I think she charmed everybody, and we all wanted as much time with her as we could have.”

Everything about Abbie, from her anti-war convictions to her disposition, crystallized through her expression of Quakerism. “She went deep, she had a wonderfully deep spiritual dimension,” says Roger Sullivan, 70, a well-known Kalispell attorney. Abbie’s family comprised the entire Flathead Valley Quaker population at the time. In 1989, when Maria Arrington moved west from Philadelphia for the mountains, she found an “oasis” in the Frederick clan.

Arrington remembers feeling the energy of Abbie’s dancing spirit in the late 90s, when the decision to accept marriage equality for same-sex couples percolated up from the local level to the regional North Pacific Yearly Quaker Meeting. “To achieve consensus can be a real challenge,” she says, “and the pride of knowing we had held strong, and moved through every level … at the end, there was so much celebration.” The meeting was held in a college gymnasium, and Arrington felt Abbie skipping around on the top of the bleachers. When she talked to other Quakers who’d known Abbie, they said her presence was palpable for them, too.

“She was someone who danced through life, and she took serious issues by the throat,” Arrington says. “Occasionally, I’ll pull out a picture of Abbie. It just makes me smile. But more than anything, I feel her example. It became internalized by everyone who cared about her.”

Sometimes, people will ask Catnip, who now lives in Denver, Colorado, “Where did you come from? Who even made you?”

“I’m a pacifist, I’m a feminist,” he says. “Being loving and open to the world, these are qualities I’m so fortunate to have… So much of what people apparently appreciate about me, I can directly point to my mom and my dad (who passed away last year), the way I was raised, and where I was raised.” He remembers being a college-aged kid when the car hit his mom and thinking, wryly, “So, you spend 19 years bringing me up to be the person I am, teaching me to be the person I am, and then so drastically and radically forever put me to the test, proving it — thanks a lot, Mom.”

When Catnip was 18, on the last Christmas the Frederick family had with Abbie, she gifted him a notebook with a Monte Dolack painting of two pileated woodpeckers on the cover. It contained a handwritten collection of early memories of his “small self,” as she wrote, a belated effort in documentation after Catnip complained there weren’t any photos of his young childhood. It was a declaration of unconditional love, and a manifesto for his existence in the world.

Abbie described the midsummer evening after he was born, when she took him with her for a heated bath in the big wash tub in front of the fire box. “What a wonder,” she wrote. “You yawned and one of us adults caught it and yawned too and that seemed so amazing: to connect.”

She also reminisced about the time when he, at six or so months old, fell asleep at a potluck while actively eating potato salad. She gushed about what a fast-learning reader he was. She told him she began potting in part because of the ease with which she could work at the wheel while simultaneously watching him play in the backyard. In a postscript, she described the toys he had as a kid: “Funky. Homegrown.”

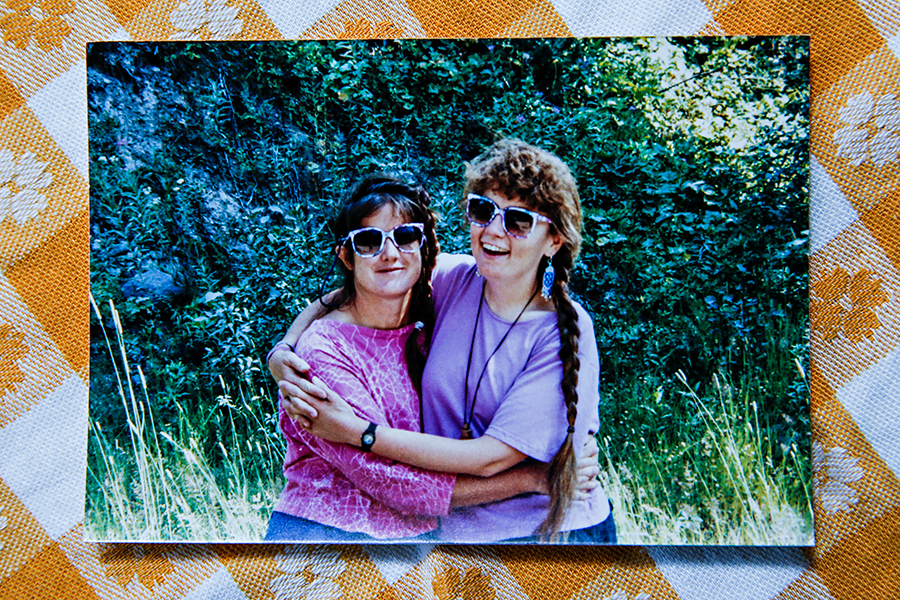

One of Paulette Lawrence’s favorite Abbie memories is from the late 80s or early 90s, when she was living in Seattle, and Abbie came to visit. “Her joy was to go to the farmer’s market,” Lawrence, 64, of Kalispell, says. One day, they went rollerblading on the waterfront. “She had this tiny little belly, her legs were skinny, she had this long, beautiful, thick hair,” Lawrence recalls. “She’s got on an old-fashioned bathing suit, her hair’s flying. She is as free as a bird … That was Abbie. She had no pretense about her.”

Just before Abbie died, Lawrence visited the Fredericks in Montana during a road trip. When she departed, Abbie dialed up Lawrence’s landline in Seattle and left a message, so it would be waiting for her friend when she got home.

“Here is what was on the message,” Lawrence says. “I don’t know if I can sing it because I’ll sob. It’s a song that she sang, not only to me, but to other people: ‘How can anyone ever tell you that you’re anything less than beautiful? How can anyone ever tell you that you’re less than whole? How can anyone fail to notice that your loving is a miracle? How deeply you’re connected to my soul.’ That was the message from Abbie, probably from the day she died, or just before. Oh, it was so profound.”

Lawrence listened to the voicemail often in the early days after Abbie’s death. She still has it, but she doesn’t know if she could bear listening to it now, all these years later. The grief still sometimes sneaks up on her, but she’s never surprised by the vividness of her pain. Her voice wobbling, she says, “I loved Abbie. I’ll love her to the day I die, and beyond.”

The Abbie Shelter’s 24-hour violence-free hotline is (406) 752-7273.