Editor’s Note: This story originally appeared in the fall 2017 edition of Flathead Living.

It’s an unassuming and largely hidden sight, the last remnant of the first local town of any great importance.

The Demersville Cemetery, tucked on the southern outskirts of Kalispell, spreads across a wide meadow scattered with giant pines and gravestones of all shapes and sizes. The old burial sites reveal the names of early settlers from the late 1800s and early 1900s: McGovern, Richards, Ingalls, Coram, Rollins. Others rest unmarked, either from time or circumstance. “Gone but not forgotten,” many say.

This quiet pasture occupies a unique place in history. It’s all there really is — publicly and in its original place — preserving the memory of Demersville, the first incorporated town in Northwest Montana.

Built around an upstart mercantile along the Flathead River 130 years ago, an 80-acre village blossomed into the region’s largest trading center and a boomtown dubbed the “new Chicago” with more than 1,500 residents. It wasn’t the first community in this corner of Montana — Ashley and other small outposts had already cropped up — but it quickly became the most successful and influential, laying the foundation for Kalispell and the modern Flathead Valley.

What began as a small community of settlers and entrepreneurs arriving on steamboats eager to build new lives in the fertile landscape proliferated into a regional destination ripe for lumber barons and railroad tycoons.

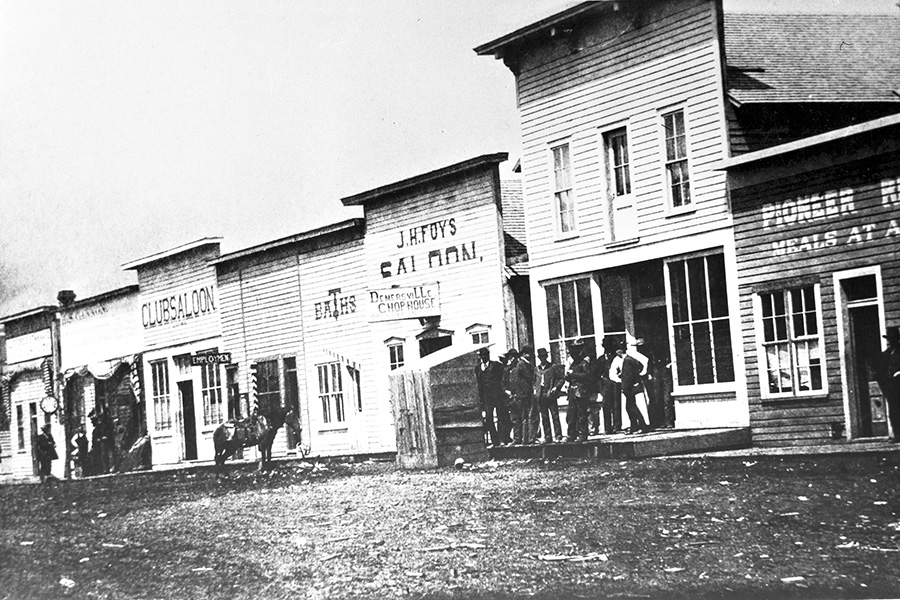

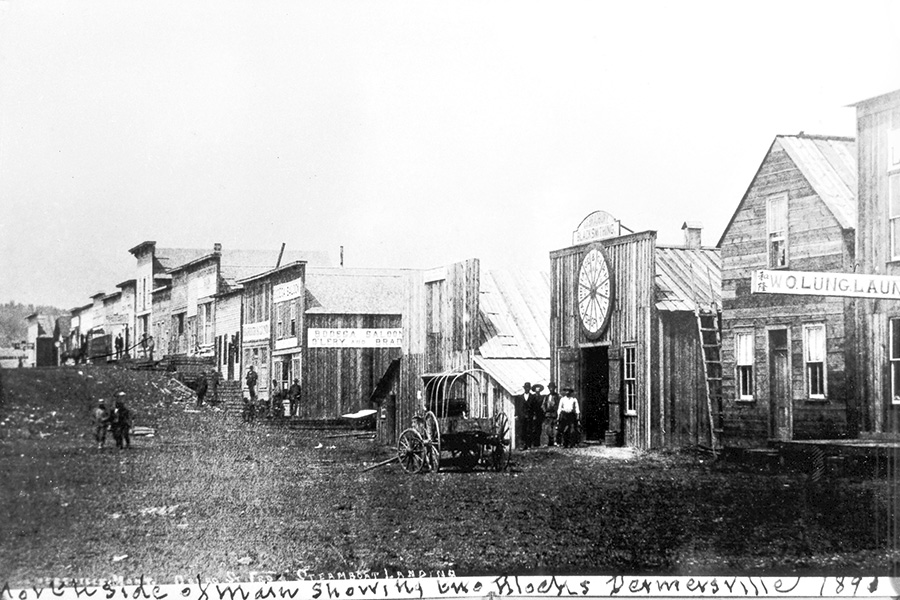

Demersville, at its peak in 1891, was home to hotels, shops, dining halls, 73 licensed liquor dispensers and numerous brothels. The July 4, 1890 edition of the upstart newspaper, founded by Demersville couple Clayton and Emma Ingalls and named the Inter Lake, applauded “the grandest celebration in the history of the Flathead Valley” as the town observed Independence Day with fireworks, music, baseball and “glass ball shooting,” as well as a dance.

