Anticipation and Anxiety as Class Resumes

Schools enter the fall semester as flashpoints in a broader COVID-19 cultural debate, with education officials confronting complicated social dynamics and laws that contradict public-health guidance

By Myers Reece

Micah Hill was feeling good when summer started.

A difficult school year, his first as Kalispell Public Schools superintendent, was in the rearview mirror. The community mood was jubilant, events were coming back and the rolling average of new novel coronavirus cases in Flathead County the last two weeks of June was merely six per day.

One month later, COVID-19 cases were skyrocketing, hospitals were filling up and the pathway to a straightforward school year was suddenly riddled with complicated obstacles. Exhaustion over public-health precautions such as masks was widespread, manifesting itself as even more entrenched opposition. Changes in state leadership, as well as legislation, cultivated a more hands-off approach to coronavirus public health.

Hill, a proponent of face coverings who credits them as a major reason his district was the only one in AA to avoid school closures last year, knew the environment was inhospitable for a mask mandate in schools, a sentiment shared by even the district’s COVID-19 advisory council made up of medical professionals.

In a letter to KPS, the advisory council recommended face coverings as “the safest way to proceed into the new school year,” with the caveat: “However, we recognize that taking into account the current community and state climate likely makes a mask mandate controversial and difficult to require.”

Still, Hill and other superintendents, as well as public-health officials, had one other good tool at their disposal in fighting COVID-19: a system of quarantining unvaccinated close contacts of identified positive cases, which the entire country uses in adherence to guidelines from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).

But then Hill received word from the governor’s office informing him that House Bill 702, passed during the last legislative session to prohibit discrimination based on vaccine status, disallowed the specific quarantining of unvaccinated people, in direct contradiction of CDC guidance and national public-health norms.

The choice was now stark: don’t quarantine anybody and risk allowing the virus to spread freely, or quarantine all close contacts, even the vaccinated asymptomatic, and risk clearing out schools quickly.

“It’s a game changer,” Hill said, noting that schools quarantine unvaccinated close contacts of measles and whooping cough cases but now can’t do the same with COVID-19.

Faced with those options, a number of Montana county health departments, including in Flathead County, have reluctantly abolished mandatory quarantining while instead adopting a recommendation system, walking a tightrope of abiding by state law while still trying to promote CDC public-health science.

All identified close contacts in Flathead County will now receive letters that advise, not require, them to quarantine for 10 days if symptom-free on the 11th day. The quarantine period may be shortened to seven days if the person receives a laboratory-tested negative result five or more days after exposure and has no symptoms by the seventh day.

The quarantine guidelines note that anybody with a lab-identified COVID-19 detection in the last 90 days is exempt regardless of vaccination status, while also providing a paragraph about CDC guidance that states “quarantine is not necessary unless you develop symptoms associated with COVID-19 illness.”

Joe Russell, the county’s health officer, said the revised quarantine approach applies to everybody in the county, but he rolled it out with schools firmly in mind.

“Our primary goal is to try to keep the schools open,” Russell said. “There are so many aspects to public health, and when we closed the schools before, it devastated commerce, it devastated our businesses. We’re doing what we can to keep businesses open in Flathead County by keeping parents at work and not at home tending to their children.”

In encouraging people to follow the quarantine guidelines, Russell uses the language of personal responsibility.

“Personal responsibility gets thrown at me a lot,” Russell said. “I’m saying here people need to be personally responsible. I’m asking people to make a good personal choice not to make other people sick.”

House Bill 702, part of a slate of Republican-sponsored bills that chipped away at local authorities’ ability to implement public-health measures, initially received attention for prohibiting employers, including hospitals, from requiring vaccines, making Montana the only state in the country to wholesale disallow vaccine mandates. The president of the Montana Medical Association called the bill a “travesty” that goes “against everything we’ve ever known or believed about public health.”

But as schools are reopening for fall, the legislation’s impact on quarantines is now taking center stage.

In response to the bill, health officials in major counties such as Flathead, Lewis and Clark, Silver Bow, Cascade and Gallatin are no longer issuing quarantine orders, while Missoula County has opted to continue following CDC guidance even at the risk of violating state law. According to the Associated Press, the state Department of Justice and governor’s office said it was up to county attorneys to interpret state law.

“It seems extreme to me that state law would prohibit us from following CDC guidance,” Anna Conley, a deputy county attorney with the Missoula County Attorney’s Office, told the AP.

While vaccines for diseases such as whooping cough and measles are mandated in schools, with exemptions, the COVID-19 vaccine is treated much like the flu shot: recommended but not required. Public health officials, as well as state leaders such as Gov. Greg Gianforte, highly encourage vaccination for all eligible ages.

The youngest eligible age group, 12-17, had a 27% first-dose administration rate in Flathead County as of Aug. 20. Children under age 12 have not yet been authorized to receive the shot, which factored into the Whitefish School District’s decision to require masks for kindergarten through sixth grade. The mandate has prompted public protests.