The wild, isolated setting provided its share of problems, too. Homesteaders and Native American tribes that had long lived in the region struggled at times to live peacefully together. In February of 1890, to quell unrest among residents who were fearful of raiding tribes, the 25th Regiment of the U.S. Army, known as the Buffalo Soldiers, traveled from Fort Missoula with 47 black infantrymen who were stationed in Demersville. At the same time, 45 men were deputized as members of a posse that patrolled the community, sometimes infamously.

Indeed, the rapid rise of Demersville was as spectacular as it was lively. Yet the boomtown’s sudden, dramatic bust was even more remarkable as nearly everything vanished almost overnight only a few years later.

“I think it’s very unique because it’s not a ghost town. It’s a town that was physically moved to another place. I don’t know of another single example of that happening,” said Jacob Thomas, executive director of The Museum at Central School in downtown Kalispell.

“It’s a very unique story that deserves to be told.”

Telesphore Jacques DeMers was a man of bold venture.

The son of a farming family with eight kids, “Jack” was born in May of 1834 in La Prarie Parish near Montreal. He was raised Catholic and boasted an adventurous spirit at an early age. This imaginative wanderlust explains his departure in his late teens to answer the call of his era: “Go West, young man.”

Like generations of men in the middle 1800s, DeMers arrived in San Francisco with opportunity on the mind. But some 300,000 people had already beaten him to the California Gold Rush, so he ventured north into the densely forested Washington territory, where he established a homestead north of the upstart town of Spokane.

“That he was motivated, in part, to a search for wealth in these moves is certain, but he was apparently more practical and patient than to become exclusively and disastrously obsessed, as did so many, with getting rich quickly by a lucky gold strike,” the late Carle F. O’Neil, a Flathead Valley native and author, wrote in his definitive book, “Two Men of Demersville.”

DeMers tried his hand at panning and sluicing but struggled. Not to be discouraged, he tapped into another golden opportunity. The influx of miners across the Pacific Northwest created a great demand for supplies. Ever the entrepreneur, DeMers developed stores across the region stocked with trade items and other resources necessary in those days. As a well-worn traveler, he knew the lay of the land and established thoughtful routes that circulated goods without running into geographical hazards or bandits.

On June 16, 1857, DeMers married Clara Rivet, a member of the nearby Pend d’Oreille tribe, and they began building a family alongside a successful business.

A pivotal moment in the history of the entire region arrived in 1862 when the Mullan Road was completed, creating the first wagon road over the Rocky Mountains. This opened a navigable route from Fort Walla Walla through Spokane, Frenchtown and Missoula before ending at Fort Benton, encouraging greater exploration in a wild interior.

Attracted by the allure, Jack and Clara DeMers ventured into modern Northwest Montana, an area that was largely unsettled at the time except for a few outposts established by prospectors, hunters and traders, mostly French Canadian.

According to O’Neil’s book, the first evidence of DeMers’ presence in Montana was April 17, 1866, when he noted in a daybook that he visited the Hellgate Trading Post — established in the nascent town of Missoula — and purchased 21 pounds of bacon, 10 pounds of sugar, one pair of boots and potatoes for a total of $38.50.

Jack and Clara settled in the Frenchtown Valley west of Missoula, and by 1868, DeMers was buying property, investing in new commercial enterprises and cultivating his identity as a community leader. He was elected to the Missoula County Commission and served from 1875-79.

By 1879, the Missoulian newspaper reported that DeMers was the fourth-highest taxpayer in the county, paying $878. He owned mercantile stores that distributed along regular freight routes between Montana and Utah. He built a large ranching business that shipped herds of sheep and cattle as far as Texas. He operated lumber and flour mills. His business portfolio grew to include saloons, hotels and a billiard hall.

“DeMers was a man of energy, imagination and commercial daring who enjoyed the action of business development and had a natural talent for leadership and organization,” O’Neil wrote.

DeMers’ Christian kindness also made him widely beloved and elicited loyalty and respect among residents and employees. He was also a vigorous recreationist who “preferred the outdoors over the confinement of his stores, and he was often on the trail with his packers facing the same dangers and participating in the same arduous chores,” O’Neil wrote.

It was during this time that DeMers learned of a place with vast untapped potential. His stores were shipping trade goods north from Frenchtown to Fort Steele, British Columbia, where the discovery of gold was spiking settlement. Between the two areas sat a pristine stretch of land defined by a great lake and towering mountain ranges.

It was called the upper Flathead Valley.

DeMers became intrigued by this wide-open landscape. Traveling north on rugged wagon trails through tribal lands and voyaging by boat across Flathead Lake, he arrived in the sylvan valley. His original plans were to establish a mercantile in the village of Ashley, located just west of modern Kalispell. But its few residents, specifically D.J. Plume, wanted nothing to do with the newcomer, so they demanded an exorbitant price — $5,000 — for a building site, according to O’Neil.

Undeterred, DeMers picked another, more favorable location at the head of navigation on the Flathead River.

William H. “Uncle Billy” Gregg, one of the area’s original settlers, deeded DeMers a 300-square-foot section of land along the river just east of modern-day Kalispell Toyota where Lower Valley Road now runs toward U.S. 93. Gregg went on to sell DeMers a half-interest in 80 acres of surrounding land.

It was here, in 1887, where DeMers started with a tent. He filled it with merchandise and brought up trusted employees from Frenchtown to protect everything while DeMers traveled back and forth, devising a vision for his upstart community.

Sometimes timing is everything, and DeMers lucked out. The Montana Territory was rapidly growing with homesteaders as the prospect of statehood loomed on the horizon. The 1880 census tallied only 27 non-native people living in the upper Flathead Valley, according to state historical records, but that number spiked as settlers arrived to explore the uncertain yet attractive opportunities awaiting them at the northern end of Flathead Lake.

And it just so happened that there was a new town along the Flathead River with all the suitable amenities and attractions.

The influx meant DeMers needed additional help from trustworthy and educated men, so he hired George Francis Stannard and John E. Clifford, who would later become his son-in-law, to oversee his new mercantile, which grew from a tent into a large log building by 1888. DeMers began investing heavily in other businesses, including a large hotel that he named “Cliff House” in honor of Clifford.

In 1889, there were fewer than a dozen buildings in Demersville, but within one year, there were 50 lining the dozen streets that spread far and wide. The community’s impressive growth included a town hall, jail, several stores and hotels, a race track, two churches — Methodist and Catholic — and, as to be expected in the Old West, 73 saloons.

“Mushroom town springs up over night and there is great excitement we might become a second Chicago or St. Paul,” the Inter Lake proclaimed July 21, 1889. “Outsiders come by the hundreds. The stage line can not haul them all from Ravalli to the lake, so the freight teamsters come to their help and haul them by four-horse wagon loads.”

The 1890 census now showed more than 3,000 non-native people in the Flathead, and at least half lived in the vibrant community unofficially known as Demersville.

Ranching and farming were the primary lifestyles of choice, but logging developed into an especially lucrative enterprise, and lumbermen arrived in droves.

“Demersville truly was a rough-and-tumble boomtown, with trappers, prospectors, lumberjacks, freighters, and traders flowing in and out, trying to profit from the Flathead’s abundant resources or from each other,” Kathryn L. McKay wrote in her book, “Montana Main Streets: A Guide to Historic Kalispell.”

It was around this time when another major entrepreneur showed up in the Flathead.

James J. Hill, the railroad tycoon who owned the Great Northern Railway, was interested in expanding his empire through the Pacific Northwest, a passageway that would grow ridership and tap into rich commercial prospects, primarily timber.

Hill began extending the railroad from St. Paul, Minnesota to Seattle, and the route he selected proved pivotal for communities that were either positioned favorably along the line or not. Great Northern kept its exact plans secret as it began scouting land, and towns such as Demersville, Ashley and the new community of Columbia Falls tried courting Hill for selection as a division point between Cut Bank and Troy.

“The stakes were high and the competition fierce,” McKay wrote.

This is where history arrives at one of those decisive “What if?” moments. As Hill was preparing to choose the destiny of his great railroad — and the fate of future growth in the Flathead — Jack DeMers was dying. By 1889, his health had declined rapidly due to Bright’s disease, a type of kidney disease that was also accompanied by heart problems.

While riding a train to Salt Lake City, DeMers was removed for medical care and sent to a hospital in Butte, where he died on May 18, 1889, exactly one week after his 55th birthday. Newspaper accounts across the state quickly spread the news: “the deceased being one of the oldest and best known men in the county,” the Missoulian wrote.