Russell, the county’s health officer, echoes the consensus of leading state and national medical experts in touting the efficacy of vaccines. While breakthrough cases have been occurring locally and across the country, unvaccinated people still make up more than 90% of hospitalizations and deaths.

“I’m tired of hearing stories about people in a bad way or on their death bed in the hospital saying, ‘I wish I would have gotten the COVID vaccine,’” Russell said. “It’s way too late. It’s really frustrating at times in public health. We think we’re sending the right messages out there but it’s not getting to everyone.”

One of Russell’s frustrations is hearing misinformation that often contributes to anti-vaccine and anti-mask fervor, as well as unnecessary deaths and strain on the healthcare system.

“I believe in public-health science,” Russell said. “When I hear that the vaccine is killing people, it’s a blatant lie. It’s trying to make people afraid of getting the vaccine. It’s killed literally no one in the U.S. The science says vaccines work.”

The only other Flathead County district to mandate masks is Somers-Lakeside, which responded to the local COVID-19 surge by switching from strongly recommending to requiring masks in K-8 for the first six weeks of the school year.

In an Aug. 24 letter explaining his decision to recommend the mandate, which the board approved 5-2, Superintendent Joe Price noted that the county recently set a pandemic single-day record of COVID-19 hospitalizations. Furthermore, he said the explosion in cases among the broader population has led to more pediatric cases, including 168 since July 1, with 96 among children between the ages of 4 and 11.

Price said in an interview that the district has received a handful of supportive messages, but most of the feedback has been in opposition to the mandate.

“People are very upset; people are very angry,” Price said. “But when I make a recommendation, it’s not based on a majority vote. It’s based on what I know and what I can learn from other sources. I knew it wouldn’t be popular, but I knew it was right.”

“When you look at what the medical experts are telling us,” he added, “they’re all saying we should wear masks in school. It’s very difficult to advise my board to go against that recommendation.”

On Aug. 31, the Gianforte administration issued an emergency rule stipulating that school districts “should consider, and be able to demonstrate consideration of, parental concerns when adopting a mask mandate.” Gianforte said “arbitrary” mask mandates are “based on inconclusive research that fails to prove masks’ effectiveness in reducing the incidence of COVID-19 in the classroom.”

“Montana students deserve to be back in their classroom in as normal and safe an environment as possible,” the governor said. “Montana parents deserve to know their voices are heard in schools when health-related mandates for their children are being considered. They also deserve to know that schools are reviewing reliable data and scientific research about the impacts of mask mandates on students.”

It wasn’t immediately clear how the rule might impact local districts, but the Missoula County Public Schools district, which has a mask requirement in place, issued a response stating that it believes its mandate holds up, as the district both considered parental concerns and provided an opt-out system for certain reasons.

“The District will continue to enforce its face covering guidelines to ensure the safety and welfare of all students and staff,” the statement continued.

Price said face coverings were instrumental in the district’s ability to provide in-person instruction every school day last year, and he wants to see a no-closure repeat this year.

“If masks make that more likely, that’s a tool I want to use,” he said.

But he noted that House Bill 702 takes away the “very important tool” of mandatory quarantines.

“What it means in schools is that it increases the chances of transmission significantly,” he said. “If we have people who should be in quarantine coming into our schools — and you can be asymptomatic for a couple days — they might be positive and can spread it but don’t feel sick yet. That’s a dangerous thing.”

The combination of legislation and the state’s generally more relaxed approach to COVID-19 protocols than under former Gov. Steve Bullock, including no statewide mask mandate, has left school boards and superintendents in the position of considering precautions that are sure to cause backlash without the benefit of state support.

The state’s top education official, Republican Elsie Arntzen, recently joined a protest in opposition to the Billings School District’s mask mandate, which was implemented following an outbreak within an extracurricular activity at a high school.

“If you look at the political will of the state from the governor to the office of public instruction to legislators, the laws that were passed, it’s pretty clear that whatever is in place is meant to prevent districts from taking action,” Hill, the Kalispell superintendent, said, adding later in a letter to families and staff that the district is confronting “legislation and communication from our top state officials that are counter to the recommendations and guidance given by our health care system and public health authorities.”

Hill described the daunting proposition of recommending a mask mandate in a community where businesses aren’t broadly requiring face coverings and majority public sentiment appears to lean toward opposition. Hill feels that a mandate would “put the school district back in the middle of that political divide,” and would be largely untenable without broader community support.

“Schools — where we are charged with not only educating our community’s children but asked to do so in a safe environment — have somehow become a flashpoint in this conversation,” Hill wrote to families and staff on Aug. 25. “At times, it feels like we are in an impossible position.”