DeMers’ absence from his namesake town was significant for several reasons. For starters, as the primary investor in the town’s initial growth, he had taken on sizable debt. Clifford, who had married DeMers’ daughter Delima, was the heir apparent — both financially and logistically — but was notoriously extravagant in his spending and ill-equipped to oversee a suite of businesses as diligently as his father-in-law.

Secondly, and perhaps most importantly, DeMers and his outsized personality were absent as Hill was deciding where to build his rail line in the Flathead Valley.

“It is possible … that had T.J. lived his influence would have been great enough with James Hill that the latter’s Great Northern might have been routed through Demersville in a juncture of rail and water transportation thereby obviating the development of Kalispell,” O’Neil wrote.

“But, of course, we will never know.”

Demersville was denied. Geographically, its location was challenging for a prospective rail line that would have to navigate the winding nature of the river and detour significantly south from its entrance into the valley from Marias Pass. But another, likely more significant factor came into play.

“Money talks, and there was more land available in Kalispell than there was in Demersville,” said Thomas with The Museum at Central School. “James Hill and his buddies bought a lot of land that would become Kalispell. And (Charles Conrad) was one of them.”

Hill tasked his friend Conrad, a successful businessman with a similar entrepreneurial spirit as DeMers, to acquire the proper land needed for a new railroad division point. Instead of the most populated center in the valley, Conrad rebuffed Demersville and purchased a large swath of hay meadow owned by Reverend George McVey Fisher about 3.5 miles to the northwest.

Newspapers across the state announced the historic moment on March 17, 1891: the townsite of Kalispell was formally established and would serve as the Great Northern Railway’s division point.

The future of the Flathead Valley was decided by the placement of railroad stakes. Demersville seemed like it would still have a stake in the game one way or another; maybe a spur line would dart south from Kalispell. Something would eventually work out for the largest town in the valley, right?

“Flathead valley promises to be an exceedingly lively locality this summer, and Demersville being the only town of any great importance there at present, the merchants and businessmen of that town will reap the benefit,” the Great Falls Tribune declared in the spring of 1891. “When the Great Northern is completed through the valley and the Northern Pacific branch reaches Demersville there will probably be a great rivalry developed between the various towns in the valley, but the adjacent country is rich and productive enough to support several good towns.”

As time would tell, the new town to the north would prove to be less of a rival and more of a death knell to its predecessor.

Chalk it up to Clifford’s reckless nature or the inevitable, but the arrival of Kalispell marked the end of Demersville. Clifford was elected as the town’s first, last and only mayor in 1891, the same year the town was officially incorporated. The boisterous mayor, ignoring the threat that Kalispell posed, declared in a quote to the Helena newspaper, “The people of (Demersville) are preparing for the construction of railways and a season of genuine prosperity,” according to O’Neil’s book.

Indeed, it was a great town and a great time. Clifford may have seemed logical in his assumption it would survive and thrive in spite of Kalispell. After all, this was still the place to be. Frank Linderman, the famed writer and politician, met his future wife Minnie in Demersville. Word of local festivities spread across the state. Many of the valley’s great names — Foys, Coram, Ingalls — all lived here. All of the railroad supplies — and workers — necessary to build Kalispell needed the river town. Workers from across the West, including a large contingent of Japanese and Chinese, flooded the valley, which expanded with Whitefish and other communities near Glacier National Park, as well as modern Lincoln County.

“The grand irony is that Demersville is where all the railroad workers stayed and lived and spent their money while they built the railroad in Kalispell,” Thomas said. “All the parts went through Demersville only to leave it all behind soon after.”

It was the beginning of the end for Demersville. In many ways, the town rotted from the inside while falling apart on the outside. Frequent fights, robberies and even murders plagued the raucous community. Without a fire department, blazes were a frequent problem, and one incident leveled more than 12 buildings in 1891.

Investors and businesses were drawn north along with everyday families who considered Kalispell’s prospects better suited for success and safety than Demersville, where rowdies frequently took perch atop storefronts and drunks teetered at the roofline, and “descriptions of conflagrations bordered on the comical,” the Inter Lake reported in a retrospective in April of 1976.

In only a matter of months, in the winter of 1892-93, Demersville disappeared. Piece by piece, the once-prosperous town packed up and moved to Kalispell, where Conrad’s benevolence and orderly townsite attracted the masses, similar to Demersville once upon a time. A few residents stayed behind, the last vestiges of a boomtown.

“Building after building, some even with people inside, were moved across the slightly rolling land between the cat-tailed marshes from Demersville to Kalispell,” O’Neil wrote.

“The bank, the indomitable newspaper, stores, bars, cafes, the Methodist church (the Catholic church was torn down, the bricks salvaged) and countless houses were jacked up, set on skids or rollers and tugged away.”

And like a dream or a leaf in the river, Demersville was gone.