“The polarization within our community has been wearing on everyone,” he continued. “The constant conflict and struggle that comes with enforcing a mask mandate significantly diminishes our educators and administrators’ ability to focus on what they do best. This is not something we take lightly. We strongly believe that our students deserve more than ongoing conflict and tension.”

Districts are trying to avoid the widespread closures seen in other states where school started weeks ago, while also hoping not to experience the rising pediatric hospitalizations in states such as Texas, which are often the result of coinfection with another pathogen such as RSV.

Hill said school districts, including KPS, will have access to a grant to pay for rapid COVID-19 tests, which will be made available at all Kalispell school sites. Also, due to the changes in isolation and quarantine protocols, “and the impact this has on our teaching staff and students,” KPS has shifted its schedule to implement early release every Wednesday to give the district more flexibility.

The district also holds out the possibility of implementing a mask mandate “if we digress to a point of risking school closure,” according to Hill’s letter.

Russell has been in regular communication with school administrators as the fall semester gets underway, with some districts, including Whitefish and Columbia Falls, kicking off last week and others beginning either this week or next. Russell said “only time will tell” how the return to school shakes out.

“I think we have a lot of very outstanding school superintendents in Flathead County,” Russell said. “None of them are taking this lightly. I also don’t believe they’re afraid. There may be some trepidation with the uncertainty going into the year. There are so many unknowns.”

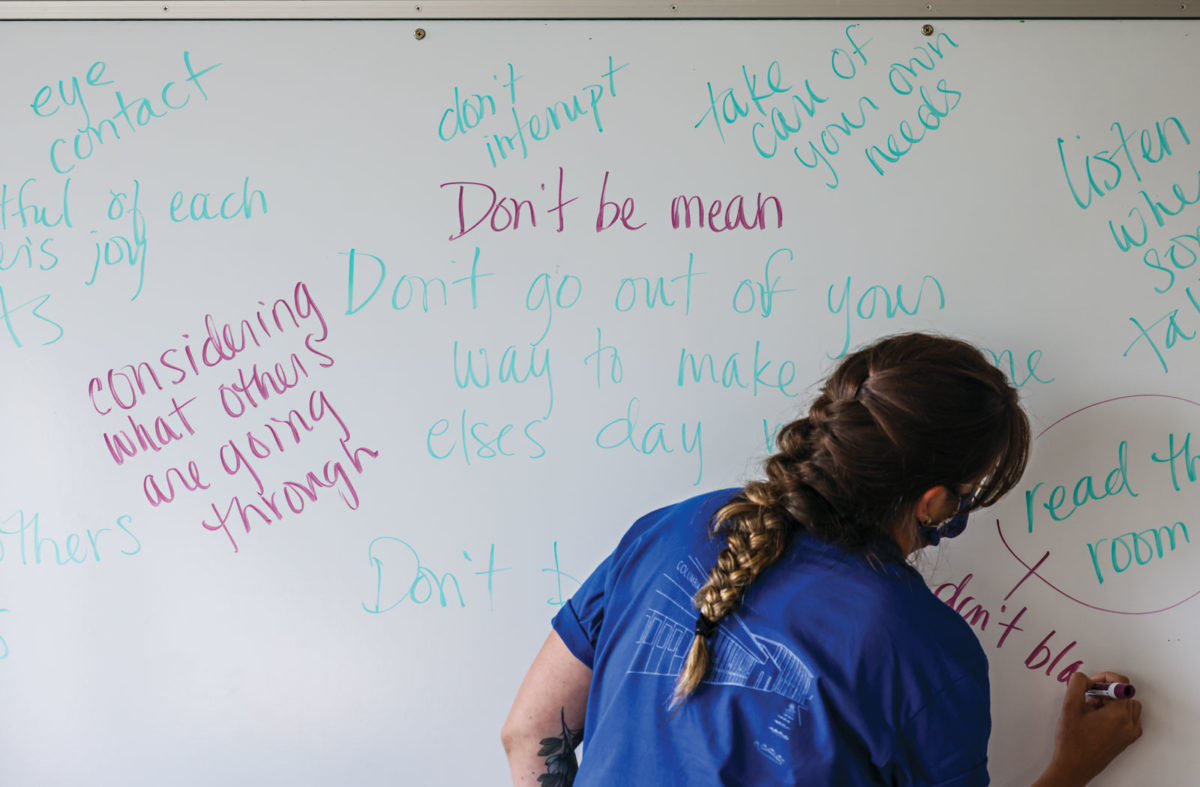

As school boards, administrators and staff navigate their unenviable role as flashpoints in a broader cultural debate, they are also doubling down on what they do best: educating the next generation. Price, the Somers-Lakeside superintendent, said his district’s elementary teachers recently participated in three days of professional development training.

“People are definitely committed to doing the best they can,” he said. “A new year is always fun. It’s great to come back every fall. The kids are excited. The teachers are enthusiastic.”

As for Price?

“I’m excited but anxious.”